In this newest series, I am going to be bringing forward research I have done in the past, as well as new research, on the Great Lakes region of North America.

In the first part of the series, I looked at cities and places all around the shore of Lake Superior, starting and ending in the Thunder Bay District of Ontario, with particular attention to lighthouses; railroad and streetcar history; waterfalls, wetlands and dunes; interstates and highways; major corporate players; mines and mining; labor relations; and many other things.

In the second-part of this series, I am going to be taking a close look at Lake Michigan, where I expect to see more of exactly the same kinds of things seen in the trip around Lake Superior.

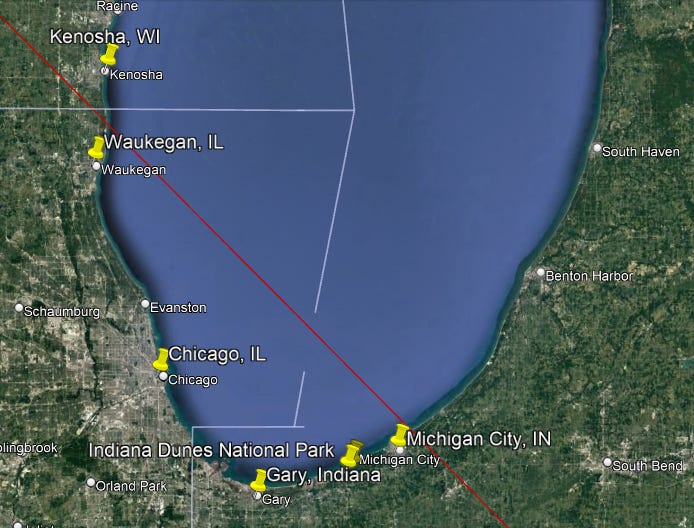

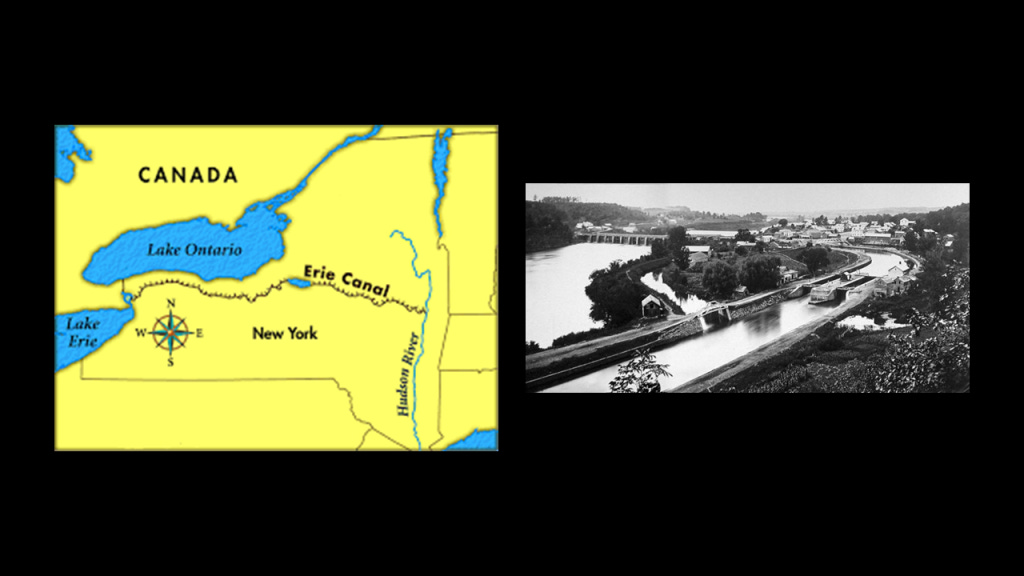

Lake Michigan is the only one of the five Great Lakes that lies entirely within the United States.

Those states are Michigan, Indiana, Illinois and Wisconsin.

By area, it is the world’s largest lake in one country.

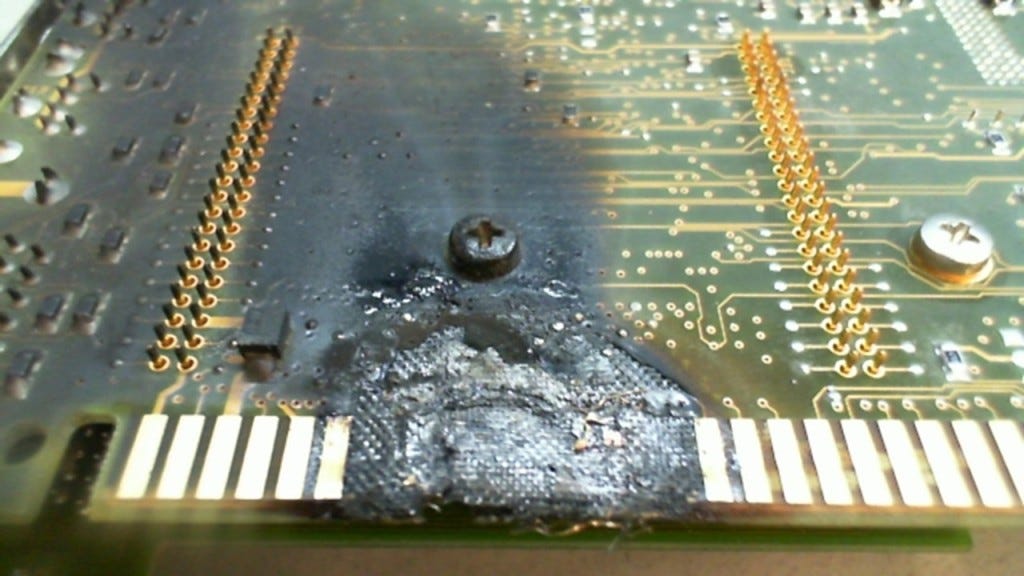

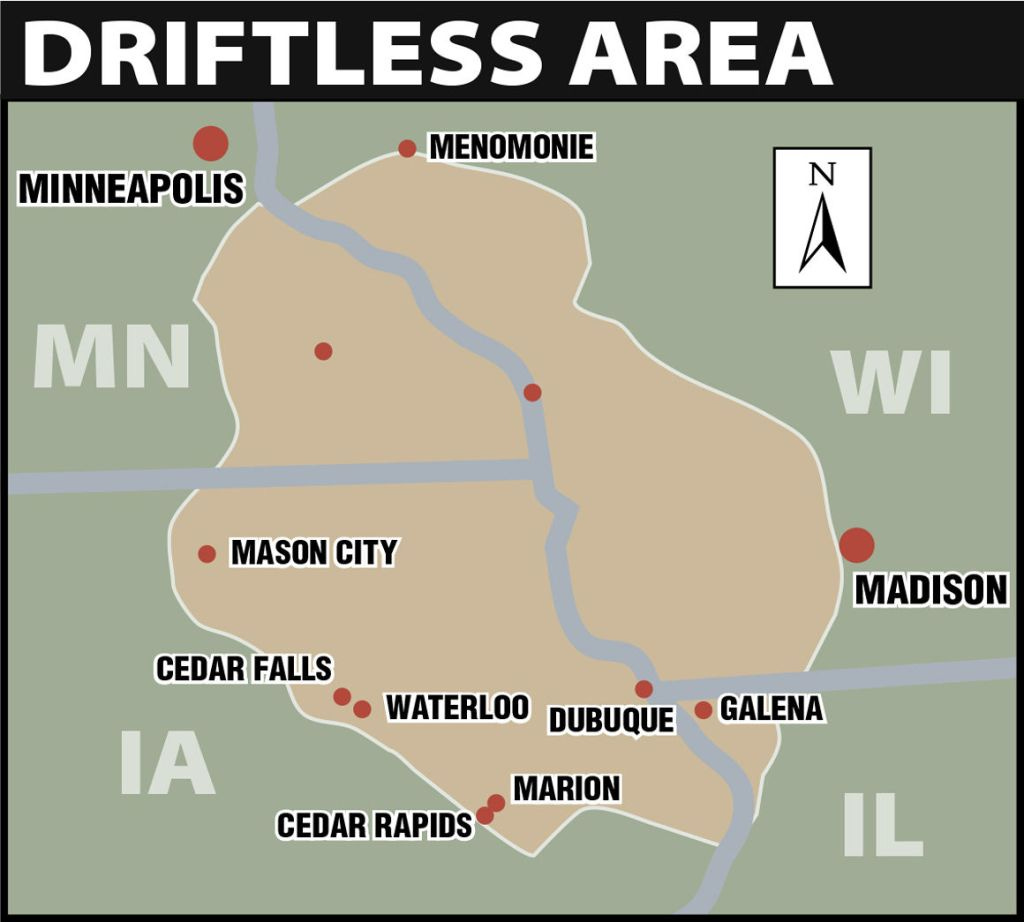

My working hypothesis is that the circuit board of the Earth’s original energy grid system was deliberately blown out by one or more forms of directed frequency or energy of some kind into different places on the Earth’s grid, causing the surface of the Earth to undulate and buckle.

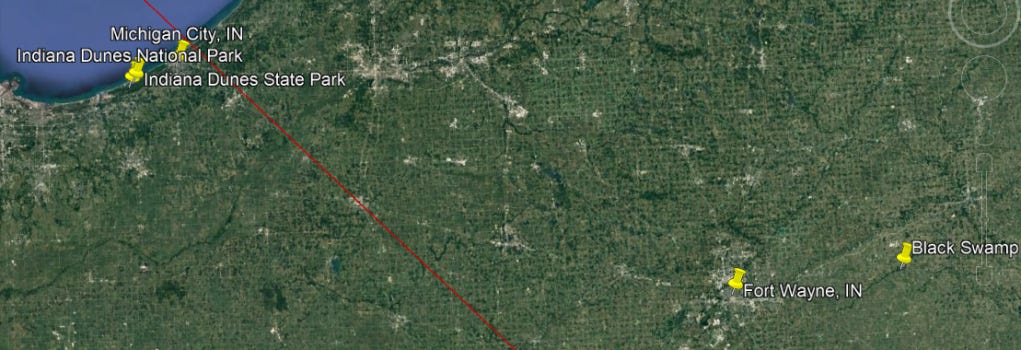

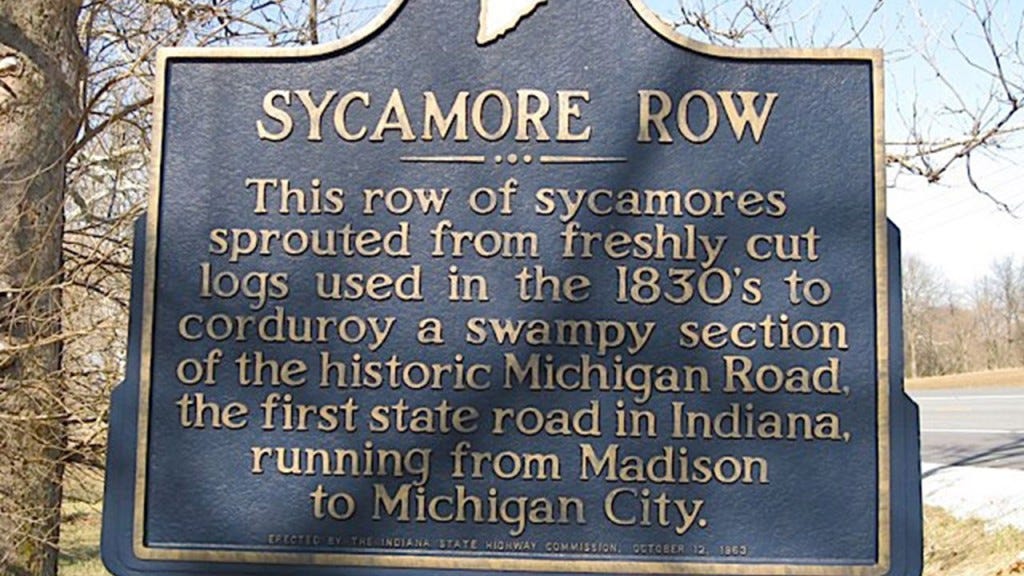

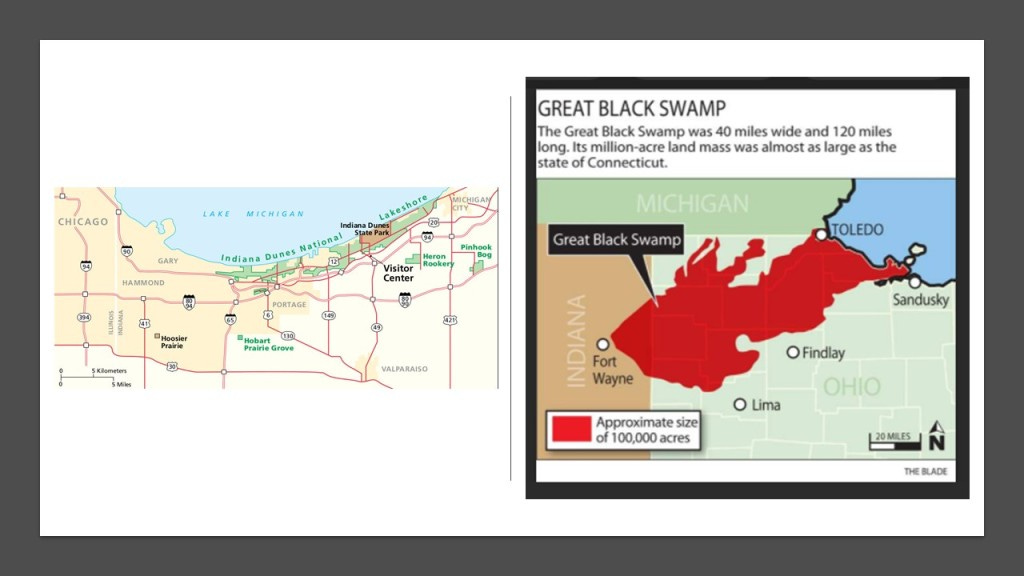

Firstly, what I am seeing from tracking leylines all over the Earth, looking from place-to-place at cities in alignment over long-distances, are the consistent presence of swamps, marshes, bogs, deserts, dunes, and places where it appears land masses sheared-off and submerged under the bodies of water we see today.

Secondly, I believe the beings behind the cataclysm were shovel-ready to dig enough of the original infrastructure out of the ruined Earth so they could be used and civilization restarted, which I think started in earnest in the mid-to-late 1700s and early 1800s.

There’s extensive underground infrastructure where people could have survived until the surface of the Earth was habitable.

Then they only used the pre-existing infrastructure until they found replacement fuel sources that could be monetized and controlled by them for what had originally been a free-energy power grid and transportation system worldwide, and when what remained of the original infrastructure was no longer useful to them, or inconvenient to their agenda, they had it destroyed, discontinued, or abandoned, typically in a very short time after it was said to have been constructed.

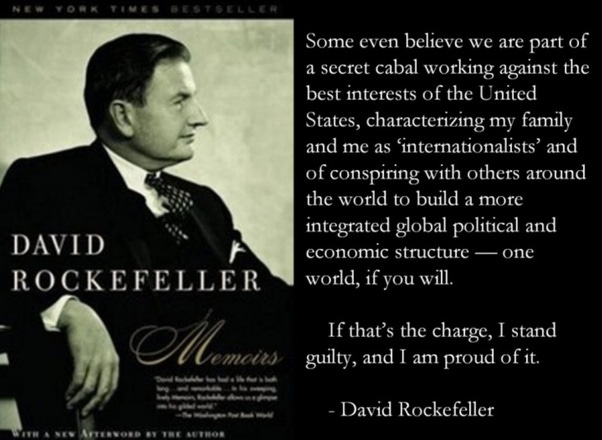

While the new elite class lived in the lap of luxury, and helped themselves to the best of everything, they had little care for anyone or anything else.

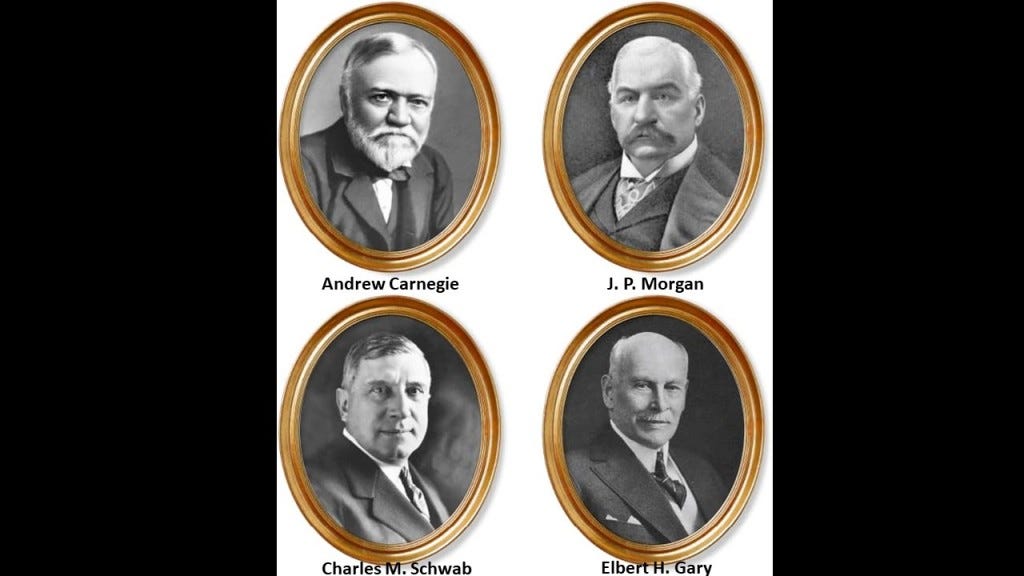

The same story repeats all over the country with the Robber Barons coming in and setting up shop and taking control of everything, and the Great Lakes region is no exception to this pattern, and if anything, actually exemplifies it.

Like everything else we have been told to explain what is in existence in our world, I don’t believe lighthouses were built to guide ships by whom they were said to have built them when they were said to have been built.

What I am seeing is that they ended up next to the edge of water when the land around them sank, and were repurposed into navigational aids in the New World to guide ships through the now broken landmasses in the surrounding waters.

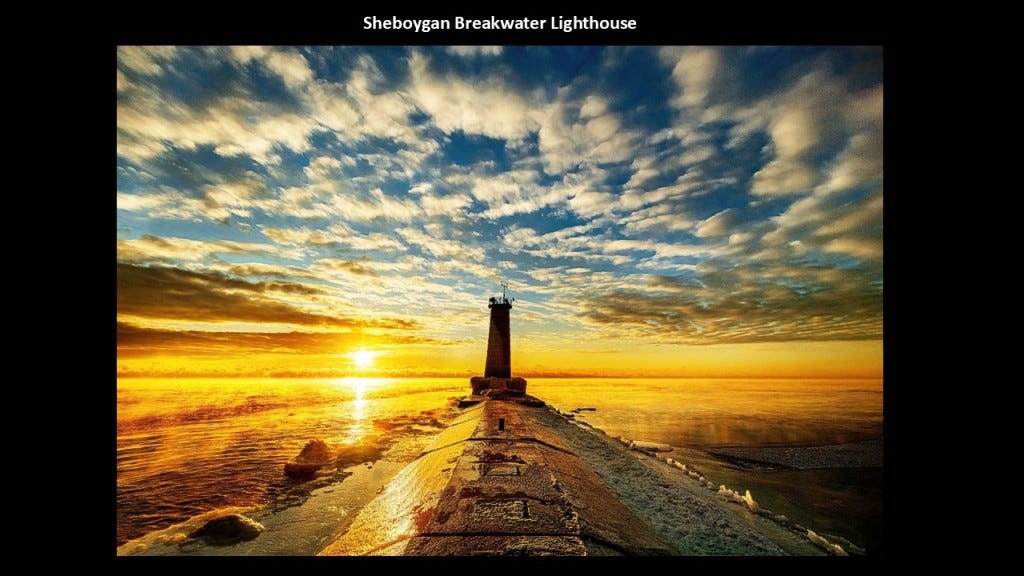

So two of the many points of comparison between Lake Michigan and Lake Superior in this post will include lighthouses, and the bathymetry of the lakes, which is the measurement of the depth of water in the lakes.

First, a comparison of the number of lighthouses between the two.

There are approximately 88 lighthouses along the shore of Lake Michigan, which has more lighthouses than any of the Great Lakes.

There are approximately 78 lighthouses around Lake Superior, with 42 of them being in Michigan.

Next, bathymetry, or the measurement of the depth of water in the lakes

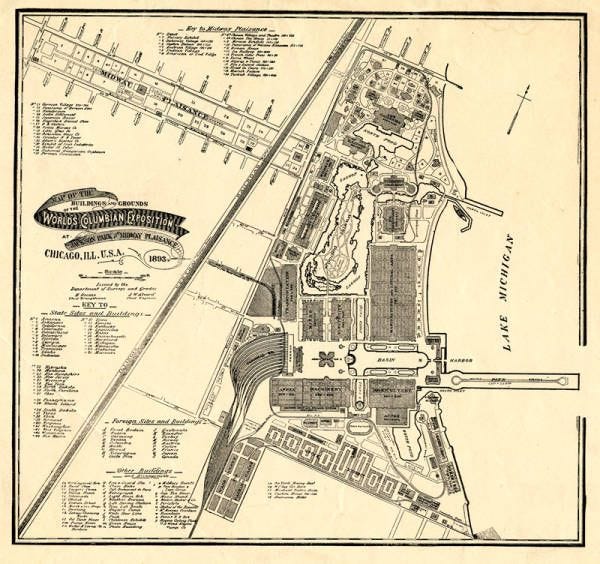

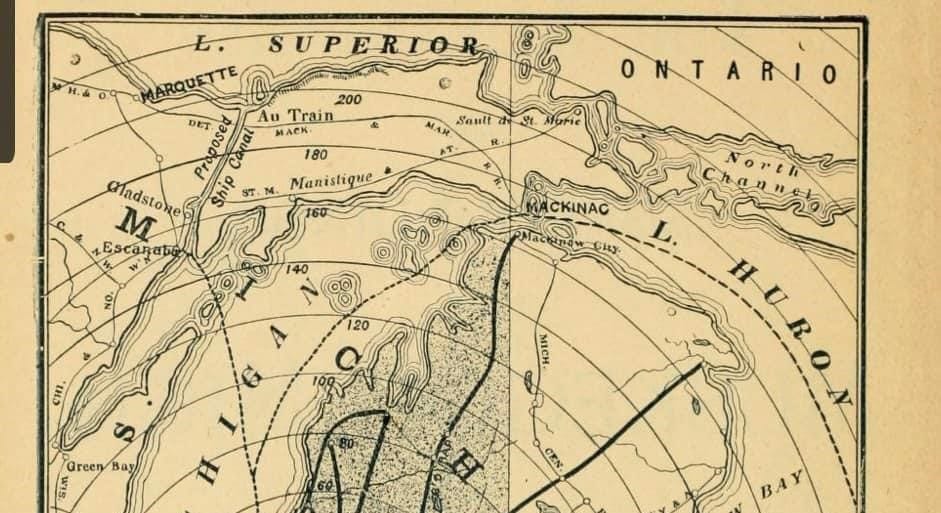

First, the bathymetry of the waters of Lake Michigan.

The bathymetry of Lake Michigan shows shallows around the edges ranging from 0 to around 100-meters, or 0- to around 328-feet, with an uneven lake-floor towards the middle ranging in depth from 100-meters, to its deepest point at 282-meters, or 925-feet, which is marked by the “x” circled in red.

The average depth of Lake Michigan is 85-meters, or 279-feet.

Here’s a breakdown of the five regions of this lake’s bathymetry: Islands and Straits; Green Bay; the Chippewa Basin; the Mid-Lake Plateau; and the South Chippewa Basin.

The Islands and Straits region of Lake Michigan includes the Mackinac Channel; the Strait of Mackinac between Lake Michigan and Lake Huron; Sturgeon Bay; St. Martin Bay; Grand Traverse Bay; and several islands of varying sizes including Beaver Island, the largest island in Lake Michigan

Most of the northern section of this region in the Mackinac Channel and Strait, Sturgeon Bay and St. Martin Bay, is quite shallow, ranging in depth from 0- to 50-meters, or 0- to -164-feet, with deeper depths of up to 200-meters, or 656-feet, seen closer to shore mixed in the with shallows, on the northeastern section which includes Grand Traverse Bay and the Manitou Passage.

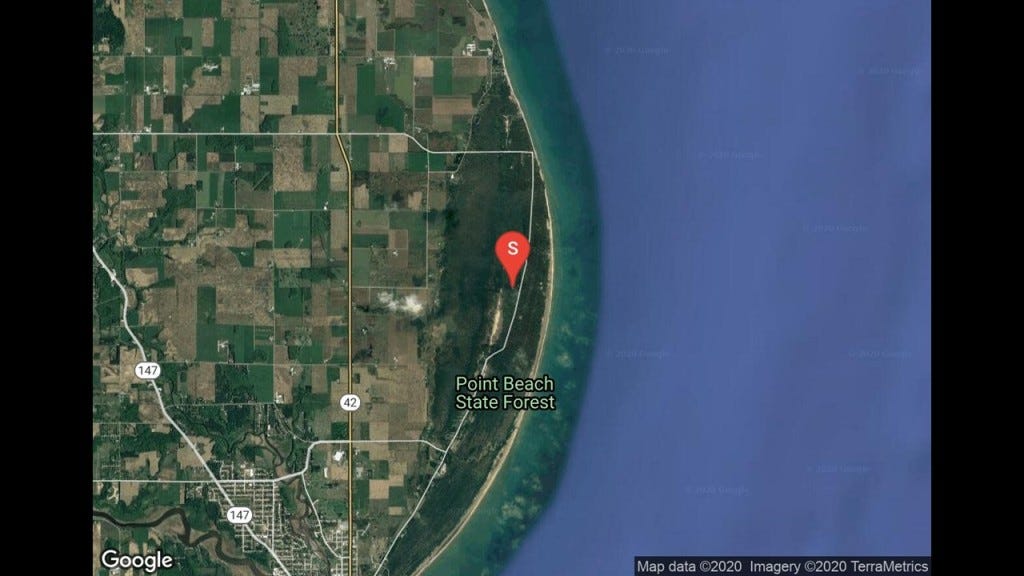

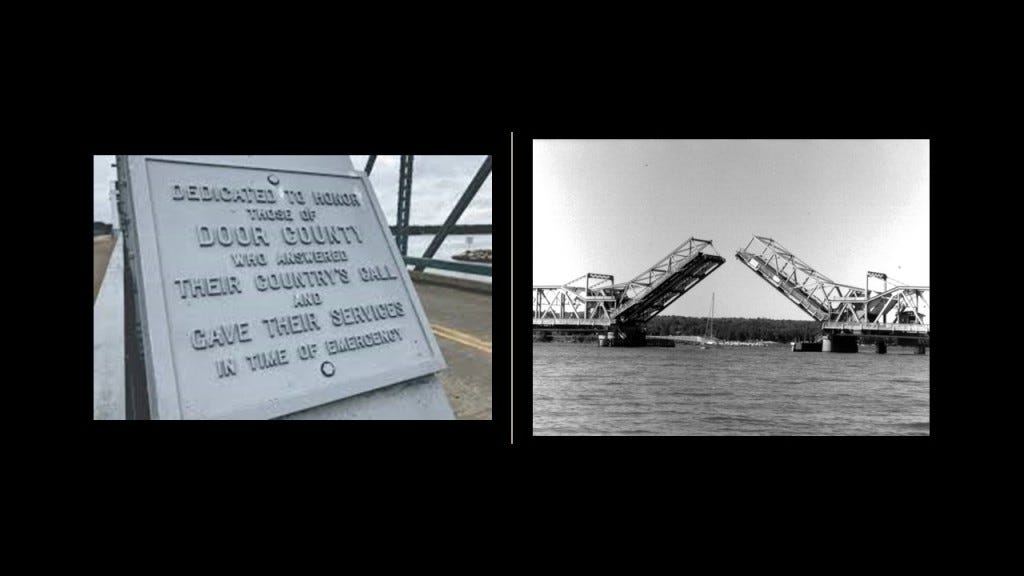

Likewise, the Green Bay region on the Wisconsin-side of Lake Michigan, which includes some other bays, channels and islands, as well as the Door Peninsula separating it from the main part of the lake, are also quite shallow, ranging in depth from 0- to around -50-meters, or 0- to -164-feet.

The Chippewa Basin roughly in the north-middle of Lake Michigan, is the deepest, with depths primarily ranging from 100-meters, or 328-feet, to its deepest point at 282-meters, or 925-feet, as previously-mentioned.

The Mid-Lake Plateau region is located in the center of Lake Michigan between the Chippewa Basin and South Chippewa Basin.

The Mid-Lake Plateau is showing as 50- to 100-meters, or 164- to 328-feet, in-depth.

Directly to the west of the Mid-Lake Plateau is the Milwaukee Basin, and directly to the east the Muskegon Basin, with both of these basins somewhere around 150-meters, or 492-feet, in-depth at its deepest.

Lastly, the South Chippewa Basin is also approximately 150-meters, or 492-feet, in-depth, at its deepest.

The bathymetry of Lake Superior also shows its shallows around the edges, which range from 0 to around 100-meters, or 0- to around 328-feet, with an uneven lake-floor ranging in depth from 100-meters, to its deepest point at 406-meters, or 1,333-feet.

Lake Superior’s average depth is 147-meters, or 483-feet

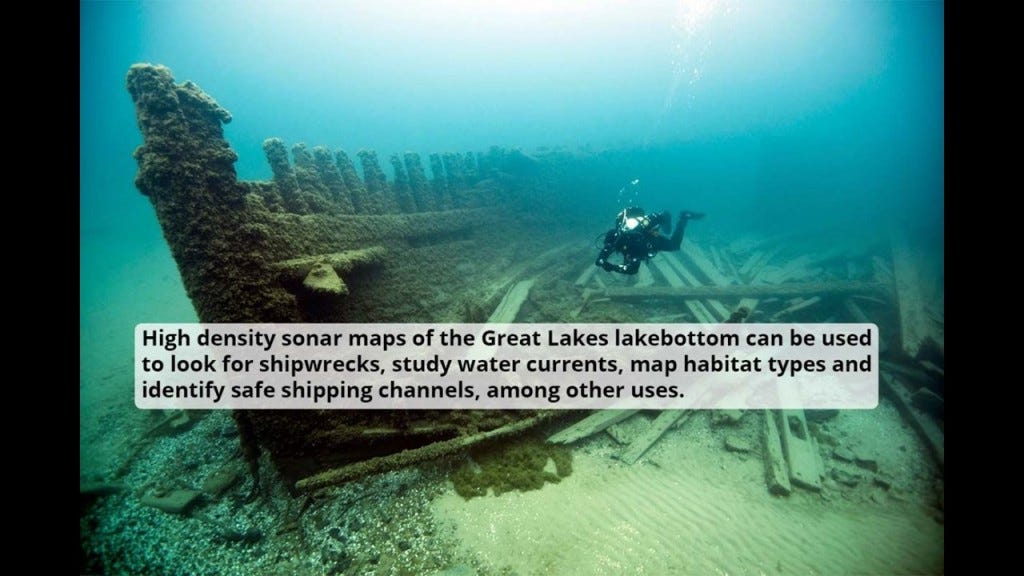

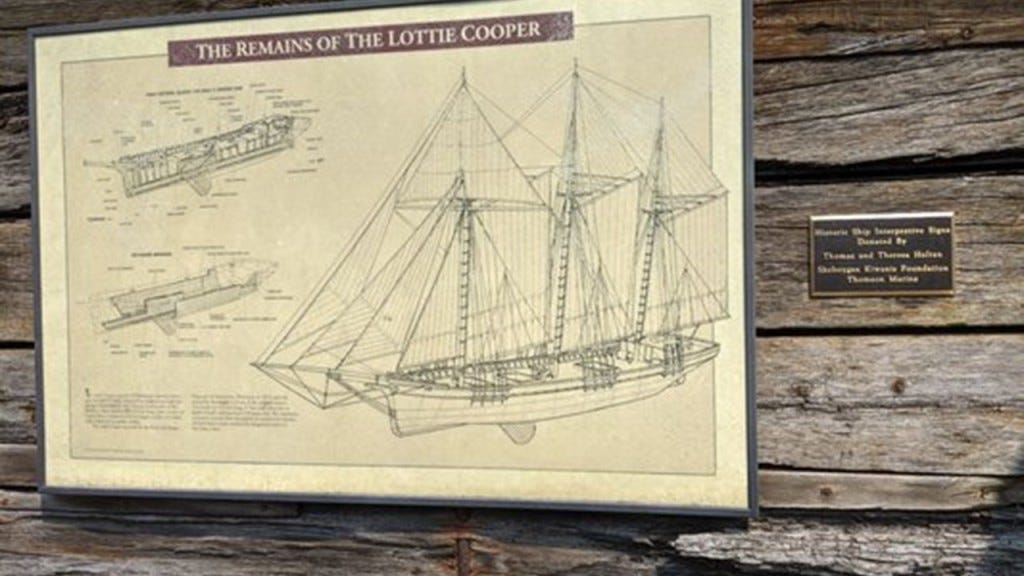

The Great Lakes Region is infamous for its shipwrecks, with an estimated somewhere between 6,000 to 10,000 ships and somewhere around 30,000 lives lost.

The reasons given for the high number of shipwrecks are severe weather, heavy cargo and navigational challenges.

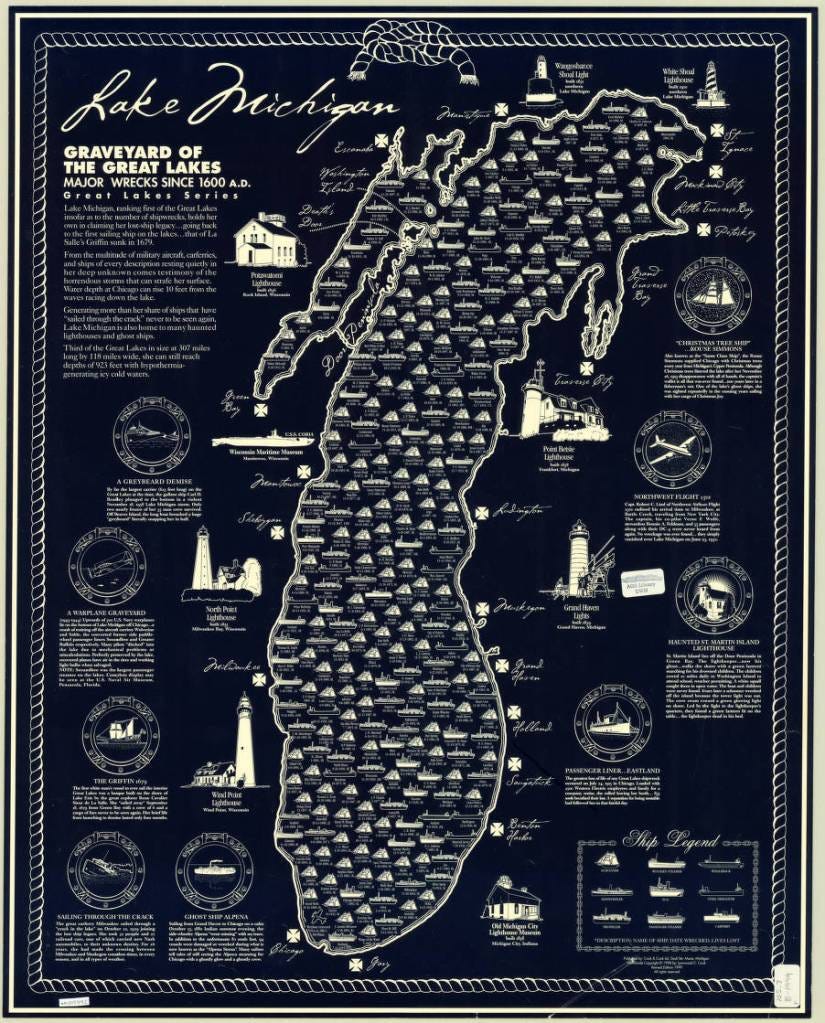

It is estimated that there are around 780 shipwrecks in Lake Michigan, with about 250 identified, and it has been nicknamed “Graveyard of the Great Lakes.”

It is estimated that there are between 350 and 550 shipwrecks in Lake Superior, many of which are still undiscovered.

I find it noteworthy that the Great Lakes region is very similar to other places that I have looked into that are known for the same kind of severe weather, shipwrecks, and have the same kind bathymetry that I shared previously ranging unevenly in-depth from shallow to quite deep.

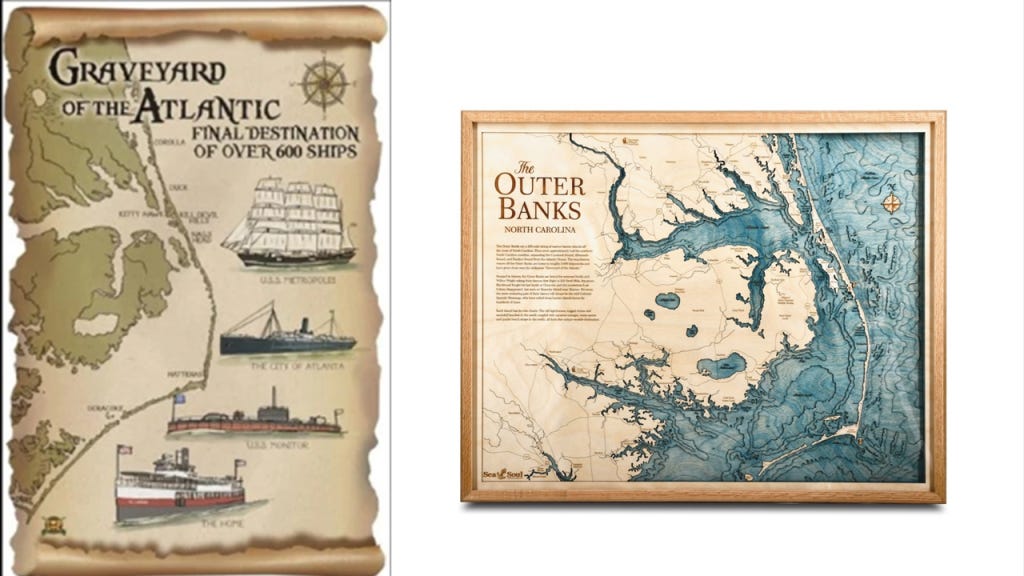

Places like Cape Cod in Massachusetts, which is known as a “Graveyard of the Atlantic” due to the large number of shipwrecks that have occurred here because of its dangerous shallows.

Here is the map showing fourteen lighthouses on Cape Cod alone, as well as other lighthouses of this part of New England, on the left, as well as the historic Old Colony Railroad that traversed the length of the narrow Cape Cod.

Like Cape Cod in Massachusetts, the treacherous waters of the Outer Banks have also given it the nickname of “Graveyard of the Atlantic” because of the numerous shipwrecks that have occurred here because of its treacherous waters consisting of things like shallows, shifting sands, and strong currents.

The reason we are given for the extreme weather in our official narrative is climate change, which is linked to the United Nations 2016 Paris Climate Agreement, and to all of the goals of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

But I have come to believe the explanation for the extreme weather could very well be found in things like the presence of ruined and sunken land just underneath the surface of the water from the deliberate destruction of the energy grid, and possibly creating instability where weather is concerned, and/or perhaps generating their own weather systems in their respective regions.

Or perhaps the creation of extreme weather may have some external help.

Like the wreck of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald mentioned in the last post as the most famous shipwreck of Lake Superior, the sinking of the Lady Elgin was the most famous shipwreck on Lake Michigan.

The Lady Elgin, a side-wheel steamship, was said to have been built in Buffalo, New York, in 1851.

For almost a decade, the elegant steamship took passengers between Chicago and other cities on Lake Michigan and Lake Superior.

Apparently during the years she was in operation, the steamship was involved in a number of accidents, including, but not limited to, things like striking a rock in 1854 and being damaged by fire in 1857.

Then On September 6th of 1860, the Lady Elgin was rammed below the water-line by the wooden Schooner Augusta, and her sinking has been called the “one of the greatest marine horrors on record.”

The Lady Elgin was on its return trip to Milwaukee, sailing against gale force winds, when she was rammed by the Augusta.

The Lady Elgin’s captain ordered that cattle and cargo be thrown over-board to lighten the load in order to bring the hold above-water.

All of the efforts to try to keep the ship from sinking came to nothing, as within twenty-minutes, the ship broke apart and sank quickly.

The Lady Elgin passenger manifest was lost, so the exact number on-board was unknown.

Of those 300 people, most were from the Irish community of Milwaukee, including nearly all of Milwaukee’s Irish Union Guard.

The Irish Union Guard was an Irish militia based in Milwaukee’s Third Ward, and who were at odds with the Wisconsin governor’s position.

The members of the Irish Union Guard had chartered the Lady Elgin for a quick-trip to Chicago.

It was said that so many Irish-American political operatives died that day that it shifted the balance-of-political-power in Milwaukee from the Irish to the Germans.

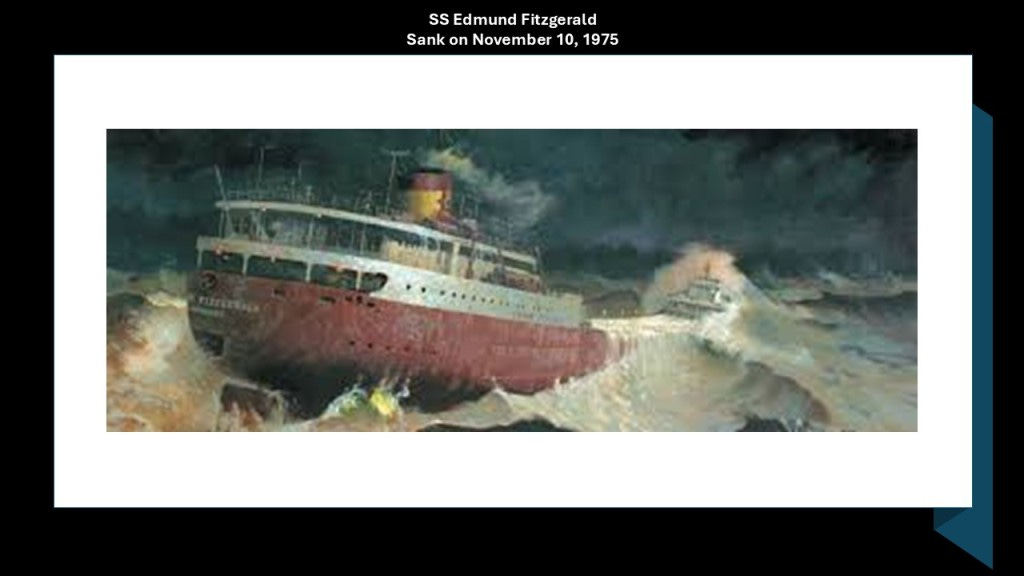

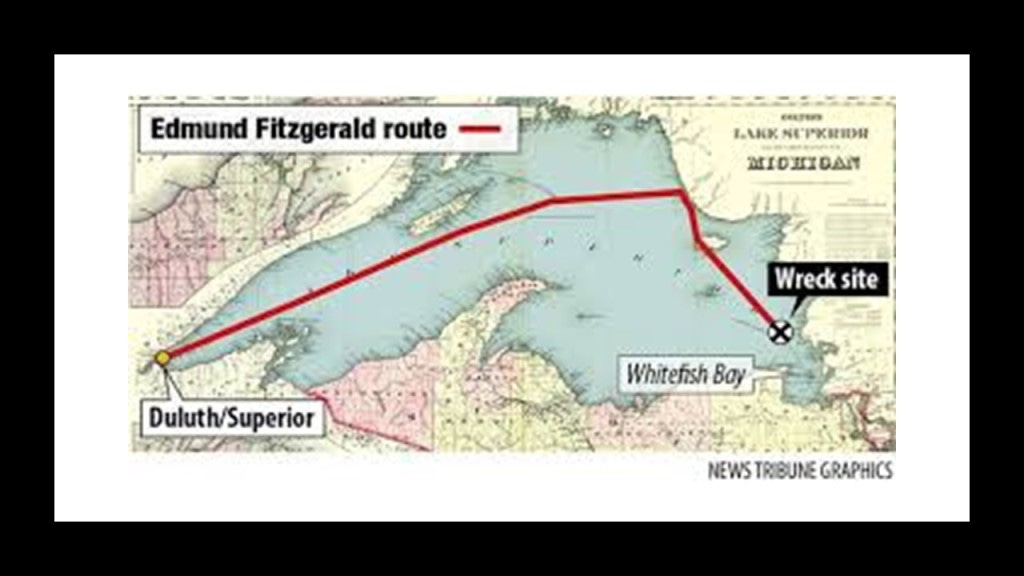

On the November day the SS Edmund Fitzgerald sank on Lake Superior in 1975, it and one other ship that didn’t sink, the SS Arthur M. Anderson, were heading to Detroit with a load of Taconite, a type iron ore, when they encountered a severe storm with hurricane-force winds and waves up to 35-feet, or 11-meters, high…

…when the SS Edmund Fitzgerald suddenly sank near Whitefish Bay in Lake Superior, and the entire ship’s crew perished.

Before I go into this journey looking at what’s found around Lake Michigan, I would like to mention an obscure historical figure named Lewis Cass, whom I learned about researching the State of Michigan in my series on who is represented in the National Statuary Hall at the U. S. Capitol in Washington, DC.

I learned a lot about obscured history and what the official historical narrative tells us about what has taken place here from the research I have done so far on who is represented there. After having gone through approximately half of the states, I have found that regardless of fame or obscurity, the National Statuary Hall functions more-or-less as a “Who’s Who” for the New World Order and its Agenda..

The State of Michigan is represented by Lewis Cass, as well as Gerald Ford.

Lewis Cass, an American military officer, politician and statesman, was a U. S. Senator for Michigan and served in the cabinets of two Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan.

Lewis Cass attended the Phillips-Exeter Academy, established in 1781 by Elizabeth and John Phillips, a wealthy merchant and banker of the time, and whose nephew, Samuel Phillips Jr, had established the Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts in 1778, making it the oldest incorporated school in the United States.

These two schools have educated several generations of the Establishment and prominent American politicians.

The Cass family moved to Marietta, Ohio, in 1800.

Marietta was the first permanent U. S. settlement in the newly established Northwest Territory, which was created in 1787, and the nation’s first post-colonial organized incorporated territory.

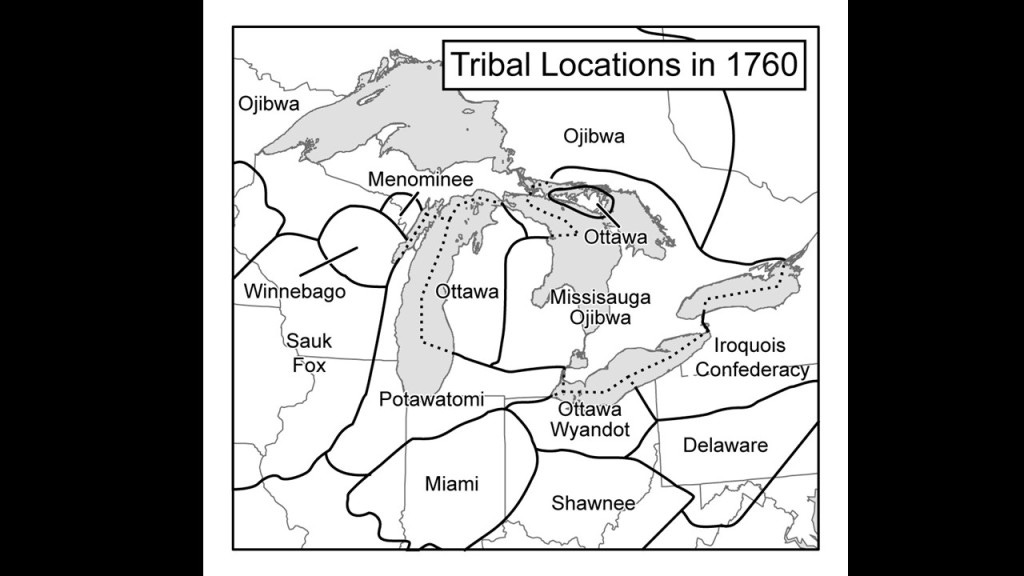

We are told the Northwest Indian War took place in this region between 1786 and 1795 between the United States and the Northwestern Confederacy, consisting of the indigenous people of the Great Lakes area.

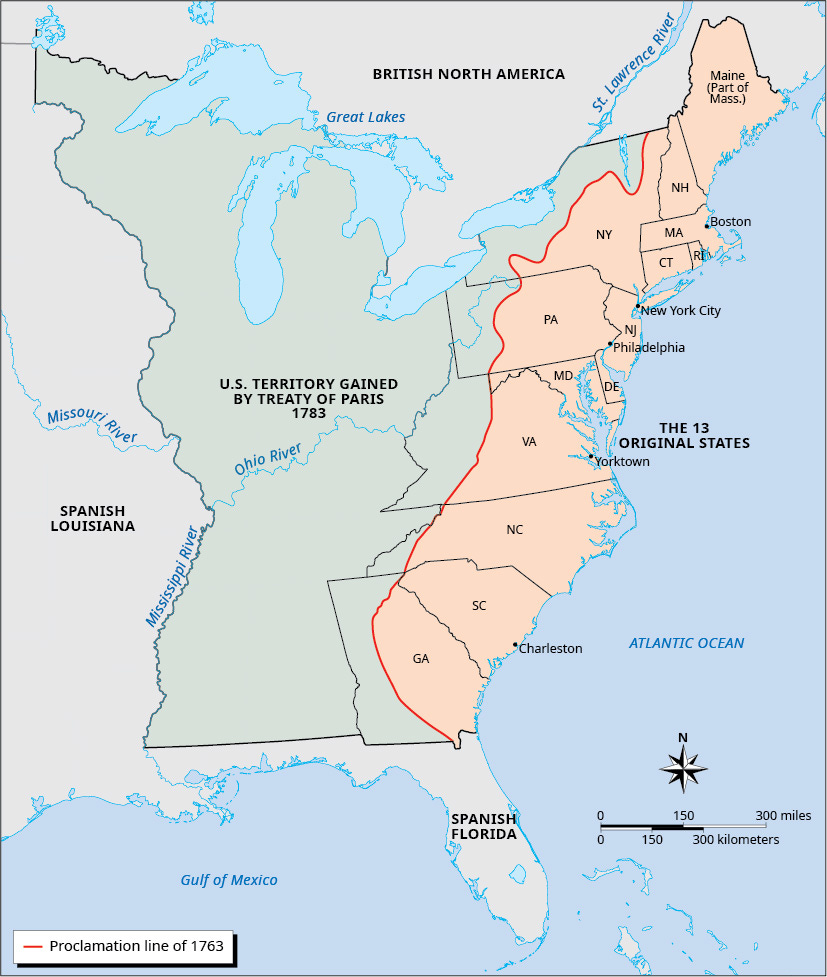

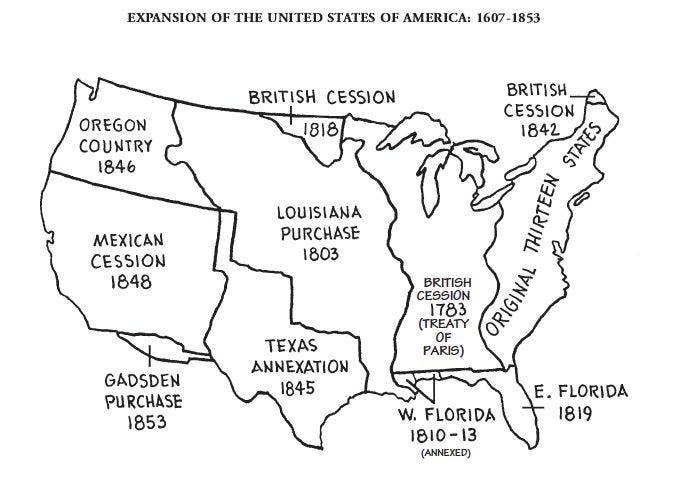

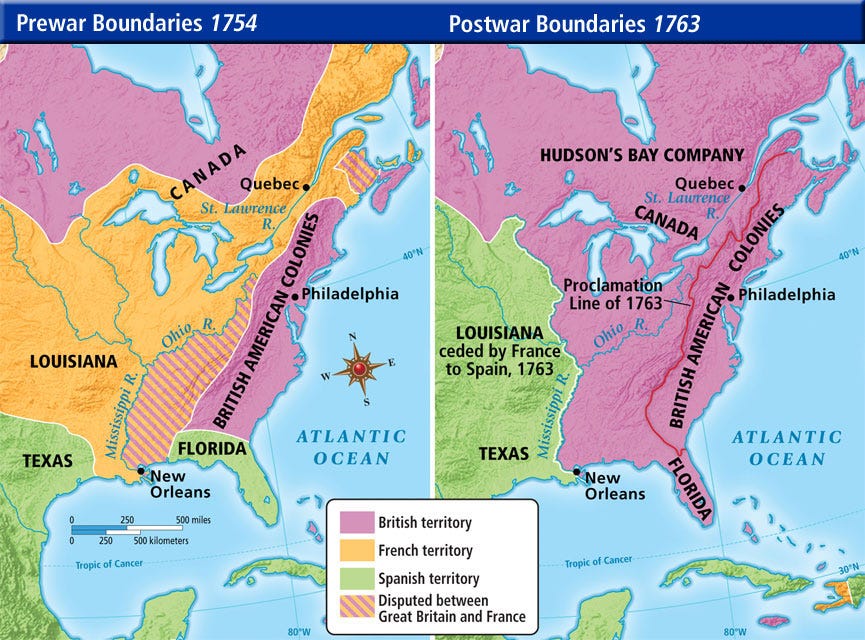

The Territory had been granted to the United States by Great Britain as part of the Treaty of Paris at the end of the Revolutionary War.

The area had previously been prohibited to new settlements, and was inhabited by numerous indigenous peoples, even though the British maintained a military presence in the region.

While the Northwestern Confederacy had some early victories, they were ultimately defeated, with the final battle being the “Battle of Fallen Timbers” in August of 1794 in Maumee, Ohio, which took place after General Anthony Wayne’s Army had destroyed every indigenous community on its way to the battle.

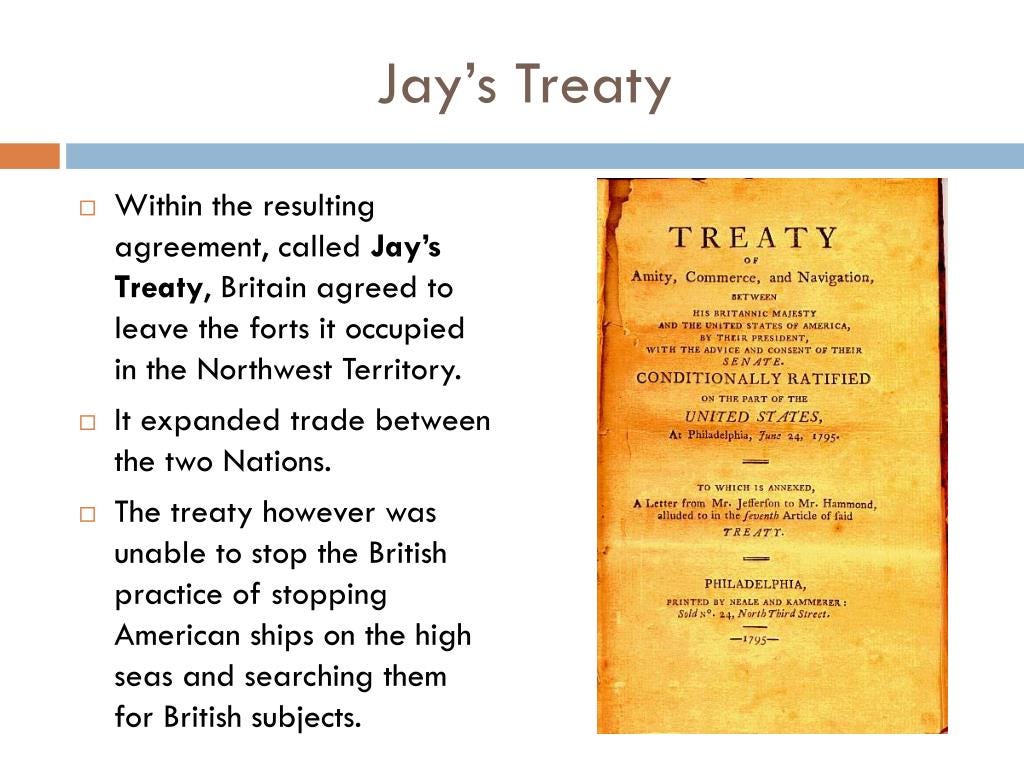

Outcomes were the 1794 Jay Treaty, named for Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay, the main negotiator with Great Britain.

As a result, the British withdrew from the Northwest Territory, but it laid the groundwork for later conflicts, not only with Great Britain, but also angering France and bitterly dividing Americans into pro-Treaty Federalists and anti-Treaty Jeffersonian Republicans.

The 1795 Greenville Treaty that followed forced the displacement of the indigenous people from most of Ohio, in return for cash and promises of fair treatment, and the land was opened for white American settlement.

Lewis Cass was elected to the Ohio House of Representatives in 1806, and the following year, President Thomas Jefferson appointed him as the U. S. Marshal for Ohio, the oldest U. S. Federal Law Enforcement Agency having been established by the Judiciary Act of 1789 during President George Washington’s administration to assist federal courts in their law enforcement functions.

Cass joined the Freemasons as an Entered Apprentice, the first degree of Freemasonry, at a lodge in Marietta in 1803 , and by May of 1804, he achieved the Master Mason degree, the third-degree of Freemasonry.

Lewis Cass was a charter member of the Lodge of Amity No. 5 in Zanesville, admitted in June of 1805, and was one of the founders of the Grand Lodge of Ohio in January of 1808, serving as its Grand Master multiple years.

We are told that during the War of 1812, Lewis Cass rose through the officer ranks to become a Brigadier General in the U. S. Army in March of 1813.

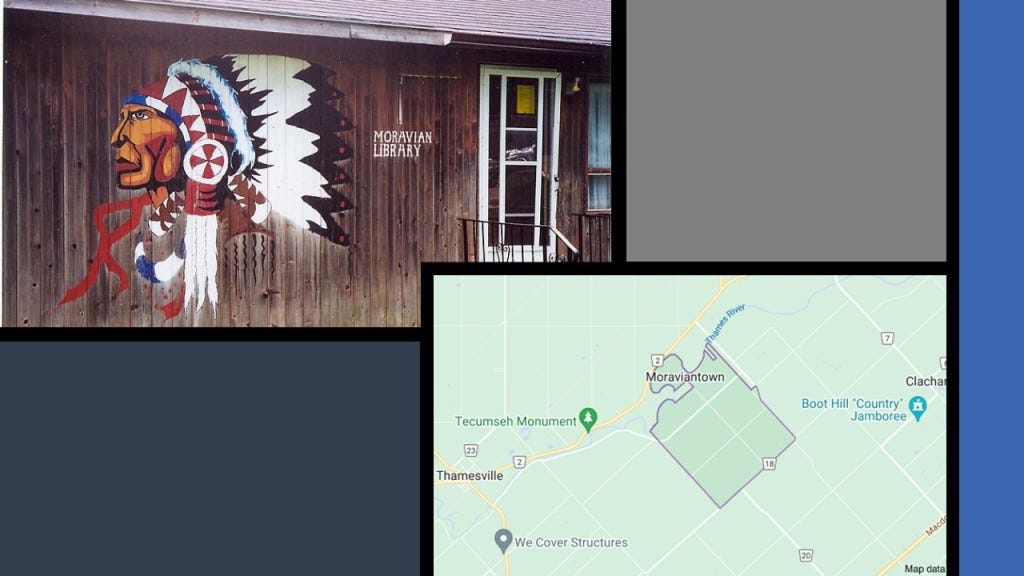

He took part in the Battle of the Thames, also known as the Battle of Moraviantown near Chatham, Ontario, and today’s Moravian on the Thames First Nation reserve, a branch of the Lenape who were converted to Christianity by Moravian missionaries from Pennsylvania, one of the oldest Protestant denominations.

At the time of the battle, the community of this First Nation, known as the Christian Munsee, was burned to the ground and rebuilt at its current location.

The Battle of the Thames in Ontario was an American victory in the War of 1812 against Tecumseh’s Confederacy, a confederation of Native people’s from the Great Lakes region, and their British allies.

As a result of the battle, Tecumseh was killed, his confederacy fell apart, and the British lost control of southwestern Ontario.

Cass was appointed as the Governor of the Michigan Territory by President James Madison in October of 1813, a position in which he served until 1831.

During this time, he travelled frequently to negotiate treaties with the indigenous peoples in Michigan, in which they ceded substantial amounts of land.

Cass was one of two commissioners who negotiated the Treaty of Fort Meigs, also called the Treaty of the Maumee Rapids, resulting the ceding of nearly all the remaining lands in northwestern Ohio, and parts of Indiana and Michigan, of the Wyandot, Seneca, Delaware, Shawnee, Potawatomi, Ottawa, and Chippewa, helping to open up Michigan to settlement by white Americans.

In return, land was allocated for reservations and financial compensation via annuities of various amounts for different lengths of time.

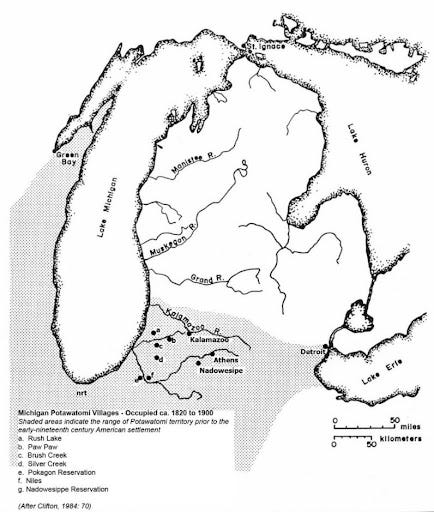

Other examples of the involvement of Lewis Cass with these land-acquiring treaties included, the 1819 Treaty of Saginaw with the chiefs and members of the Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi Tribes, in which they ceded 6-million acres of land, for which they were promised up to $1,000/year forever, and hunting and fishing rights on the land.

Cass was also involved with the 1821 Treaty of Chicago, in which he travelled to Chicago to try and get more land from tribal nations in Michigan.

As a result of this treaty, more Potawatomi, Chippewa and Ottawa tribes ceded land – this time nearly 5-million acres of the Lower Peninsula .

In return, they were promised about $10,000 in trade goods, $6,500 in coins, and a 20-year payment valued at about $150,000.

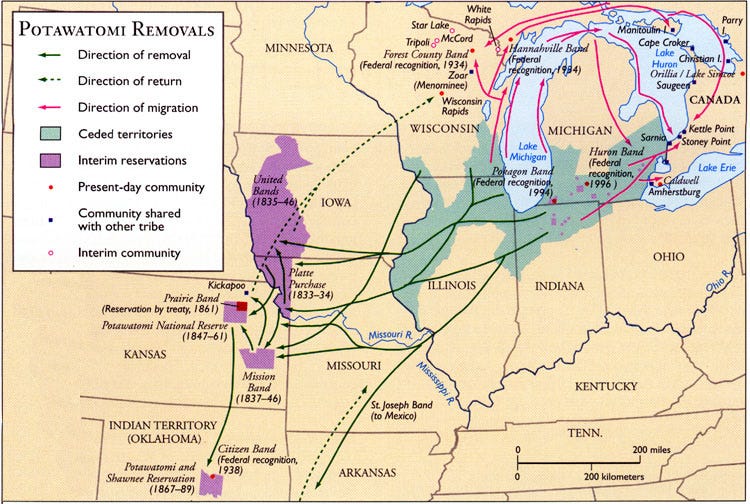

And where did all these treaties land them, like the Potawatomi?

A very long way from home!!!

Cass resigned as the Governor of Michigan in 1831 to become President Andrew Jackson’s Secretary of War, a position he would hold for the next 5-years.

As President Jackson’s Secretary of War, Cass was central in implementing the Indian Removal policy of the Jackson administration after Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830.

The Indian Removal Act was directed specifically at the Five Civilized Tribes of the Southeastern United States – the Cherokee, Creeks, Seminole, Chickasaw and Choctaw – though it also affected tribes in Ohio, Illinois and other areas east of the Mississippi River.

Most were forced to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska.

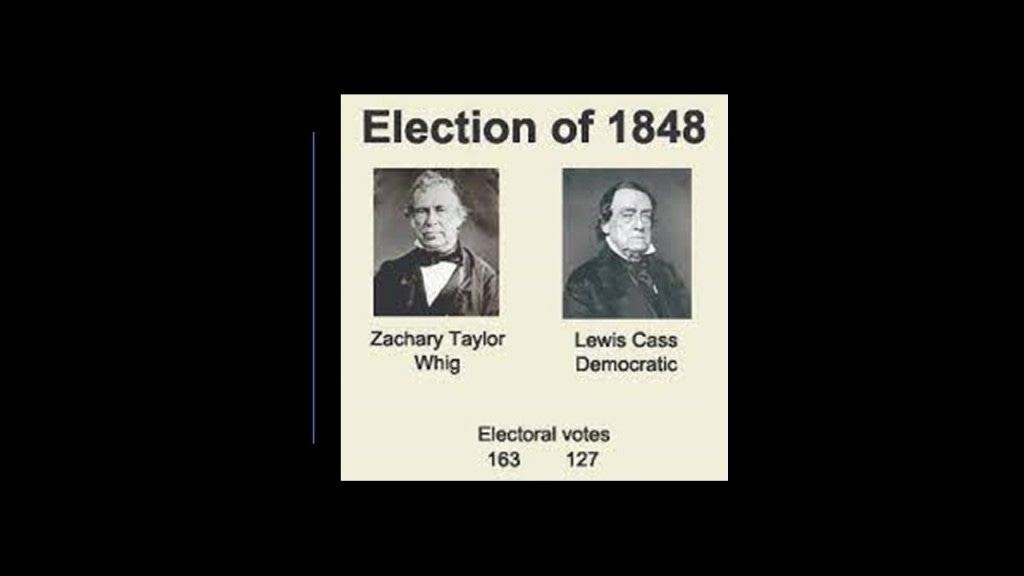

Cass was elected by the Michigan State Legislature in 1845 to serve as its United States Senator, a position he held until 1848 when he resigned in order to pursue an unsuccessful run for President that year.

After his loss to Zachary Taylor in the 1848 election, Cass was returned to the

U. S. Senate by the Michigan State Legislature, serving from 1849 to 1857.

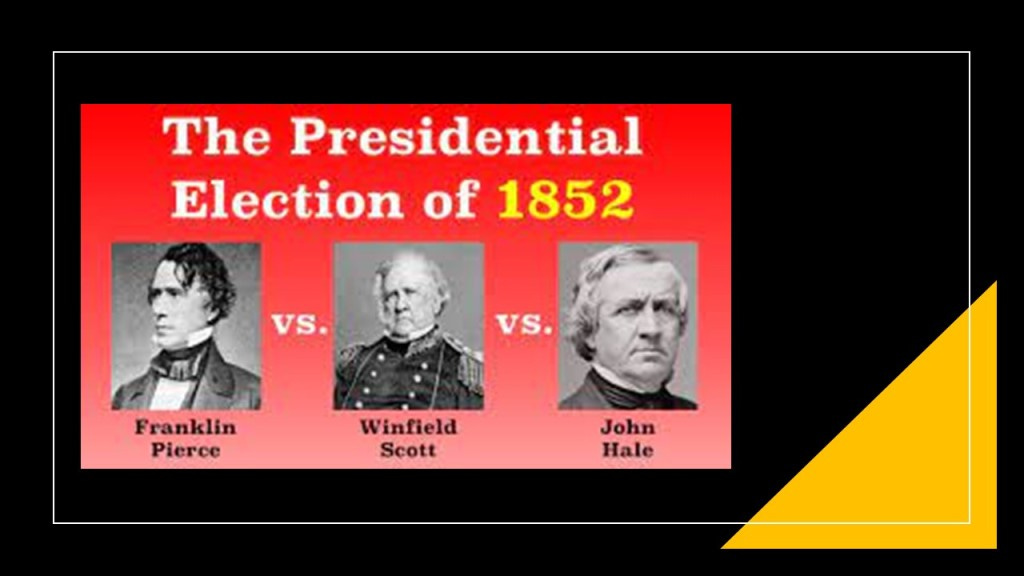

He ran and lost for President again in 1852, losing the Democratic nomination that year to Franklin Pierce, who became the 14th U. S. President.

A few years later, in March of 1857, President James Buchanan appointed an elderly Lewis Cass to serve as the Secretary of State in his administration around the same time he was retiring from the Senate.

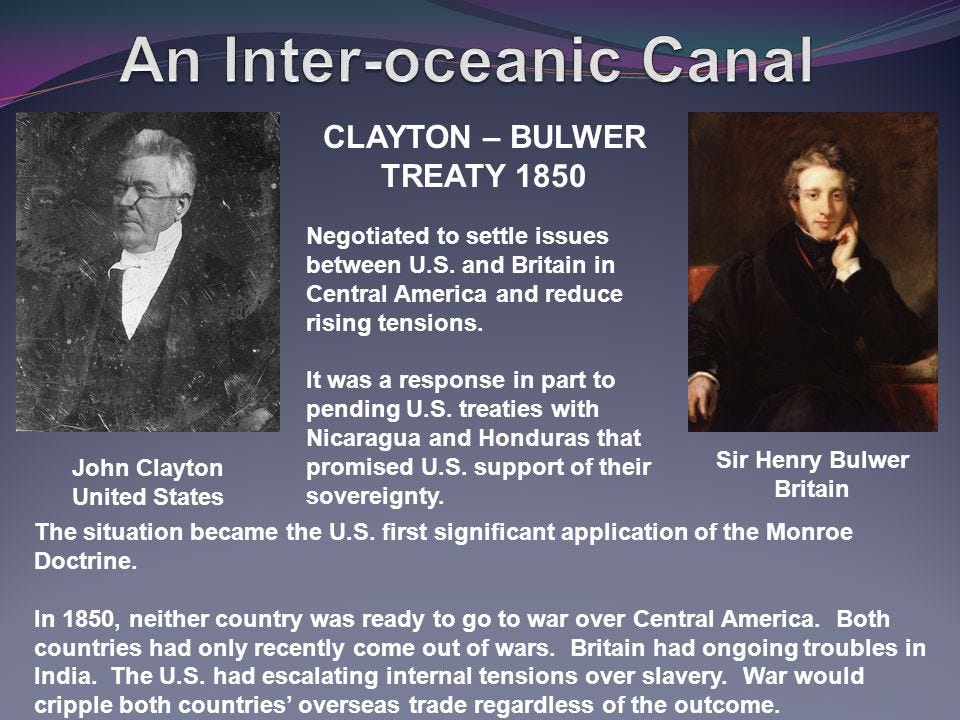

During his term of service as Secretary of State, Cass delegated most of his responsibilities either to an Assistant Secretary of State or to the President, though he was involved in negotiating a final settlement to the 1850 Clayton-Bulwer Treaty, which limited U. S. and British control of Latin American Countries.

Cass died in June of 1866 in Detroit, and was buried in the Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit, Michigan’s oldest continuously operating non-denominational cemetery, having been dedicated in October of 1846.

Descendents of Lewis Cass included great-grandson Augustus Cass Canfield, long-time President and Chairman of the Harper & Brothers Publishing Company (later known as Harper & Row)…

…and grandson Lewis Cass Ledyard, a New York City lawyer, personal counsel to financier J. P. Morgan, and a President of the New York Bar Association.

I am going to start this journey around Lake Michigan by looking at Mackinaw City and the area surrounding it at the top of what is called the “Lower Peninsula of Michigan,” also known as the “Mitten,” and I am going to end it at St. Ignace, across the Straits of Mackinac from Mackinaw City on the Upper Peninsula.

For the purposes of this post, I am only going to be looking at the Lake Michigan-side of the State of Michigan here.

Lake Michigan is hydrologically-connected to Lake Huron thorugh the Straits of Mackinac.

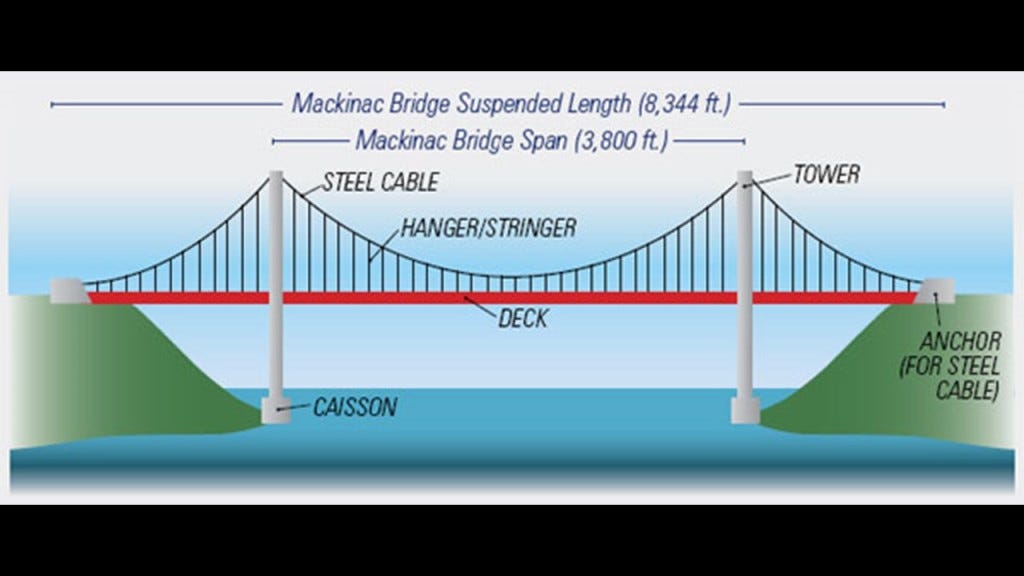

The Straits of Mackinac are the short waterways between the Upper and Lower Peninsulas of Michigan, and are crossed by the Mackinac Bridge, which was said to have first opened in 1957.

The Mackinac Bridge carries Interstate 75 across the longest suspension bridge between anchorages in the western hemisphere between Mackinaw City at its southern end, and St. Ignace at the northern end.

We are told the indigenous Ottawa people of this region, called the region around the straits “Michilimackinac.”

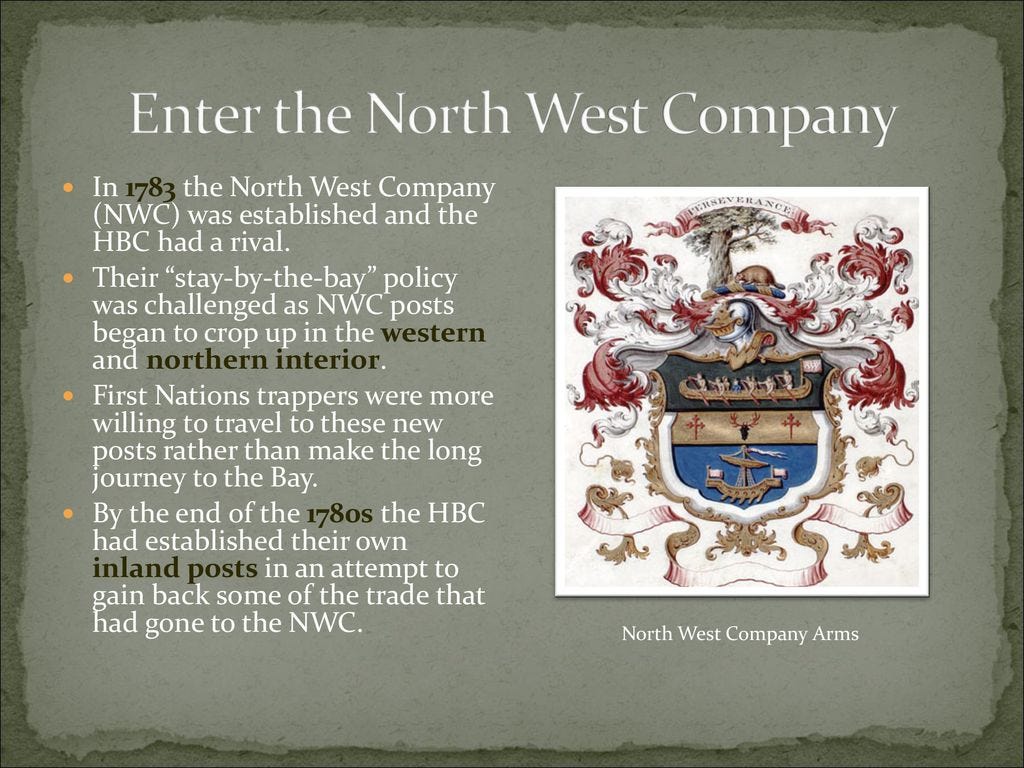

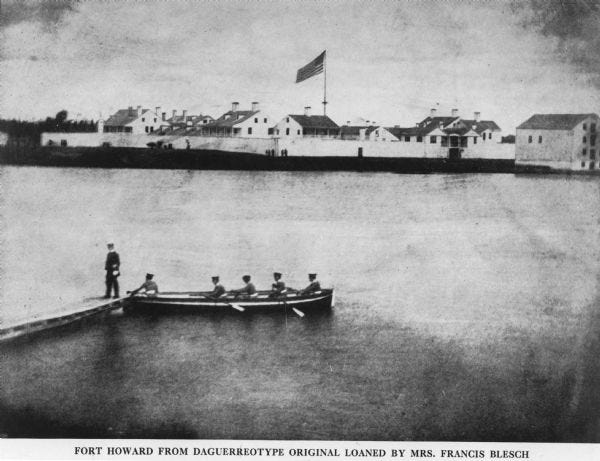

The Straits of Mackinac were an important fur-trading route and one of the four main fur-trading centers in the Great Lakes region established by the British North West Company, a fur-trading business based out of Montreal in Quebec from 1779 before it was forcibly merged with the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821, along with Grand Portage, Fort Niagara, and Fort Detroit.

This is what we are told in our official historical narrative, Fort Michilimackinac was built by the French as a trading post in 1715 in the location of today’s Mackinaw City.

Then in 1761, the French relinquished it along with their territory in Canada to the British following their defeat in the French and Indian War.

This “reconstruction” of it is found at Colonial Michilimackinac Historic State Park near the Mackinac Bridge.

The Old Mackinac Point Lighthouse is also in the Colonial Michilimackinac Historic State Park.

It was said to have been constructed in 1892 and deactivated in 1957, the same year the Mackinac Bridge was said to have first opened.

Here it is a photo on the right of this lighthouse with a Milky Way alignment, as was seen in part one of this series at five of the lighthouses on the Apostle Islands of Wisconsin on Lake Superior, as well as for comparison, two of the Lighthouses on the Great Ocean Road near the Twelve Apostles on the southeastern coast of Australia.

This lighthouse is a museum today.

The historic photo of this lighthouse on the top left reminds me of the creepy, staged-looking photos I have encountered in the seven-years I have been doing this research, all taken within 15-years of each other, like the photo on the top right, whichwas labelled as an 1895 photo of convicts working on the railroad in East Siberia near Khabarovsk; the 1870 photo on the bottom left taken in Trenton, New Jersey; and on the right, a photo taken in front of the Machinery Hall for the 1888 Centennial Exposition of the Ohio Valley and Central States in Cincinnati.

Some other lighthouses on this side of the Straits of Mackinac in the vicinity of the Old Mackinac Point Lighthouse that I would like to mention here are:

The McGulpin Point Lighthouse, which is 3-miles, or 4.8-kilometers, west of the Old Mackinac Point Lighthouse.

It was in operation as a lighthouse from 1869 to 1906.

Owned by Emmett County today, it was privately-owned and used as a residence at some point after it was deactivated in 1906, and then ownership passed to Emmett County in 2008.

The Waugoshance Lighhoust, said to have been built here in 1851, is described as a ruined lighthouse in a shoal area that is 15-miles, or 24-kilometers, due west of Mackinaw City.

We are told that due to erosion and deterioration, that lighthouse is critically-endangered, and likely to fall into the lake in the near future.

The Waugoshance Lighthouse is in the Wilderness State Park, called one of the most hazardous areas near the Straits of Mackinac.

The Wilderness State Park is described as a diverse forested, dune, and wetlands with swale complexes, with swale as a landform being defined as a sunken or marshy place.

The Wilderness State Park has also been designated as a “Dark Sky Preserve” since 2012, where light is restricted for astronomical observation and enjoyment, as seen here with a view of the Milky Way in the night sky.

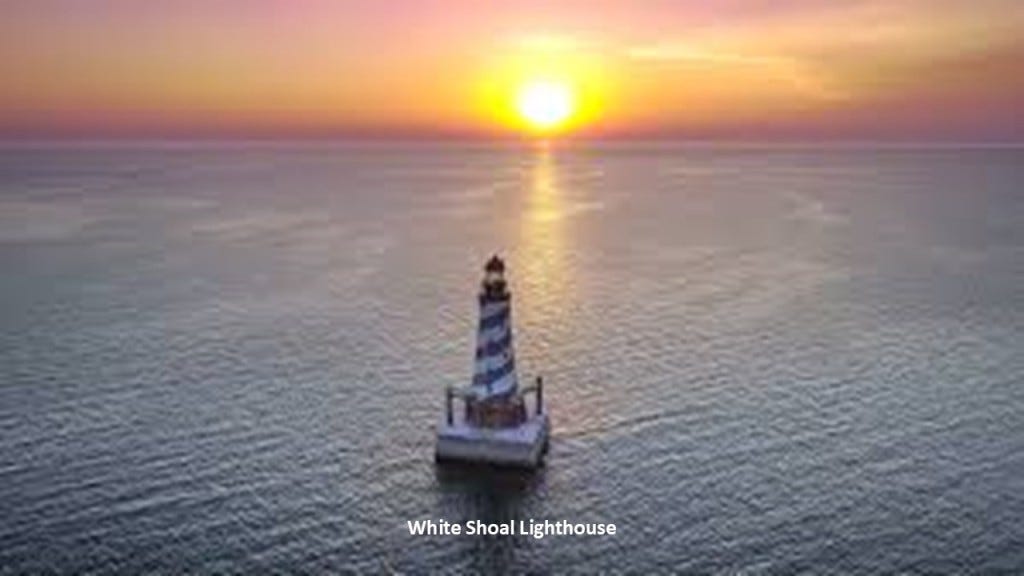

Besides the ruined Waugoshance lighthouse, there are three other lighthouses near the western end of the Wilderness State Park – the Grays Reef Light Station; the White Shoal Light; and the Aux Galets Lighthouse.

The White Shoal Lighthouse is located 20-miles, or 32-kilometers, west of the Mackinac Bridge.

It is still an active lighthouse, and the tallest lighthouse on Lake Michigan.

The construction of the current lighthouse here was said to have started in 1908, and first lit in 1910.

Here is the White Shoal Lighthouse in a solar alignment.

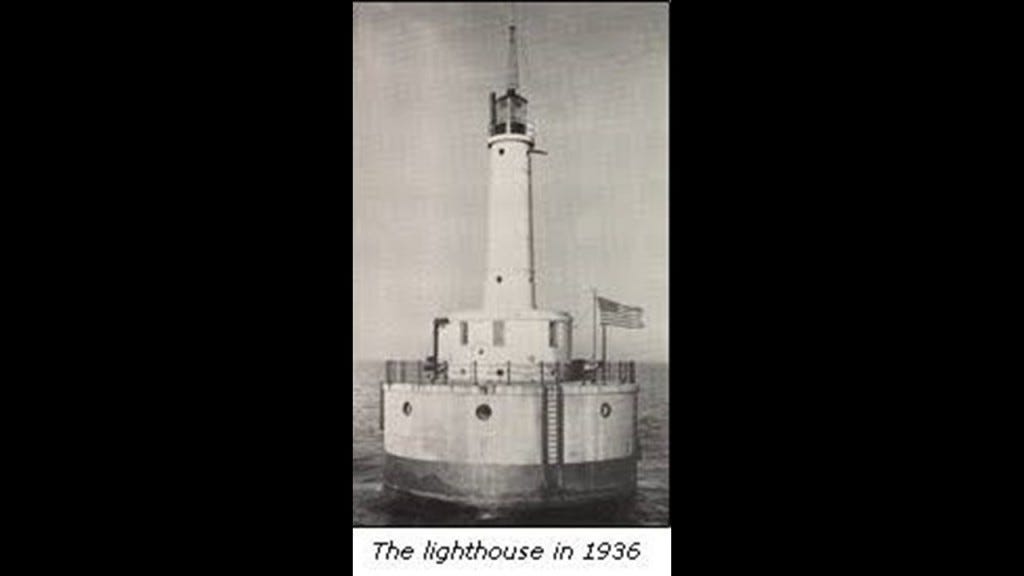

The Grays Reef Light Station is 3.8-miles, or 6.1-kilometers, west of the Waugoshance Lighthouse, said to have been built starting in 1934 on top of submerged stone and a concrete pier, and first lit in 1936, which all would have been during the Great Depression.

It is also an active lighthouse.

And the Aux Galets Lighthouse, also known as the Skillagee Island Lighthouse, is on a gravelly, low-lying island near the mainland and Sturgeon Bay.

The current lighthouse here was said to have been built in 1888 to warn shipping away from the reefs and shoals of Waugoshance Point, along with the other three lighthouses, which pose an imminent hazard to navigation.

As I said earlier in this post, I don’t believe at all that lighthouses were built to guide ships by whom they were said to have built them when they were said to have been built.

What I am seeing is that they ended up next to the edge of water when the land around them sank, and were repurposed into navigational aids in the New World to guide ships through the now broken landmasses in the surrounding waters.

I have come to believe “lighthouses” were literally “houses for light” for the purpose of precisely distributing light energy generated by this gigantic integrated system that existed all over the Earth that was in perfect alignment with everything on Earth and in heaven.

What I am seeing is that these were places that were in perfect resonance within a perfectly-resonant system, and that when the energy grid system was directly attacked, it caused the entire system around it to go haywire, and the surrounding land sank, or turned into like swamps, bogs, barrens, or deserts and dunes, as we are already seeing here at the Straits of Mackinac in Lake Michigan.

I am not drawing these conclusions from a few examples, but from many that I have found in years of doing research, including a lot of work tracking cities and places in alignment all over the Earth.

So now I’m going to back to Fort Michilimackinac for a moment in the location of the present-day Mackinaw City.

We are told the British continued to use Fort Michilimackinac built by the French as a major trading post until they decided the wooden fort was too vulnerable to attack from the indigenous people of the region in the 1760s, with Pontiac’s War going on, and so the British built a limestone fort on a high bluff on Mackinac Island in 1781.

I will look into this more in-depth when I look into Mackinac Island in the Lake Huron part of this series.

We are told in our historical narrative that Pontiac’s War was launched by the indigenous people in 1763 who were not happy with British rule in the Great Lakes Region, and lasted until 1766, and named after Pontiac, the Ottawa leader who was the most prominent of the many indigenous leaders in the conflict with the British.

I find it very interesting to note that there was a book by Francis Parkman published in 1851 titled “The Conspiracy of Pontiac.”

This book is still in-print today, and is considered the definitive account of the war.

Besides “The Conspiracy of Pontiac,” Francis Parkman was best-known for “The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky Mountain Life,” and “France and England in North America.”

He was born into a prominent Boston family, and as a child was said to be in poor health.

He entered Harvard at the age of 16, and graduated in 1844.

In 1843, when he was 20, he went on a Grand Tour in Europe, making his way through Italy.

I find this very interesting because this is not the first time I have found one man’s historical account that forms the basis for our history of events at a given time.

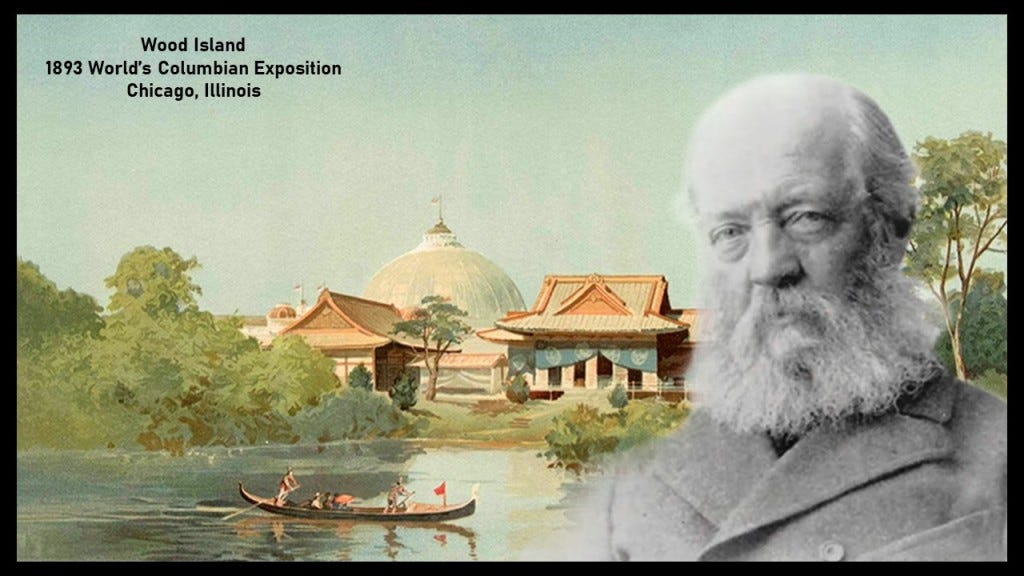

One of many examples of this is that Francis Parkman’s story and activities are very similar to those of Frederick Law Olmsted, who later in his life became the most celebrated landscape architect of the mid-to-late 19th- and early 20th-centuries, and called the “Father of Landscape Architecture.”

Olmsted’s biography says he created the profession of landscape architecture by working in a dry goods store; taking a year-long voyage in the China trade; and by studying surveying, engineering, chemistry, and scientific farming.

Though I found references saying he did attend Yale College, we are also told he was about to enter Yale College in 1837, but weakened eyes from sumac poisoning prevented him the usual course of study.

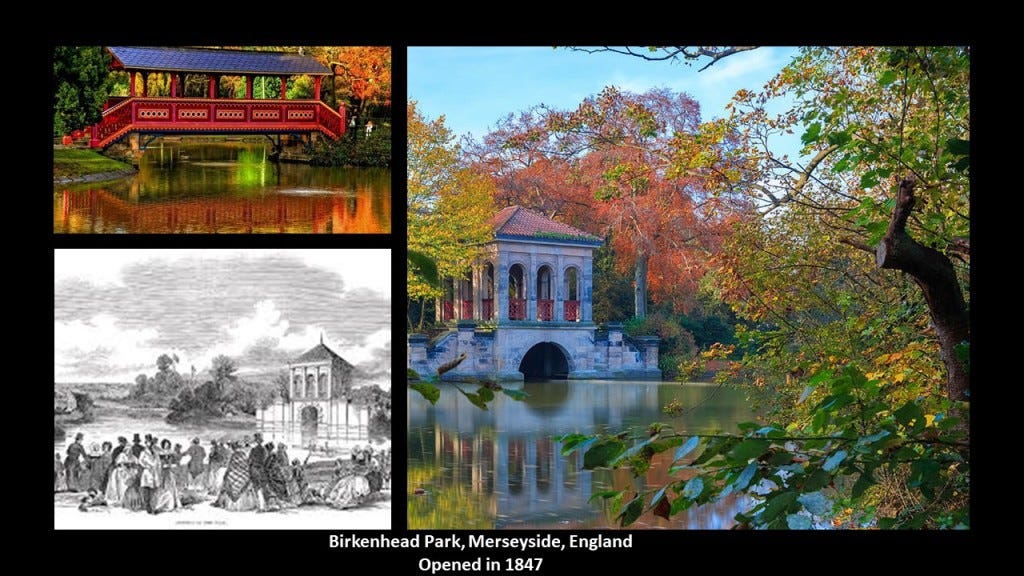

We are told he started out with a career in journalism, travelling to England in 1850 to visit public gardens there, including Birkenhead Park, a park said to have been designed by Joseph Paxton which opened in April of 1847 and said to be the first publicly funded civic park in the world.

Joseph Paxton, a greenhouse builder by training, was also given the historical credit for the designing of the Crystal Palace for the famous 1851 Exhibition in London, which was the same year Francis Parkman’s “The Conspiracy of Pontiac” was published as I just mentioned.

After his trip, Olmsted published “Walks and Talks of an American Farmer” in England in 1852, where he recorded the sights, sounds and mental impressions of rural England from his visit.

Frederick Law Olmsted apparently was also commissioned by the New York Daily Times to start on an extensive research journey in the American South and Texas between 1852 and 1857.

The dispatches he sent to the Times were collected into three books, and considered vivid, first-person accounts of the antebellum South: “A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States,” first published in 1856…

…”A Journey through Texas,” published in 1857…

…and “A Journey in the Back Country in the Winter of 1853 – 1854,” published in 1860.

All three of these books were published in one book, called “Journeys and Explorations in the Cotton Kingdom,” in 1861 during the first six months of the American Civil War at the suggestion of his English publisher.

One more thing is that he provided financial support for, and sometimes wrote for, “The Nation,” a progressive magazine that is the oldest continuously published weekly magazine in the United States, having been founded on July 6th of 1865, three-months after the end of the American Civil War.

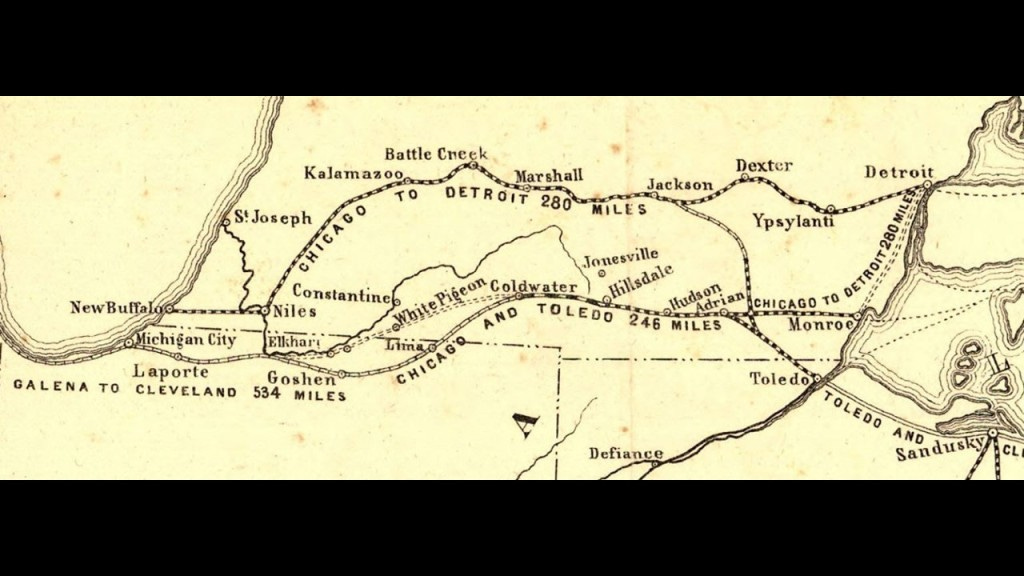

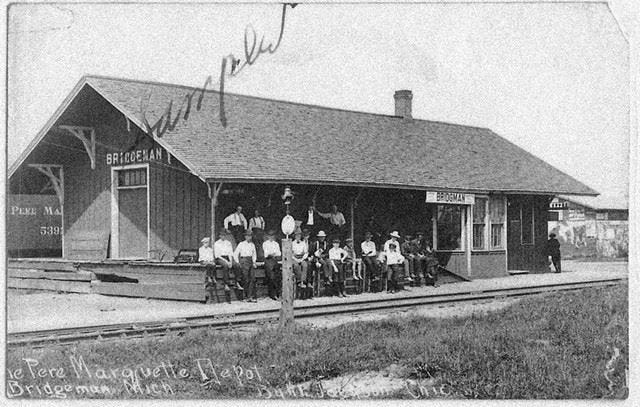

With regards to railroad lines to Mackinaw City, we are told that the Michigan Central Railroad came to Mackinaw City from Detroit in 1881, and the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad in 1882 connecting Mackinaw City to Traverse City; Grand Rapids; and Fort Wayne in Indiana.

These railroad lines facilitated passenger and freight transportation, which included railroad car ferries across the Straits of Mackinac.

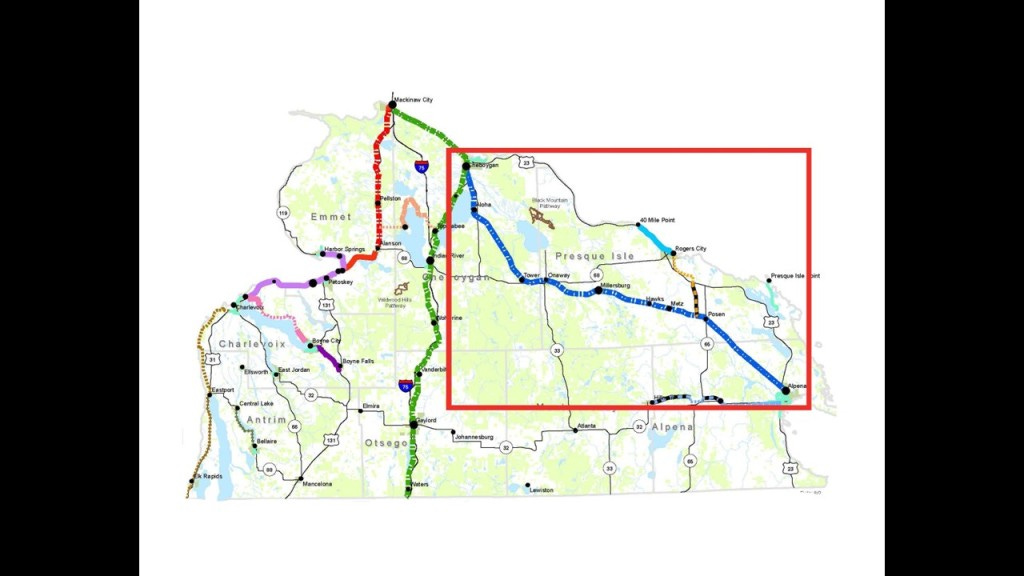

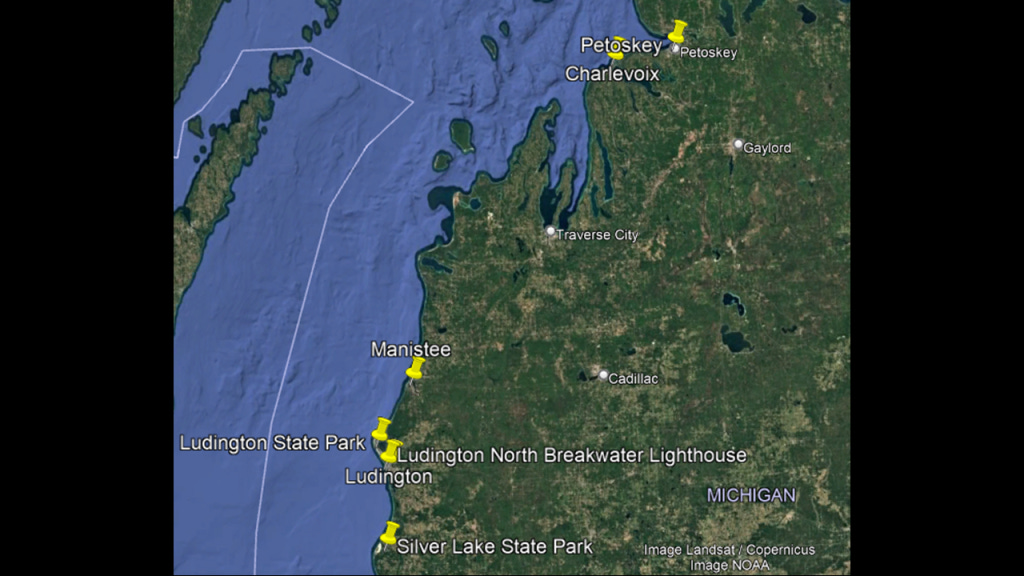

The former rail-lines have been repurposed into Rail-trails, like the North West State Trail from Petoskey…

…the North Central State Trail from Gaylord…

…and the North Eastern State Trail from Alpena.

There were two historic roundhouses in Mackinaw City, one for each of the railroads serving the area.

They were both demolished after the rail-lines leading to Mackinaw City were scrapped sometime in the 1980s.

The location of the former Michigan Central Roundhouse is now a Burger King, and the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad is a parking lot west of the Mackinac Bridge; and the former railyards a shopping mall.

Like the lighthouses, I believe that all the rail infrastructure was part of the original energy grid, and I believe the energy grid was deliberately destroyed, and that it’s destruction created everything we see in the world today that we are told is natural, including, but not limited to, the Great Lakes

I think the Controllers’ removed the rail-lines that were original part of the energy grid when they were no longer needed for mining and/or their agenda, and they only kept what was needed for freight, with keeping some for public transportation where it was critical infrastructure and scaled passenger service way-back from what it once was.

They were instead turned into interstates, highways, roadways, and recreational rail-trails. used for harvesting our energy for the benefit of a few from what was the original free-energy grid system for the benefit of all.

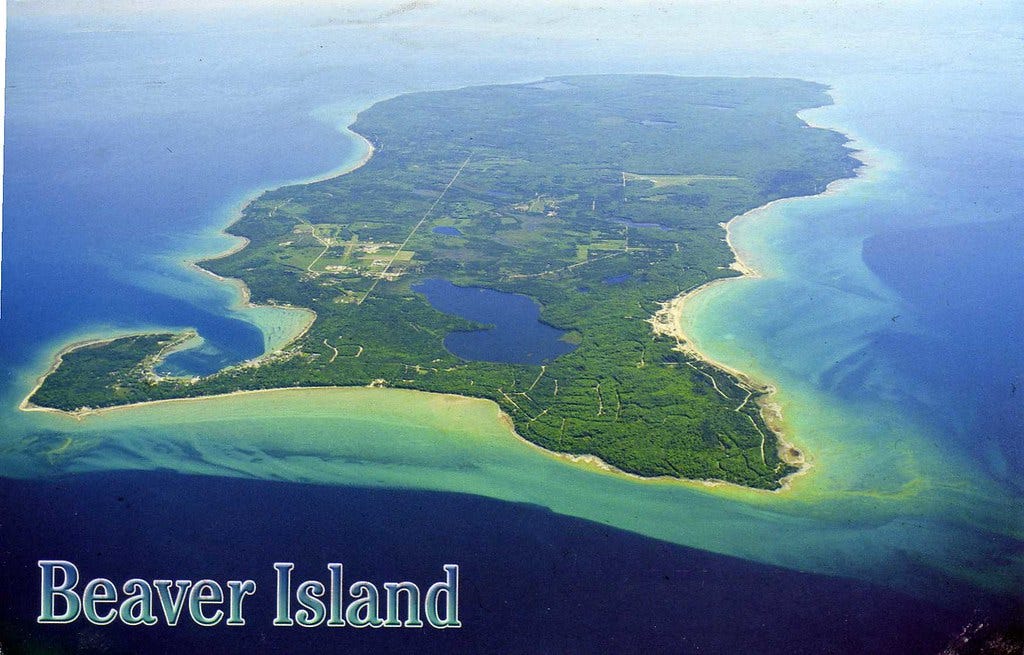

Before I move on down the western coast of Michigan on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan, I want to take a look at Beaver Island.

Beaver Island is the largest island in Lake Michigan.

The main access point for Beaver Island is Charlevois.

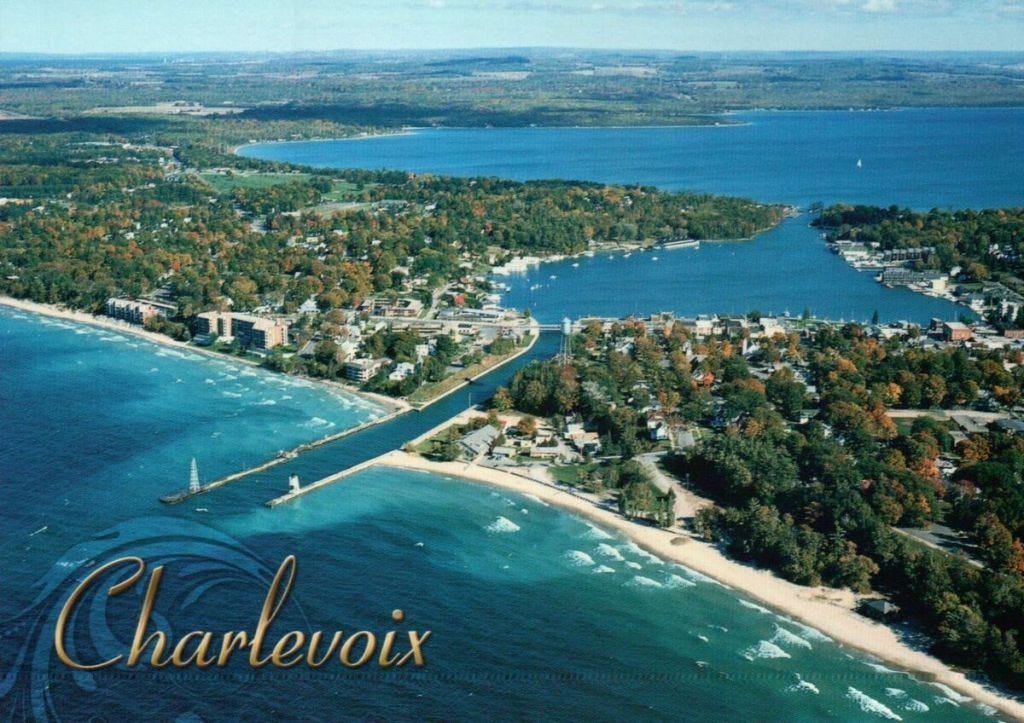

Charlevoix was named for the Jesuit explorer Pierre Francois Xavier de Charlevoix, who stayed the night on Fisherman’s Island during a harsh stomr sometime in the 1720s, which is located near his namesake city.

The Ottawa and Ojibwe peoples lived throughout northern Michigan prior to the arrival of the Jesuits and the European colonizers.

The Jesuit explorer Charlevois is known for the journal record he kept of his exploration of New France in present-day Canada and the United States first published in 1744 as the “History and General Description of New France.”

The city of Charlevois is located on isthmus, or narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across water.

This is not the only time we will see a city located on an isthmus in this post.

We are told that fishermen first settled what was known became known as Charlevoix around 1852.

We are told among other new arrivals as time went on, the Homestead Act of 1862 brought Civil War veterans and speculators up this way, with 160-acre tracts of land land selling for $1.25/acre.

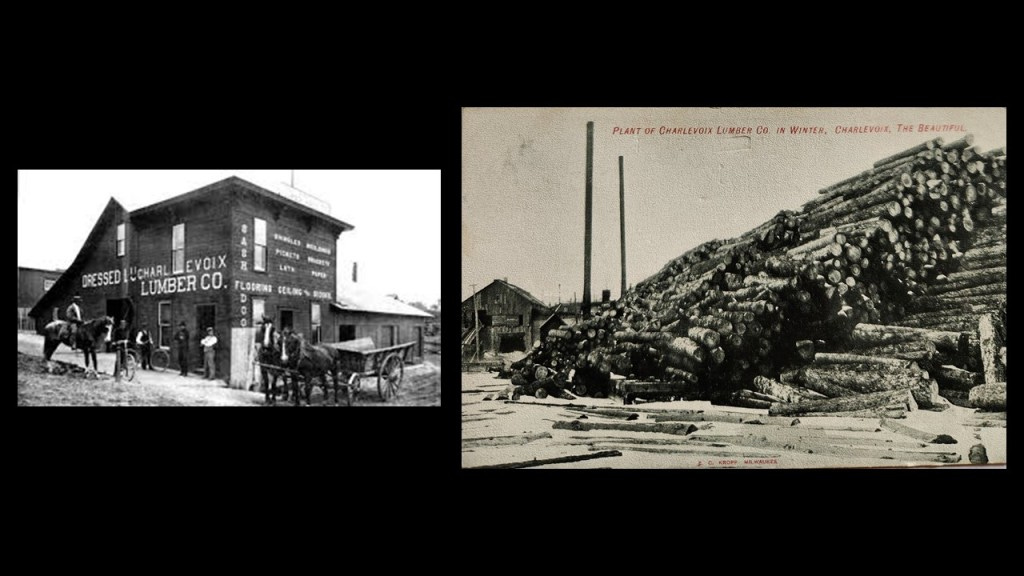

It is important to note that logging quickly became a thing, and lumber companies like the “Charlevoix Lumber Company” beginning in 1876, shipped out 40-million board feet of lumber before much of peninsula was stripped of its original forests.

There was actually a lot of activity of all kinds going on in and around Charlevois in its illustrious past, but today its population is less than 2,500 people as of the 2020 census.

Regular passenger train service to Charlevoix ended in September of 1962 when the Traverse City – Charlevois – Petoskey service was ended by the Chesapeake and Ohio (C & O) Railway.

Freight service ended between Charlevois and Williamsburg, Michigan, in 1982, when the C & O abandoned the track, and the tracks were removed in 1983.

The State of Michigan purchased the section of track between Charlevois and Petoskey, and it was run by the Michigan Northern Railway until a series of wash-outs in the 1990s, and this section of track was removed.

As we have already seen, sections of this rail-line serve as recreational rail-trails today and the old train depot is a museum of the Charlevois Historical Society.

Michigan Beach Park at Charlevoix is one of many beaches around this area, and is still very much a popular recreational spot in the present-day with its white sands and recreational facilities.

It is located right next to South Pierhead lighthouse at the end of what is called the “Pine River Channel.”

I have found things like piers and breakwaters, with lighthouses on the end, not only in the last part of this series on Lake Superior at Grand Marais in Minnesota…

…and Marquette in Michigan…

…but the same kind of configurations all over the world, like Dover in England in the English Channel…

…in Malta at the entrance to the Grand Harbor in the capital city of Valletta…

…and Sousse in northeastern Tunisia on the Gulf of Hammamet, to name a few of countless examples of harbor entrances with lighthouses.

We have always been told they were built as navigational aids for ships, but as I have already indicated, I think they were serving another purpose entirely in the energy grid system that we haven’t been told about.

Lake Michigan has many beaches, and is frequently referred to as the “Third Coast” of the U. S. after the Atlantic coast and the Pacific coast.

Called “singing sands,” the sand is often soft and white, or off-white, and squeaks when walked upon, believed to be caused by the high quartz content of the sand.

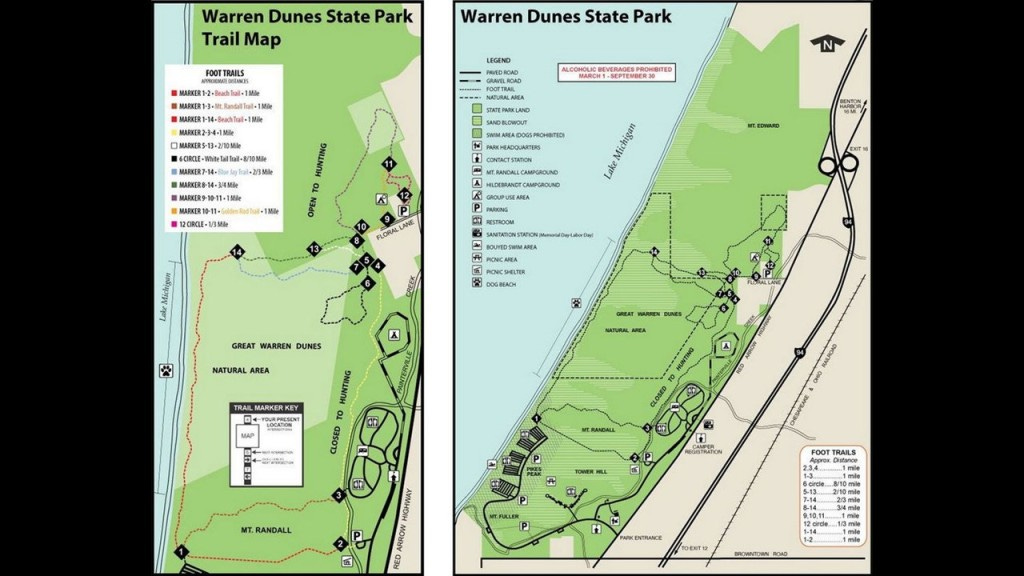

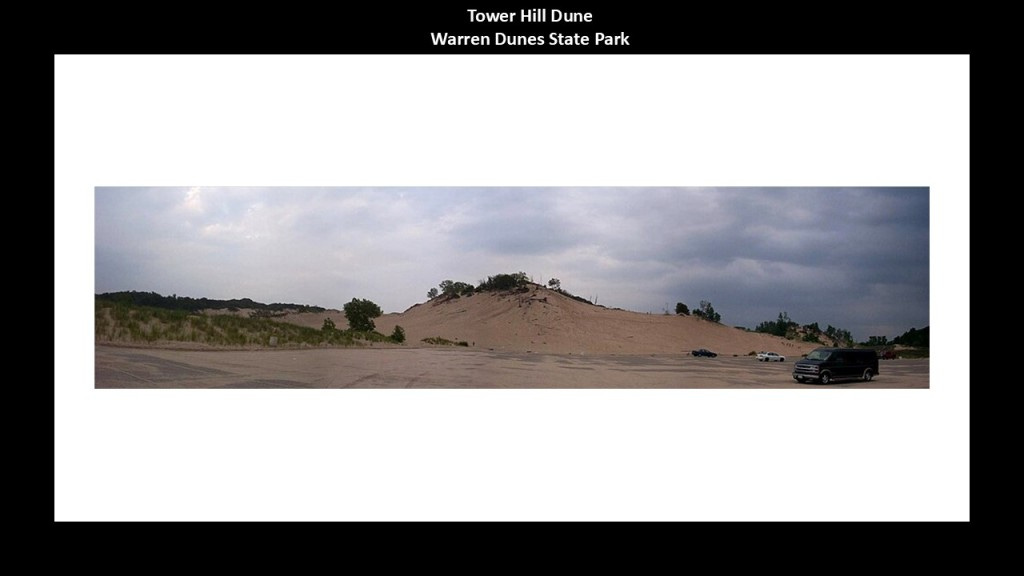

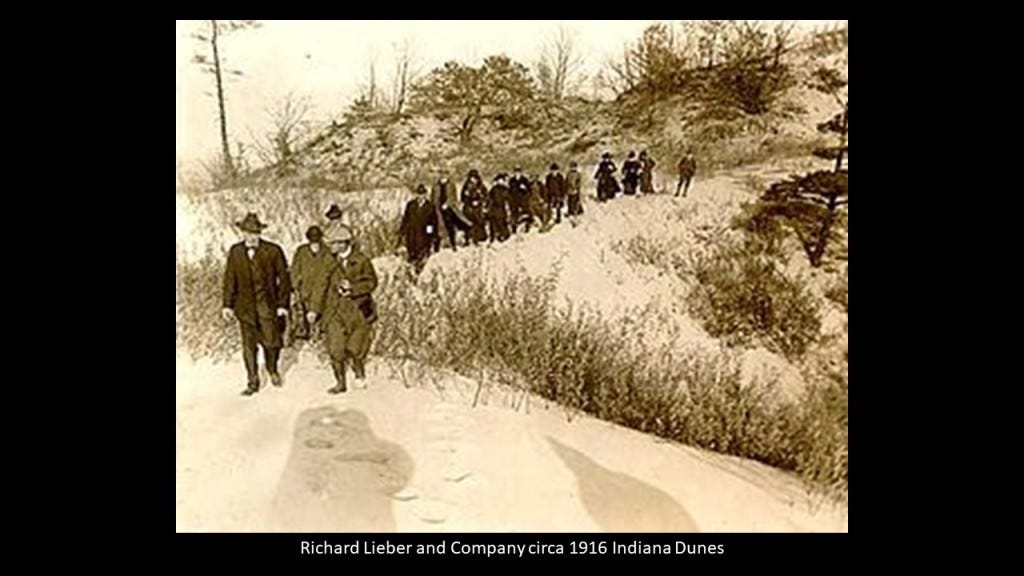

I am going to be looking at some of the sand dune systems as I go along the coast line of Lake Michigan in ths post.

The sand dunes located on the east shore of Lake Michigan are considered the largest freshwater dune system in the world.

Large dune formations can be seen in many state parks, national forests and national parks along the Michigan and Indiana shoreline.

Well, I thought I was out of Charlevoix, but something came up on my social media feed about castles in Michigan, and one of them was in Charlevoix, so I had to look into it.

What I found in Charlevoix was “Castle Farms.”

It was said to have been originally built in 1918 by the acting President of Sears, Roebuck, and Company, Chicago attorney Albert Loeb, as a dairy farm that was modelled after the stone barns and castles he had seen in Normandy, France.

At one time, it had 200-head of prize-winning Holstein-Friesien dairy cows and 13-pairs of Belgian draft horses.

Since then it has passed through different ownership but it has been serving as primarily as an event venue throughout the years.

So now back to Beaver Island.

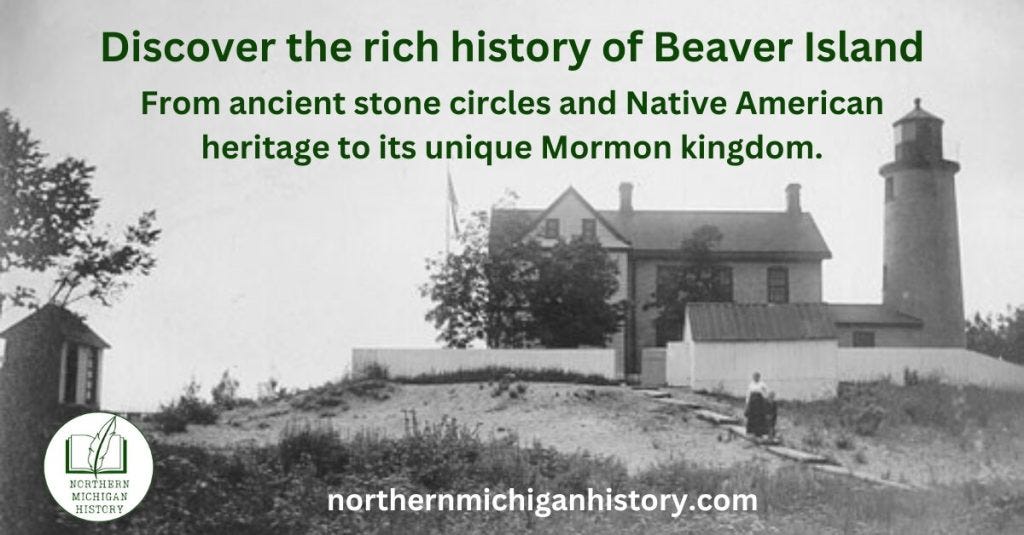

There are several thing that stand out about this location.

The first is that we are told there are at least one stone circle found here.

It is called the “Beaver Island Sun Circle,” also known as the Beaver Island Stonehenge, complete with astronomical alignments.

The next is that Beaver Island was the location of a relatively-short-lived Mormon theocratic kingdom from 1848 until his assassination in 1856, where the Mormon leader James Strang appointed himself king and took over the island there with his followers, who were known as Strangite Mormons.

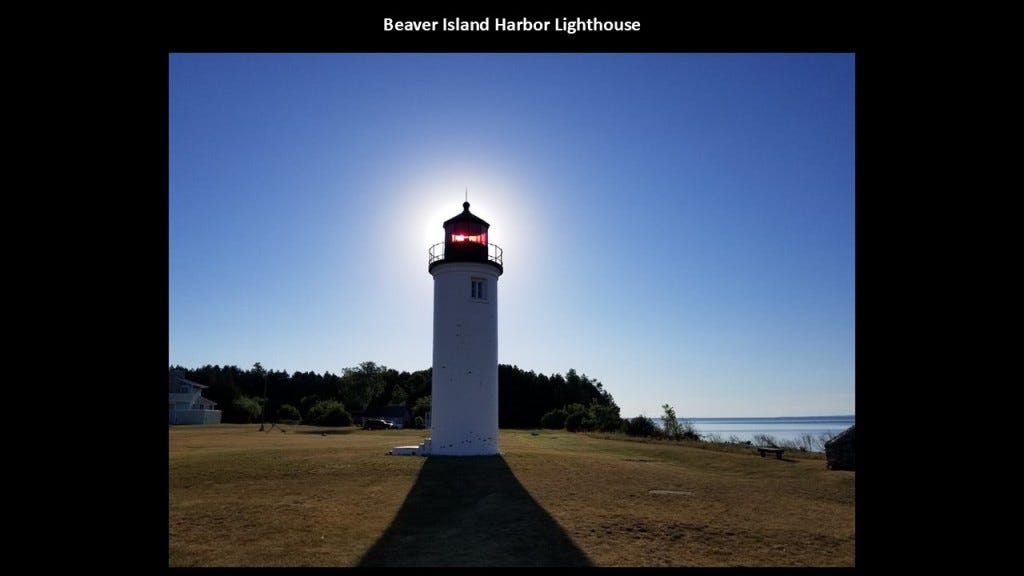

The last thing I want to mention is that Beaver Island has two lighthouses – the Beaver Island Harbor Lighthouse and the Beaver Head Lighthouse, along with several others on the western end of the Straits of Mackinac.

The Beaver Island Harbor Lighthouse is located in St. James, an unincorporated community apparently named for himself by the self-proclaimed King, James Strang.

We are told the original lighthouse here was constructed in 1856, and the one currently there in 1870, and is still an active lighthouse today.

Here it is seen with a solar alignment behind the top of the lighthouse.

The Beaver Head Lighthouse is located on a bluff on the southern end of Beaver Island.

We are told boats have to navigate very carefully between Gray’s Reef and Beaver Island.

We are told the Beaver Head lighthouse was operational between 1858 and 1962, and that in 1975, the Charlevoix Public Schools purchased the location for $1.

Since 1978, there has been an Environmental and Vocational Educational Center in the Keepers building and the lighthouse is open to the public in the summer months from 8 am to 9 pm.

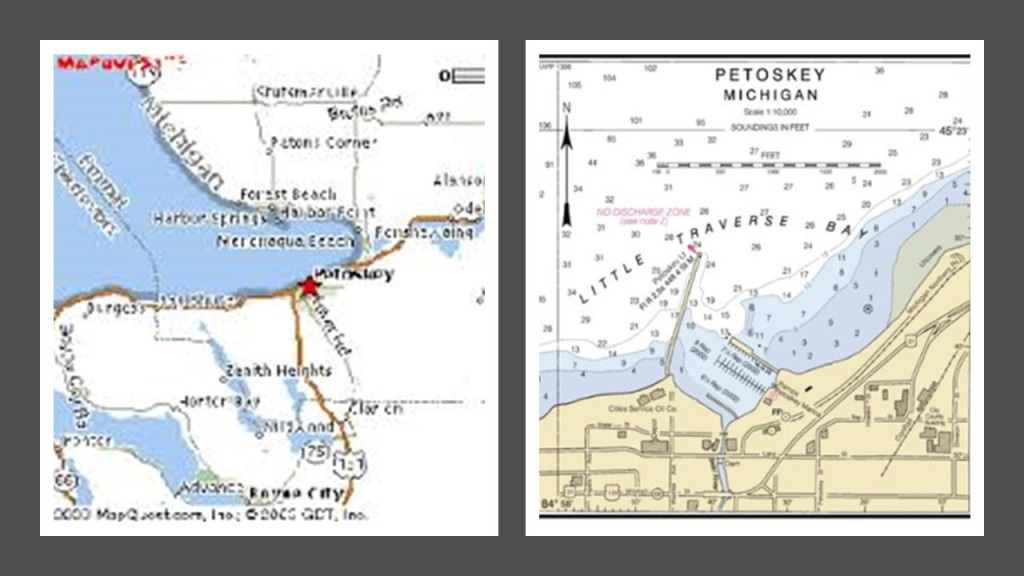

Now the next places I am going to take a look at on the eastern coast of Lake Michigan are the city of Petoskey and Grand Traverse Bay on either side of Charlevoix.

First, the city of Petoskey, which is located on Little Traverse Bay.

What we are told about Petoskey is this.

This area was long-inhabited by the Ottawa people.

Then, in the 1836 Treaty of Washington, we are told representatives of the Ottawa and Chippewa Nations ceded an area of approximately 13, 837,207-acres, or 55,997-kilometers-squared in Michigan in the northwest portion of the Lower Peninsula and the eastern portion of the Upper Peninsula, or approximately 37% of the current land area of the State of Michigan, and that this treaty was concluded on March 28th of 1836 by the Indian Commissioner of the United States, Henry Schoolcraft, and representatives of the Ottawa and Chippewa Nations.

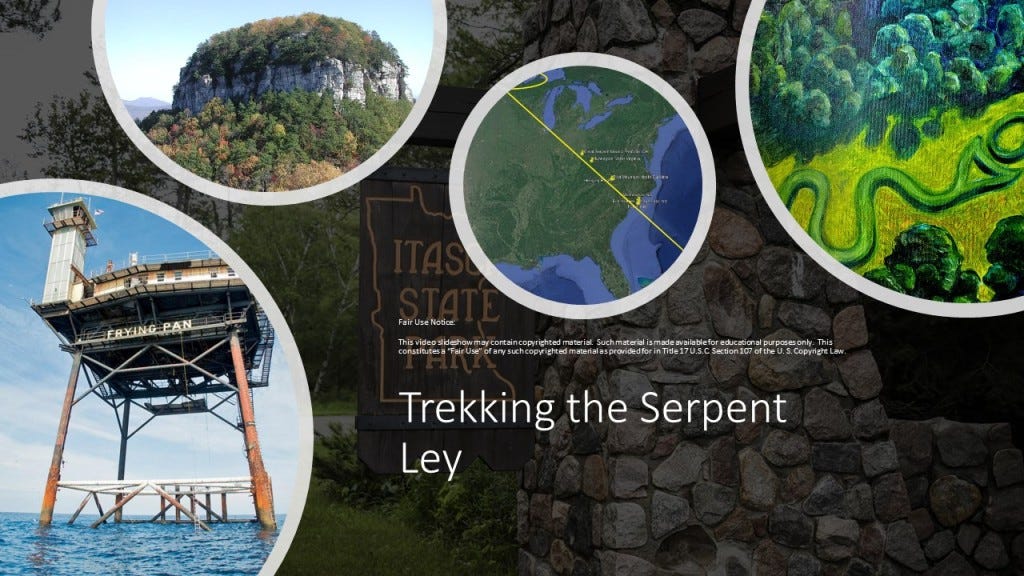

I first encountered the historical figure of Henry Schoolcraft when I was “Trekking the Serpent Ley” from the Bermuda Triangle to Lake Itasca in Minnesota back in August of 2023.

Lake Itasca is not far from Lake Superior and in the Great Lakes Region of North America.

The Itasca State Park was established in 1891, we are told, to preserve remnant stands of virgin pine and to protect the basin around the Mississippi’s source.

In 1832, Henry Schoolcraft, a geographer, geologist, and ethnologist, was part of an expedition that determined the source of the Mississippi River was Lake Itasca

He also appears to have been a Freemason as well.

Then in 1847, Congress commissioned Schoolcraft to do a comprehensive reference work on the history, culture, and social mores of Indian tribes throughout North America, and which was published in six-volumes between 1851 and 1857.

So not only did Henry Schoolcraft find the source of the Mississippi River in our historical narrative, he himself was likely one of the sources of the new narrative about the indigenous people as well.

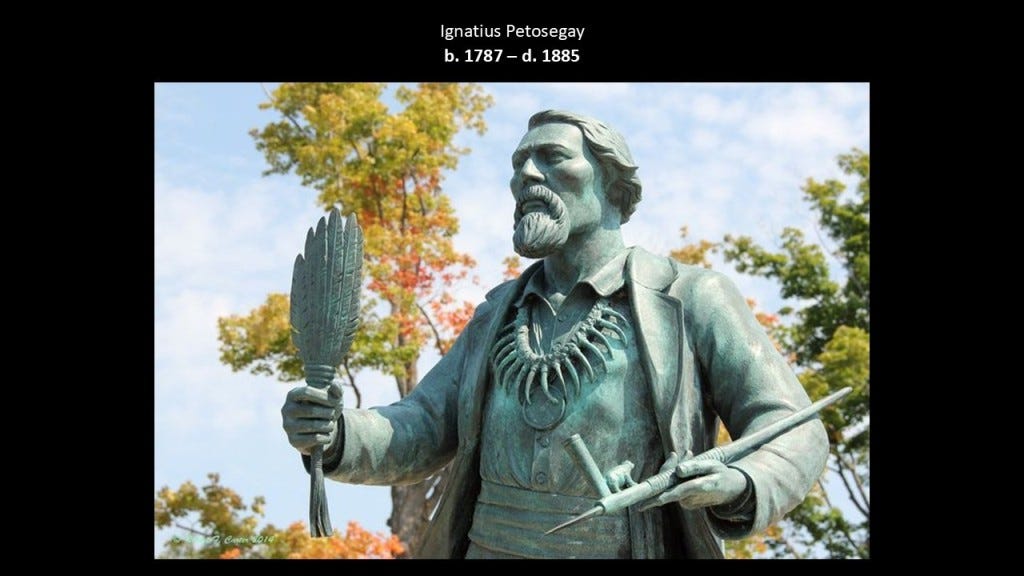

We are told Petoskey was named after the Ottawa chief Ignatius Petosegay, whose father was a French explorer and fur-trader, and whose mother was the daughter of an Ottawa chief, who purchased lands near the Bear River at some point after the Treaty of Washington was signed.

With the arrival of Jesuit missionaries to the area in the 19th-century, the man who became known as Ignatius Petosegay was befriended by the Jesuits, who renamed him after St. Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order.

The Bear River is described as a “small, clear tributary of the Little Traverse Bay.”

This photo of the right-angled waterfall and masonry banks of the Bear River going through the city of Petoskey…

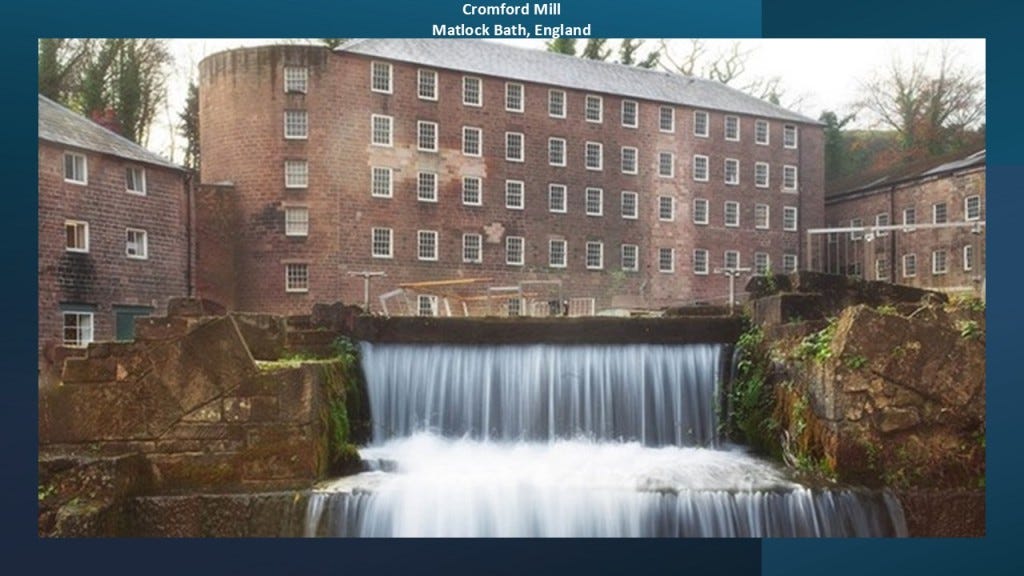

…is very reminiscent of examples I have seen on the River Derwent in Derbyshire, England, like at the Cromford Mill near Matlock Bath, the home of the world’s first water-powered cotton spinning mill…

…and the Vantaa River flowing through Helsinki in Finland also has such sights as right-angled waterfalls.

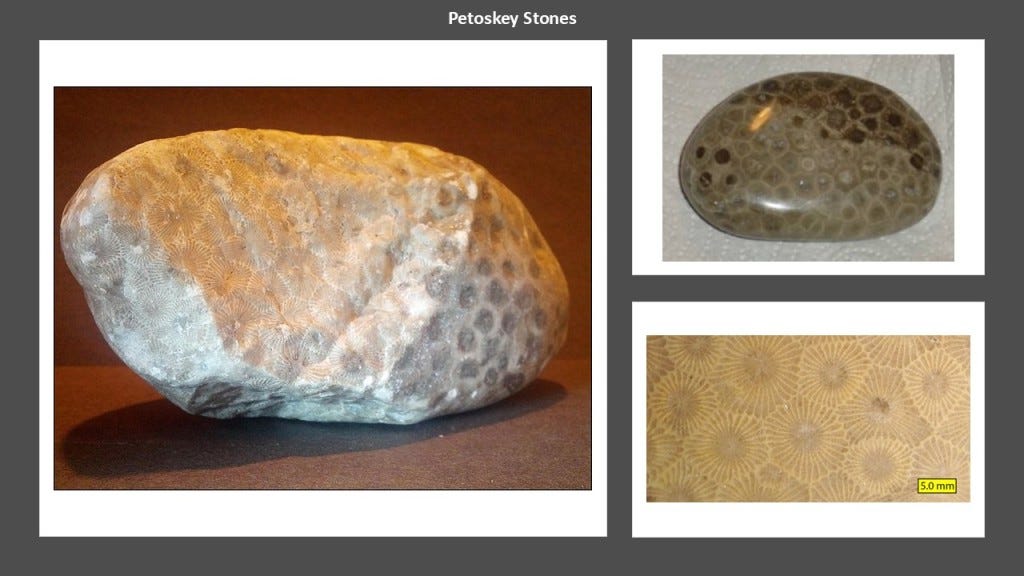

What are known as Petoskey stones, the official Michigan state stone, can only be found on northern Michigan beaches and inland lakes.

Today beachcombing for Petoskey stones with their honeycomb-like pattern is one of the favorite summer activities in Michigan.

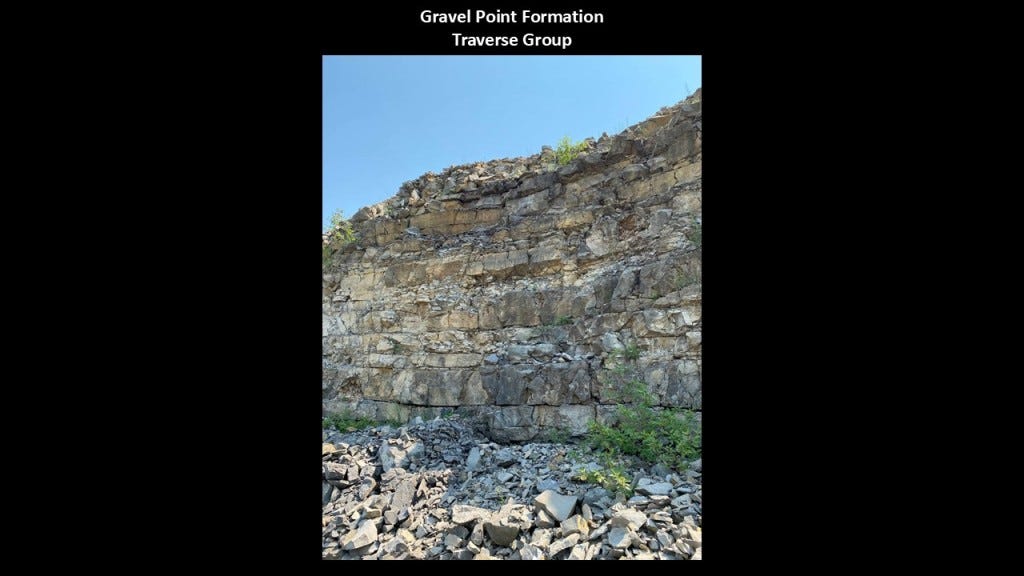

We are told that Petoskey stones are a petrified genus of colonial rugose coral that turned into limestone, and is found in limestone rock formations dating back to the Devonian period 350-million years ago, and can be found in most of the rock formations of the Traverse Group in Michigan.

The Traverse Group outcrops are in Emmet and Charlevoix Counties where we have been looking so far, and can be viewed by travelling the Michigan portion of US Highway 31 along the Lake Michigan shoreline.

We are told that the Traverse Group formed as a shallow carbonate shelf during the Devonian period when the most recent supercontinent, Pangaea, was beginning to take shape.

There are several points I would like to bring forward from what I am seeing here.

First, I don’t believe what the historical narrative tells us about geological processes over long periods of time being responsible for what we see in the world today.

Like I said earlier in this post, I believe all along the Earth’s coastlines there are submerged landmasses and ruined land from this recent cataclysmic event which destroyed the Earth’s original energy grid, along with creating land features like estuaries. wetlands, deserts and dunes.

This belief is at odds with the official explanation, which is that of a worldwide Great sea level rise as a result of melting glaciers from the last Ice Age and the expansion of seawater as it warms, and both are due to global warming.

The basis of the belief in Ice Ages in our modern scientific paradigms come from Sir Charles Lyell, who published “The Principles of Geology” in three volumes between 1830 and 1833.

In these books, Lyell presented the idea that the Earth was shaped by the same natural processes that are still operating today at similar intensities, and as such a proponent of “Uniformitarianism,” a gradualistic view of natural laws and processes occurring at the same rate now as they have always done.

As a result of Lyell’s work, the glacial theory gained acceptance between 1839 and 1846, and we are told during that time, scientists started to recognize the existence of ice ages, and do to this day.

Sir Charles Lyell’s books on “Uniformitarianism” and “Ice Ages” in geology became the only accepted model taught by Academia.

The issue is contrast to the view of Catastrophism, the belief that changes in the Earth’s crust have resulted primarily from sudden violent and unusual events.

The Academic world supports Uniformitarianism without question as the only explanation for what we see in today’s world.

So let’s take a look at several data points to consider in trying to unravel a different perspective from what is found in Michigan on what might have taken place because I really don’t believe it is what we have always been told.

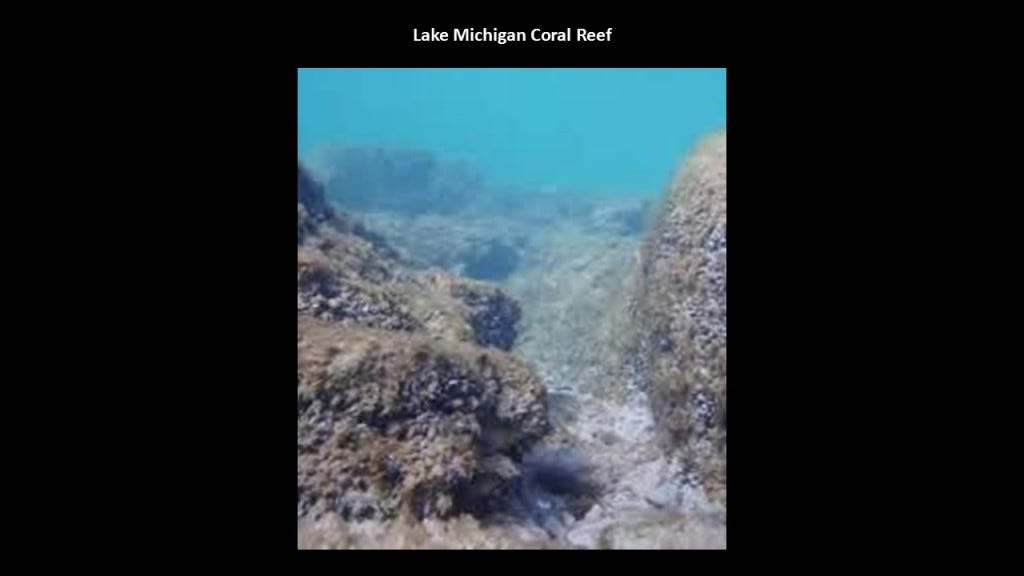

First, we are told that Petoskey stones are leftover fragments of the many coral reefs that existed in warm-water seas from Charlevoix to Alpena some 300 million years ago, where we see “barrier reefs” and “pinnacle reefs” across the Lower Peninsula of Michigan.

Barrier Reefs are said to occur in the shallowest of water, and are a continuous near shore feature.

Pinnacle Reefs are said to form in deeper water, as isolated “pinnacles” of coral.

A coral reef is defined as an underwater ecosystem built by reef-building corals, typically in shallow waters, though on smaller scales in other areas, like deeper waters.

Coral reefs are frequently found on things like sunken ships, like the tugboat John Evenson, which sank in 1884, and was found at a depth of 42-feet, or 13-meters, near Algoma, Wisconsin.

Wouldn’t it stand to reason that coral reefs would form on sunken buildings and other sunken infrastructure as well?

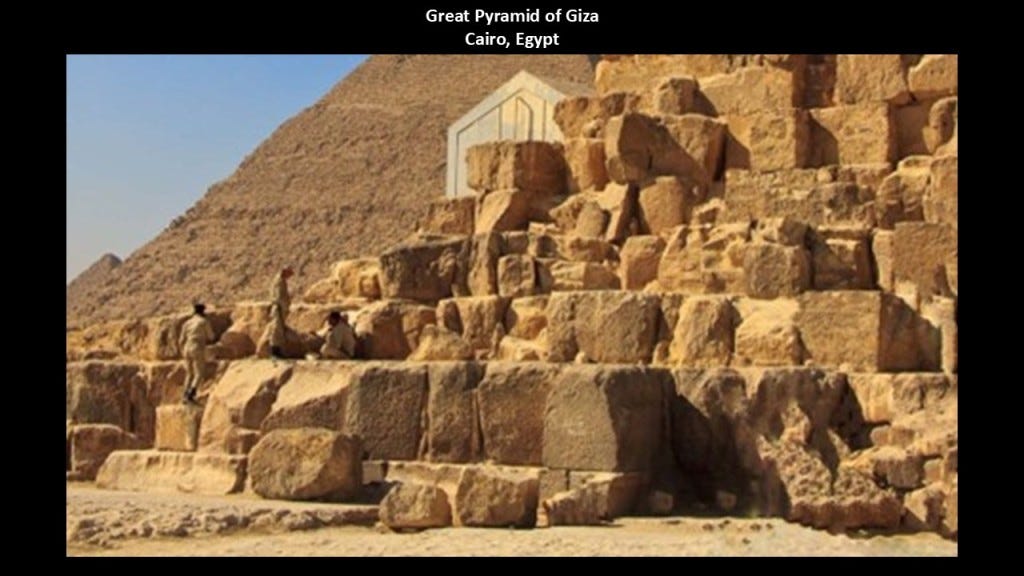

I also want to point out that limestone was a common building material in the ancient world, and used in constructions like the Pyramids of Giza…

…and the Western Wall, also known as the “Wailing Wall,” an ancient limestone wall in the old city of Jerusalem.

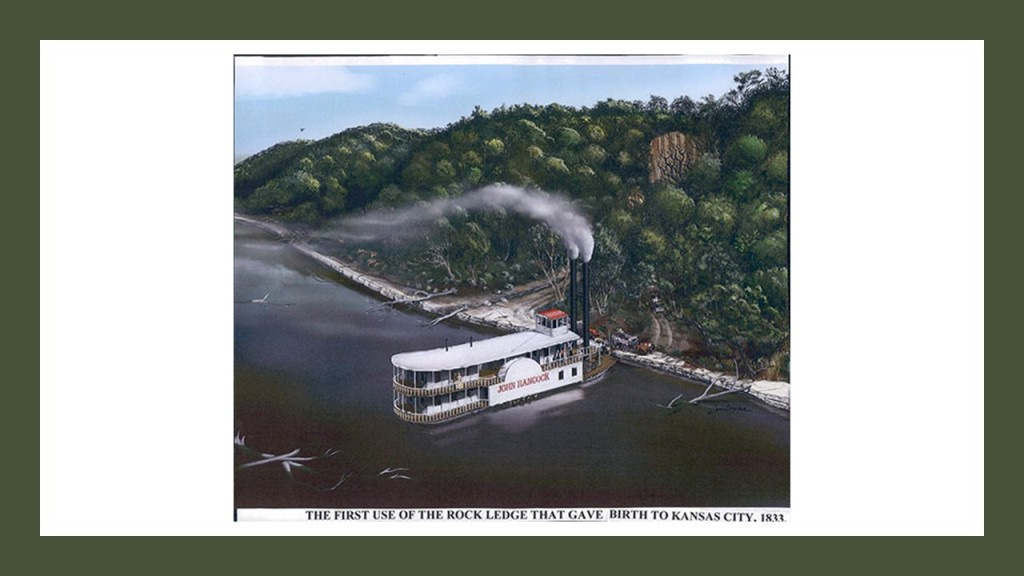

In other places in the early history of the United States, we are told that a rock ledge became the landing place for riverboats and wagon trains starting in 1833, on the southside of the Missouri River at what became Kansas City, Missouri.

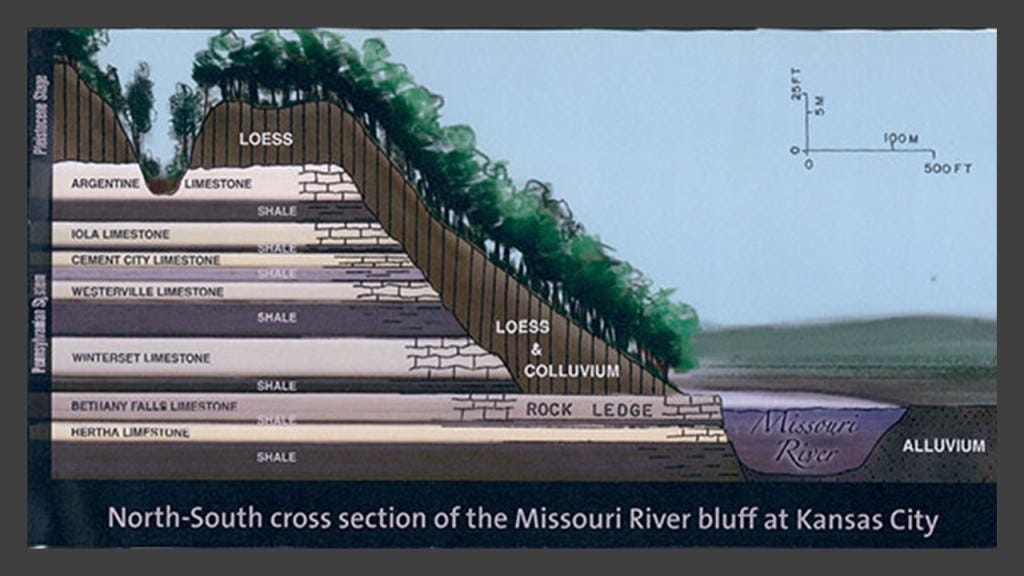

And all of these strata of limestone underneath the surface were identified where this particular rock ledge was located.

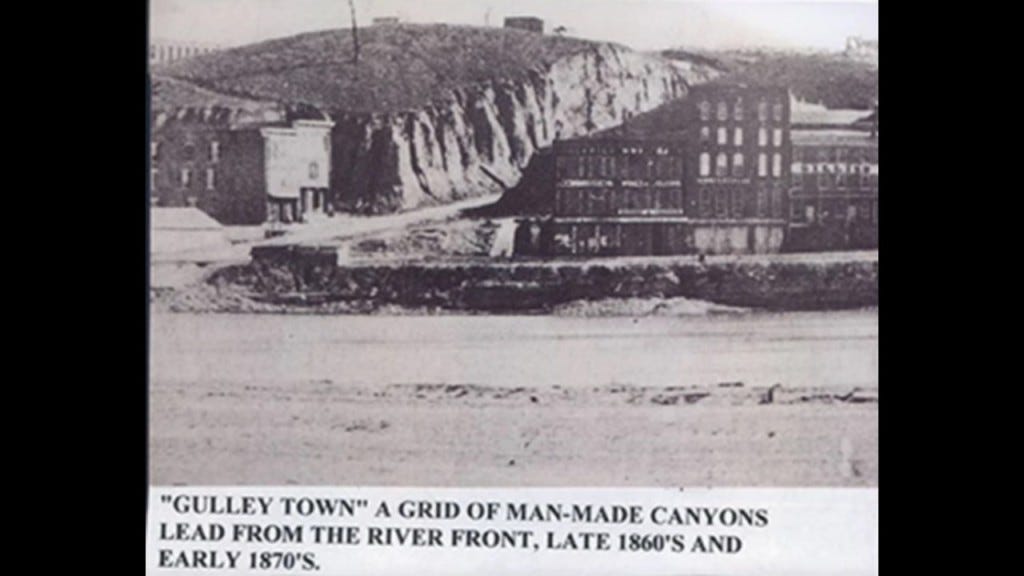

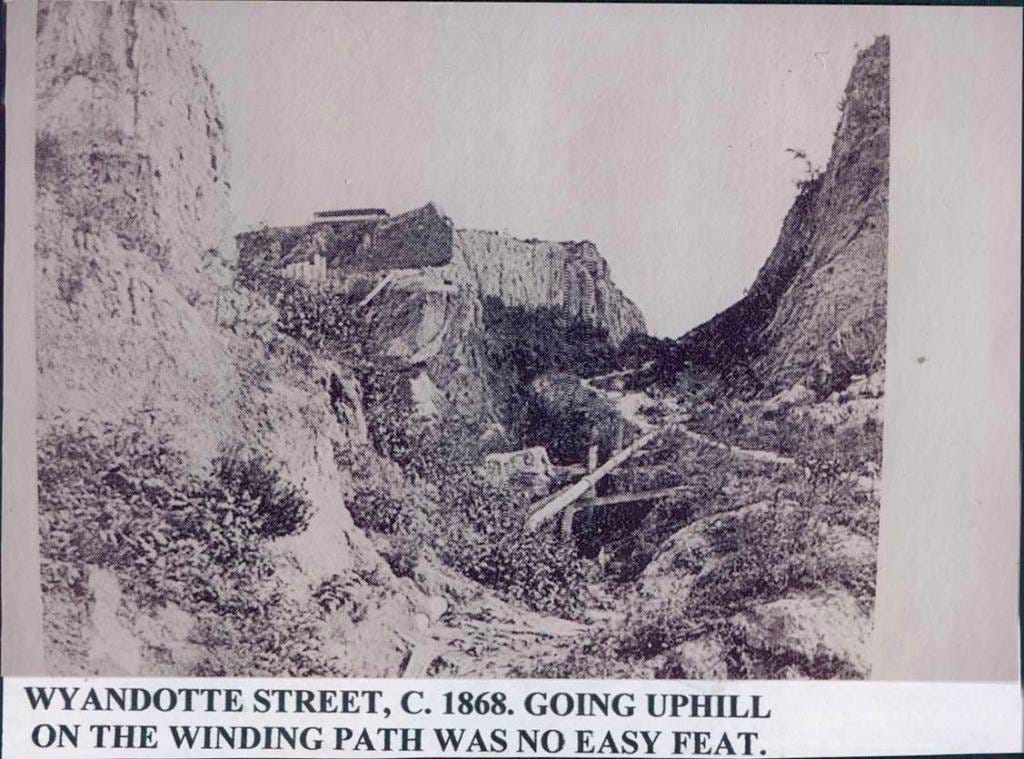

Other historic pictures that I would like to include of Kansas City, Missouri, that are very interesting, and tell a completely different story than what our historical narrative tells us about this time period in our history include this one of when it was called “Gulley Town” in the 1860s and 1870s, where it looks like it was buried and needed to be dug out.

I also found these views of Wyandotte Street in Kansas City, Missouri, as it looked in 1868…

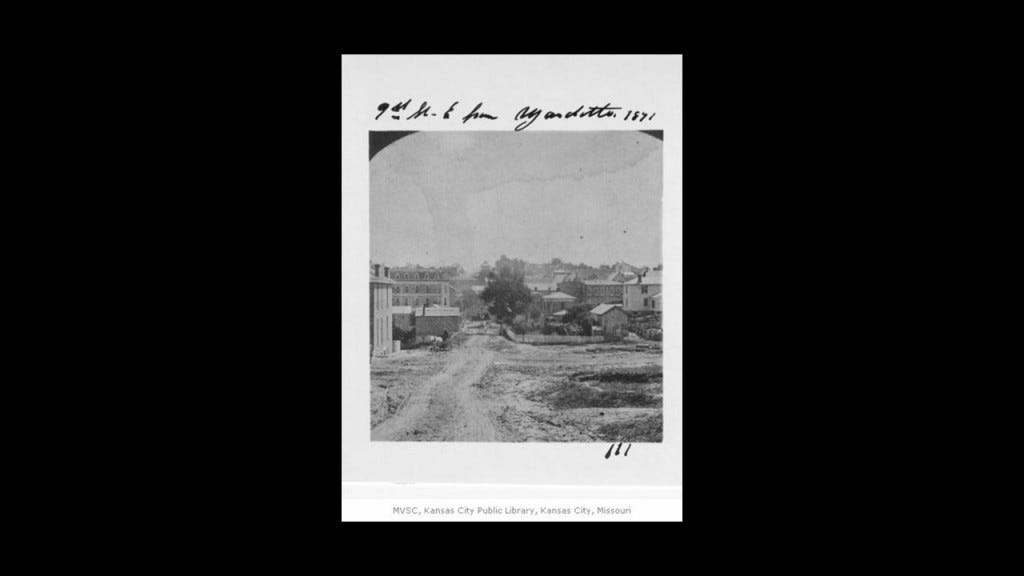

…in 1870…

…in 1871…

…and here are historic photos of some of the buildings on Wyandotte Street circa 1928.

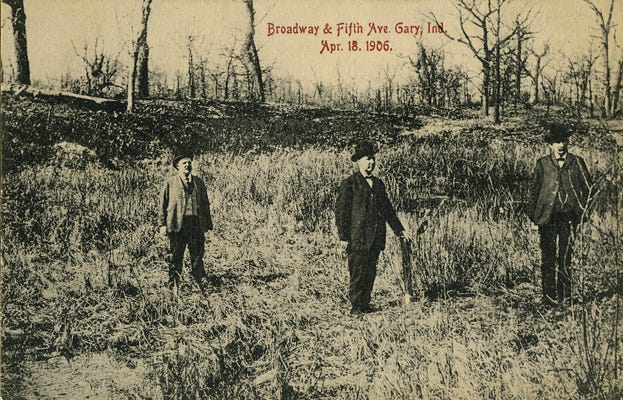

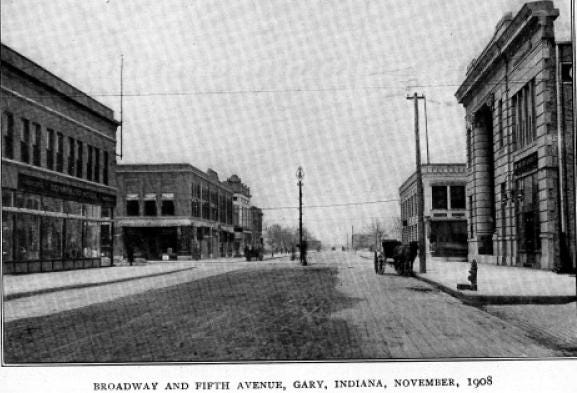

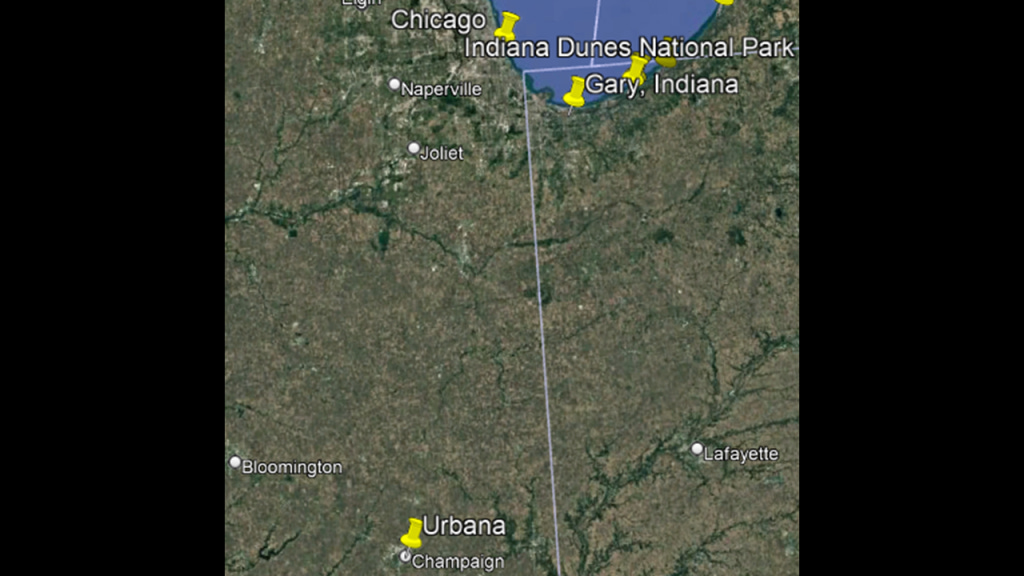

We are going to see this same scenario again of digging-out infrastructure when we come to Gary in Indiana on the southern shore of Lake Michigan.

Next, Grand Traverse Bay is on the other side of Charlevoix from Petoskey, and a short-distance south of Beaver Island.

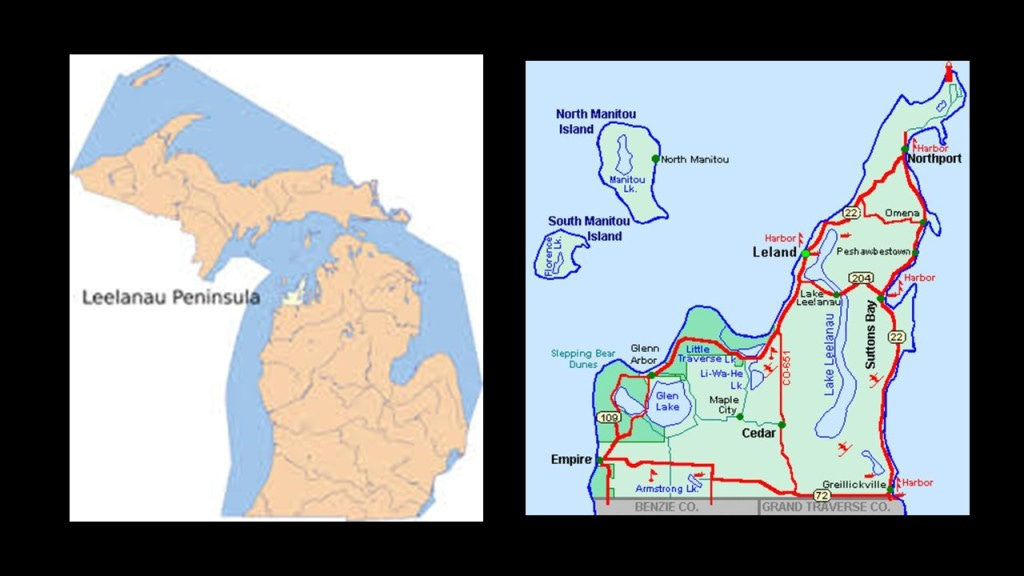

The Grand Traverse Bay is separated from Lake Michigan by the Leelanau Peninsula, also known as the “Little Finger” of the mitten-shaped Lower Peninsula.

The Grand Traverse Lighthouse is located at the tip of the Leelanau Peninsula, where the Manitou Passage separates Lake Michigan and Grand Traverse Bay.

The current lighthouse was said to have been built in 1858, and is located today in Leelanau State Park.

The Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore is located on the western-side of the Leelanau Peninsula, and North and South Manitou Islands, and is also notable for its shipwrecks, so much so the bottomlands have been designated the “Manitou Passage Underwater Preserve.”

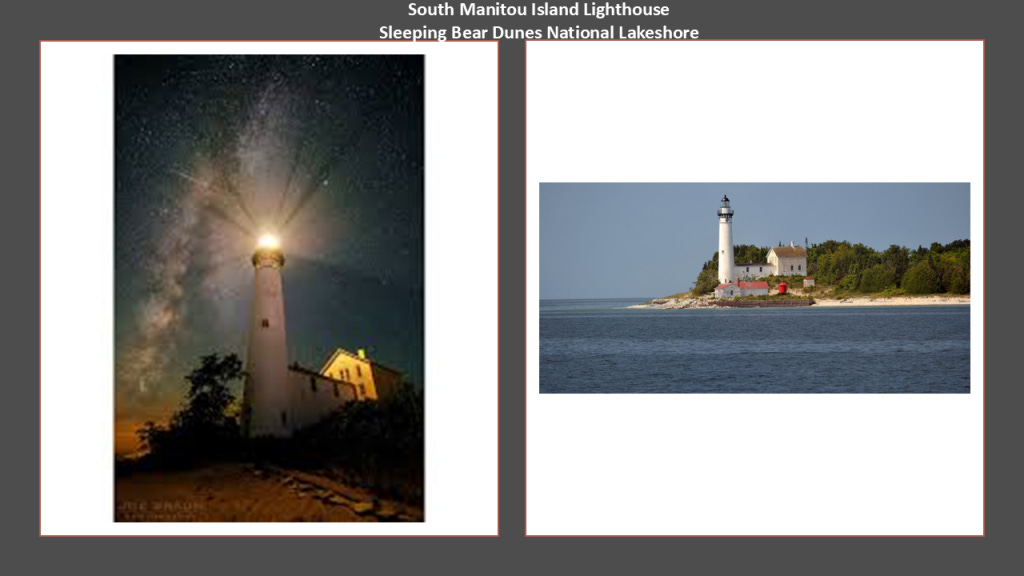

There is also a lighthouse on South Manitou Island, with the current one said to have been built in 1872, and decommissioned in 1958.

It is a museum these days.

The North Manitou Shoal Light is located southeast of North Manitou Island, and it was said to have been constructed in 1935 to mark a dangerous shoal, and it is still in operation today.

A shoal is defined as a place where a body of water is shallow, and where a ridge, bank or bar is close to the surface of the water, and poses a danger to navigation.

In the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore on the Leelanau Peninsula, there are such places to visit and hike as Pyramid Point, known for its stunning views of Lake Michigan and the Manitou Islands…

…the Empire Bluff Trail…

…and the Pierce Stocking Scenic Drive, a 7.4-mile, or 11.9-kilometer, drive through forest and dune areas and great views of Lake Michigan.

It was said to have been built in the 1960s and finished in 1967 by a lumberman named Pierce Stocking who wanted to share the beauty of the area with others.

The Grand Traverse Bay is further divided into an “East Arm” and a “West Arm,” which are separated by what is called the “Old Mission Peninsula.”

The Old Mission Peninsula has the Mission Point Lighthouse at its northern tip, which lies just a few yards south of the 45th Parallel North, which is halfway between the North Pole and the Equator.

The Mission Point Lighthouse was said to have been built in 1870, and it was deactivated in 1933.

It is in Lighthouse Park, and accessible to the public.

Traverse City is located at the base of the Old Mission Peninsula, and is the largest city in northern Michigan.

Traverse City is nicknamed “The Cherry Capital of the World,” and the whole Grand Traverse Bay region is known for its cherry production and its wine-grape-growing and Michigan wine.

There are several things I would like to mention about this area.

First is that prior to European settlement, we are told the Ottawa people were prevalent here, though it was said to be part of the territory of the Council of Three Fires, an alliance of the Anishinaabe peoples of Ottawa, Ojibway, and Potawatomi.

Before the arrival of western Europeans, this land was inhabited collectively by the Anishinaabe, meaning something along the lines of “original people” in their Algonquin language.

When I searched for a map of where the Algonquin-speaking peoples lived in North America, and this is what comes up, with their lands covering a vast section of it.

While the Algonquin language has not died out completely in North America, it is already extinct in many places, and highly-endangered in general.

For one example of many, Pequot – Mohegan was an Algonquin-language spoken by the Mohegan, Pequot, and Niantic people of southern New England, and the Montaukett and Shinnecock of Long Island, and what we are told is that it did not have a writing system, and that the only significant writings came from European colonizers who interacted with speakers of the language.

The last living speaker of this language died sometime around 1900.

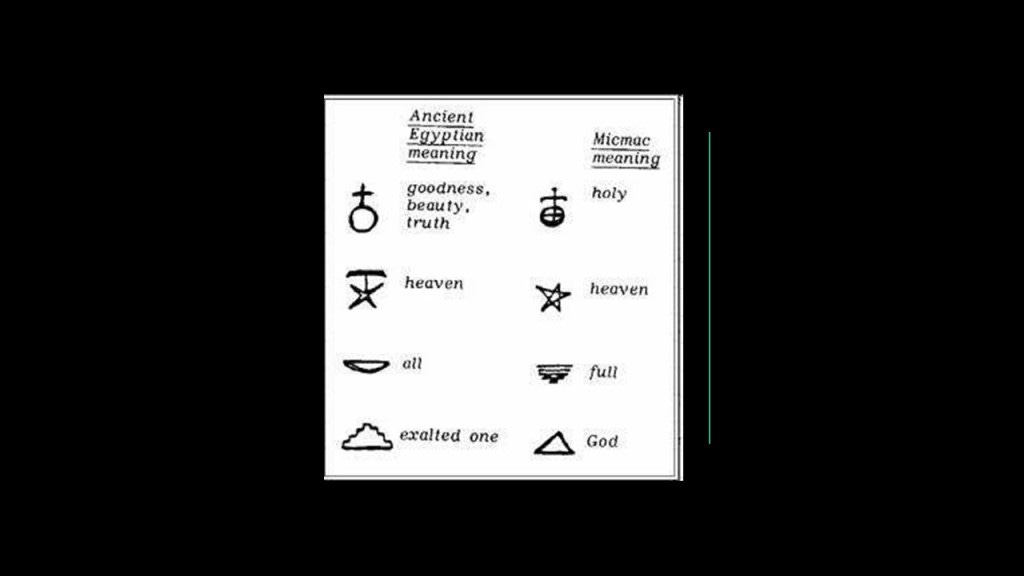

There is something interesting to note about the Algonquin language.

It is extremely hard to find this kind of information because of the hunter-gatherer theme going on with indigenous peoples of North America in the narrative, but I found an example in the written language script of the Algonquin Mikmaq people of Nova Scotia, and it is that of an apparent connection to the Egyptian language script.

We are told that what became Traverse City was first settled in June of 1847 by Captain Horace Boardman, who built a sawmill near the mouth of the Boardman River.

Traverse City was incorporated as a village in 1881, and as a city in 1895.

According to our historical narrative, the railroad arrived in Traverse City in December of 1872 with the Traverse City Railroad Company Spur from the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad Line from Walton Junction, and by 1890, there were at least three more railroad lines serving the Traverse City region.

Today the historic Traverse City railroad station is the Filling Station Microbrewery, with the Cherry Capital Airport nearby.

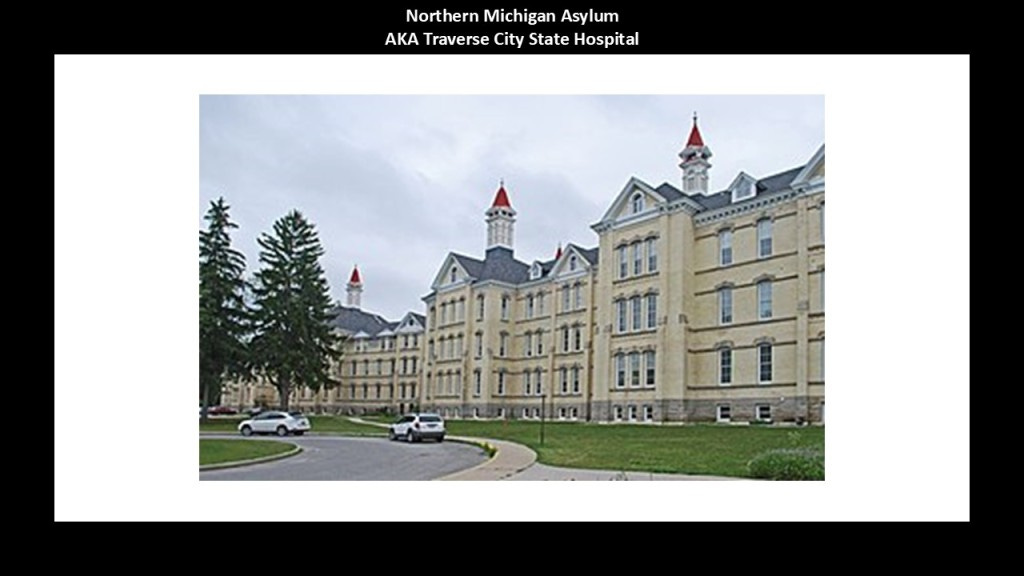

In 1881, the Northern Michigan Asylum, later known as the Traverse City State Hospital, was established here as a Kirkbride facility, and first opened in 1885 with 43 residents, and we are told that between 1885 and 1924 under its superintendent James Decker Munson, it expanded and became the city’s largest employer at one time.

It closed its doors as a State Hospital in 1989.

In 1854, Dr. Thomas S. Kirkbride first published what was considered the source book in the 19th-century for Psychiatric Directives entitled “On the Construction, Organization, and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane, ” with some remarks on insanity and its treatment.

We are told that throughout the 19th-century, numerous psychiatric hospitals were designed and constructed according to the Kirkbride Plan across the U. S. and while numerous Kirkbride structures still exist, many have been demolished, partially-demolished, or repurposed.

So, today the former Northern Michigan Asylum Kirkbride facility is being redeveloped as a multi-use facility after years of sitting abandoned…

…though it also has a reputation of being haunted, which is more typical than not of these places.

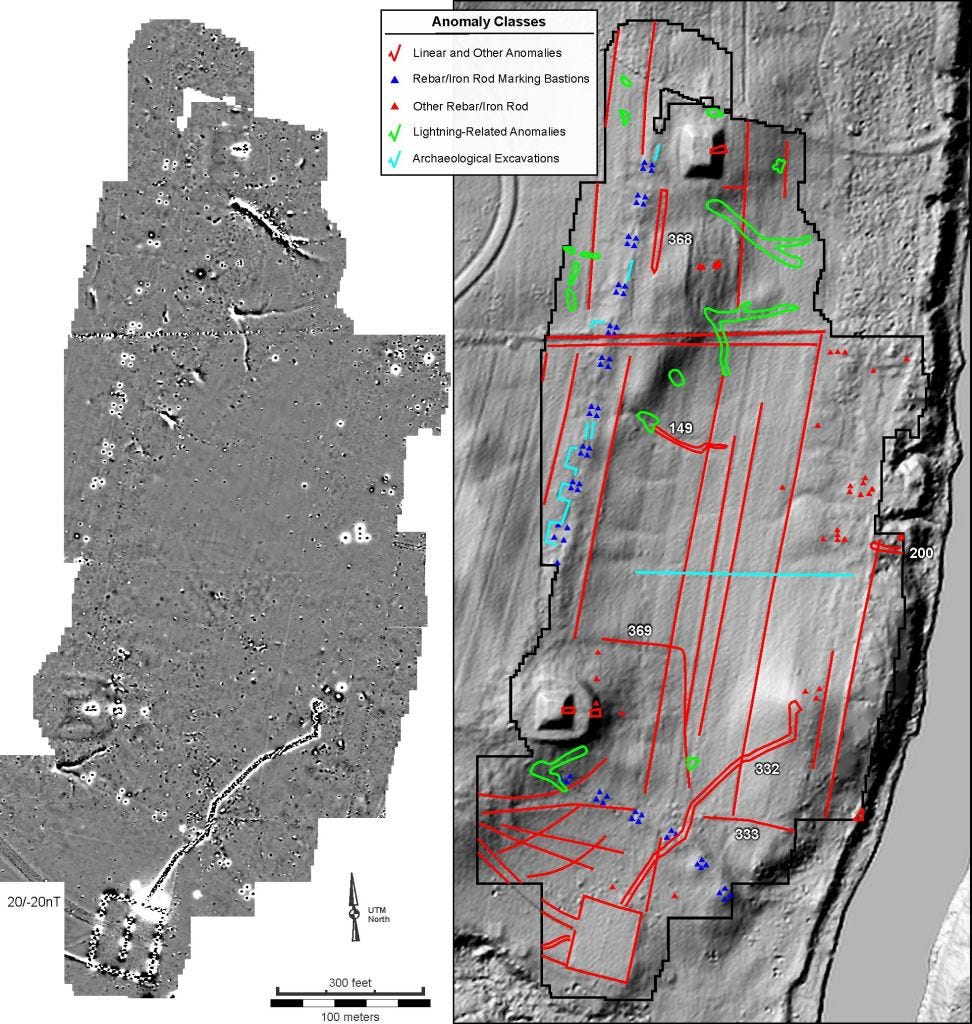

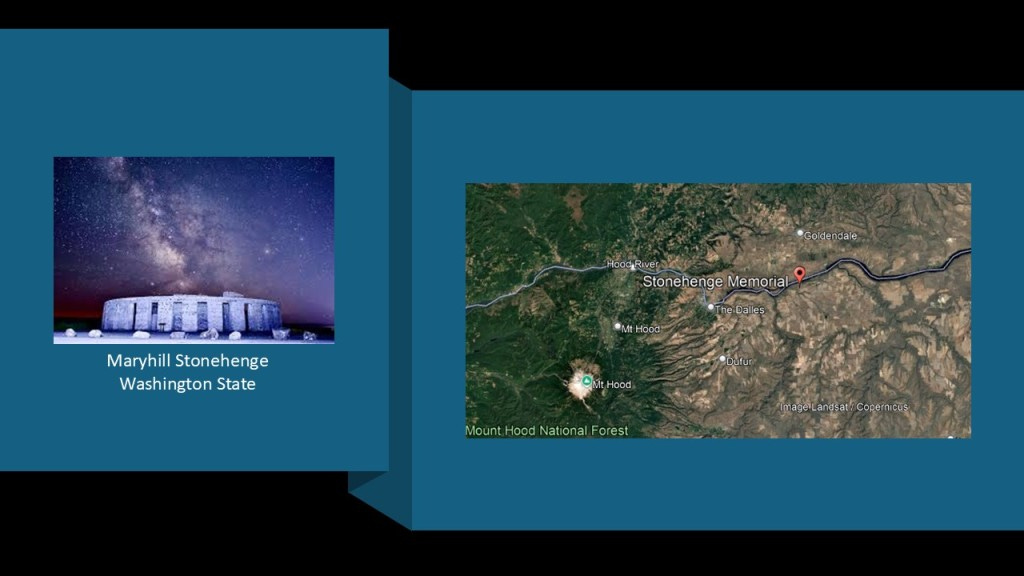

Before I take leave of the Grand Traverse Bay region, I would like to mention that there was a stonehenge-type structure identified in the Grand Traverse Bay.

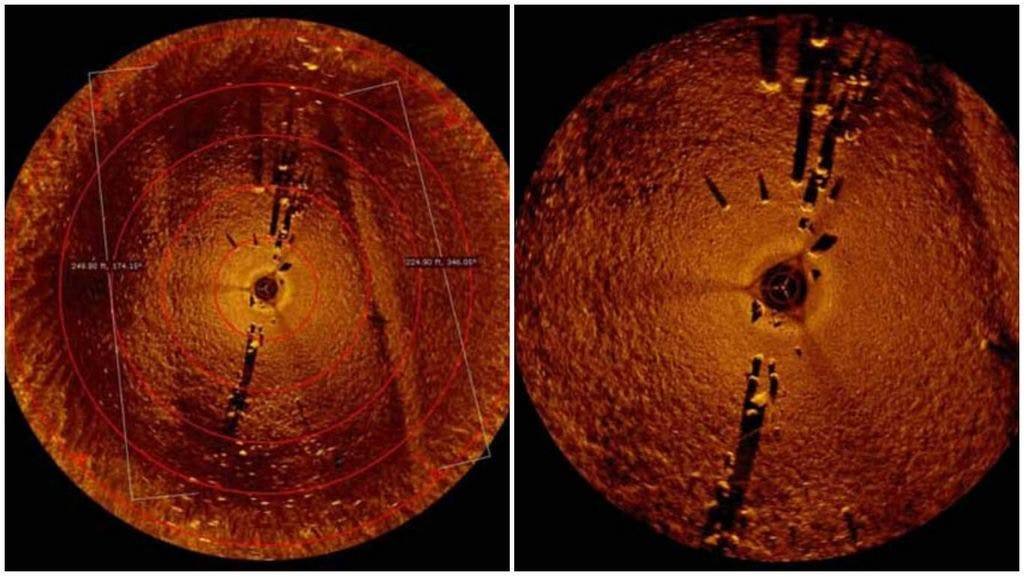

Dr. Mark Holley, Professor of Underwater Archeology at Northwestern Michigan University, discovered an arrangement of large granite stones resting on the lake bed about 40-feet, or 12-meters, below the surface of the water, in 2007.

The stones are believed to date back 9,000-years, which is 4,000-years older than the date given to England’s famous Stonehenge.

One more thing I would like to mention here is US Highway Route 31, which runs along the western portion of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan from Bertrand Township in Berrien County at the state line with Indiana to its terminus on I-75 south of Mackinaw City.

I will be looking primarily at this part of the state of Michigan along US-31 as I go down the eastern coast of Lake Michigan.

US Highway Route 31 is a major North-South Highway that runs from Spanish Fort in Alabama at the Junction of US-90 & US-98.

I find all the major long-distance highways or interstates noteworthy that I have come across so far in the Great Lakes region.

The first was Minnesota State Highway 61, formerly known as the “North Shore Highway” and which is now known as the “North Shore Scenic Drive.”

Until 1991 Minnesota State Highway 61 was part of United States Highway 61 from 1926 to 1991.

The full-length of US-61 runs from its southern terminus in New Orleans, Louisiana, to its northern terminus at Wyoming, Minnesota.

It is considered the “Great River Road,” a collection of state and local roads that follow the course of the Mississippi River in ten states.

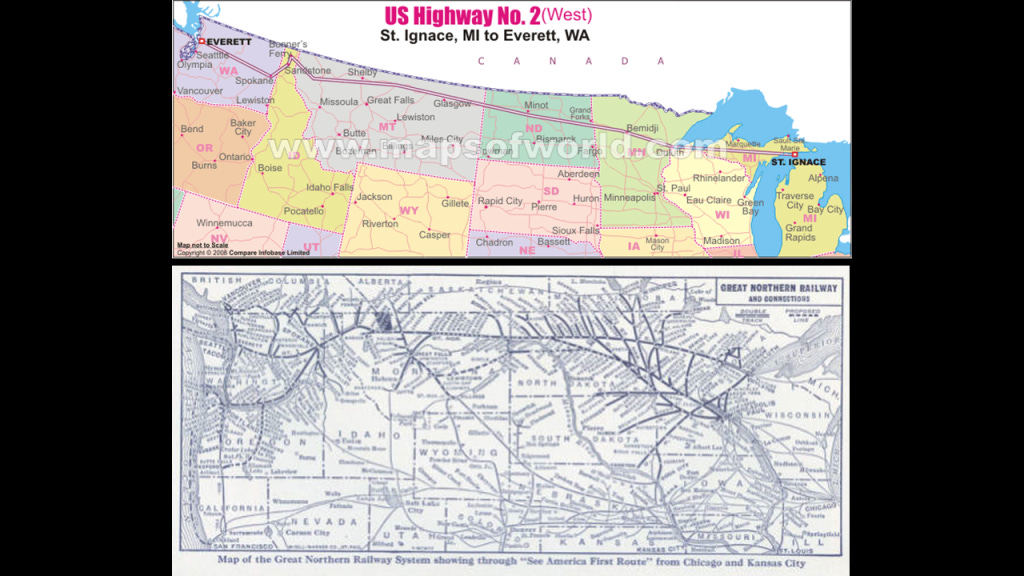

Then US Highway Route 2, which consists of two segments, and is the northernmost East-West highway in the United States.

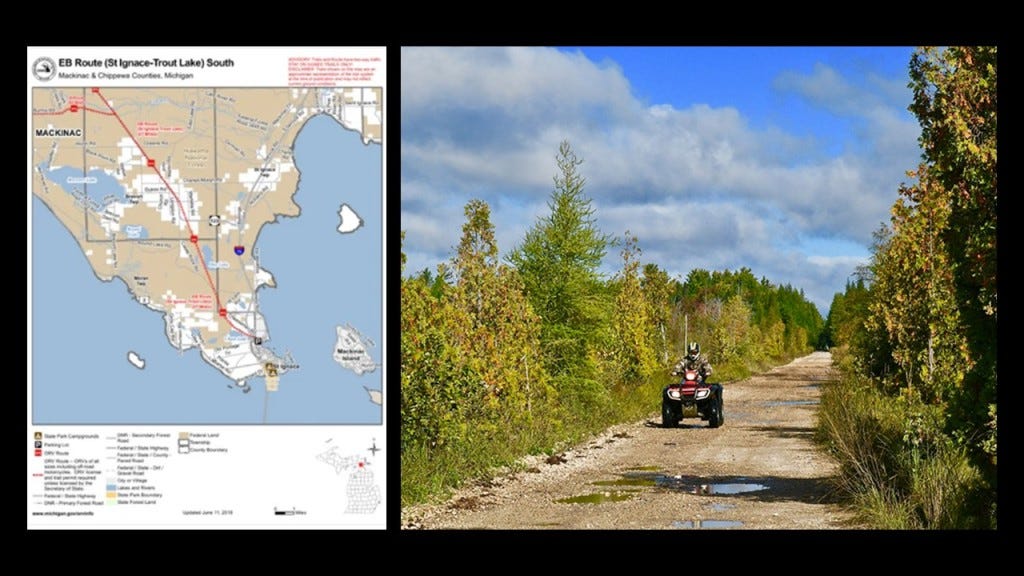

The western segment begins at an interchange with Interstate-5 in Everett, Washington, and ends at Interstate-75 in St. Ignace, Michigan.

The eastern segment of US-2 begins at US-11 at Rouses Point, New York, and ends in Houlton, Maine, at Interstate-95.

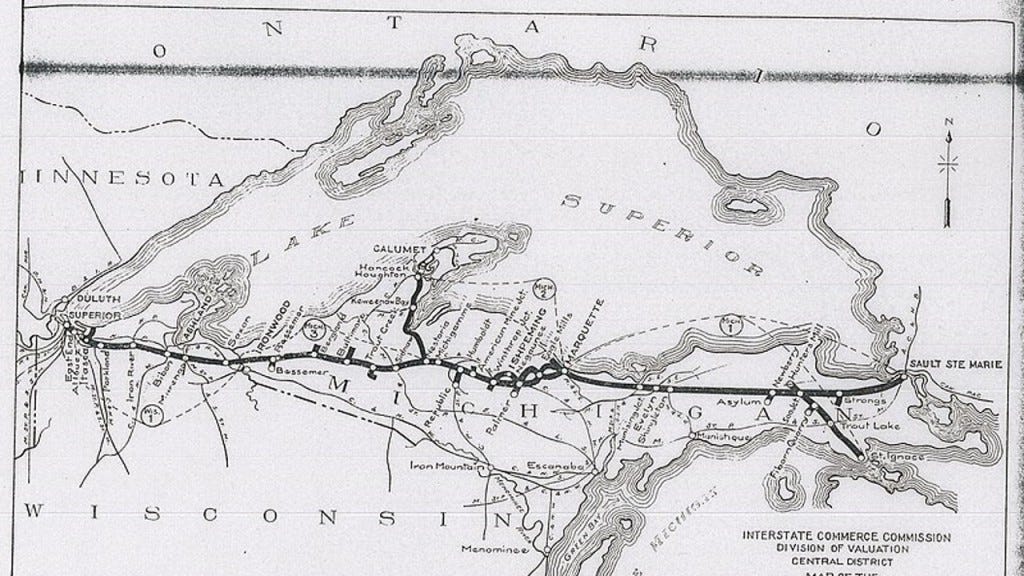

The western segment of US-2 goes west from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and roughly parallels the historical Great Northern Railway.

Then there’s US Highway Route 41 between Miami, Florida, and the tip of Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula at Copper Harbor…

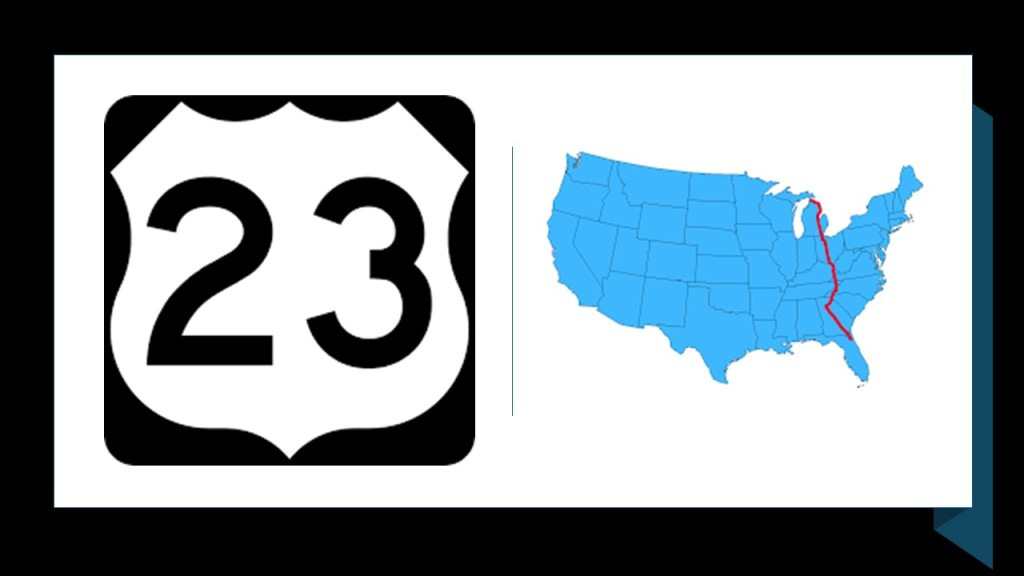

…U. S. Highway 23, a major North – South U. S. Highway between Jacksonville, Florida, and Mackinaw City, Michigan at I-75…

…and the northern terminus of Interstate 75 is Sault Ste. Marie in Michigan, which also goes all the way to Miami, Florida, at its southern terminus.

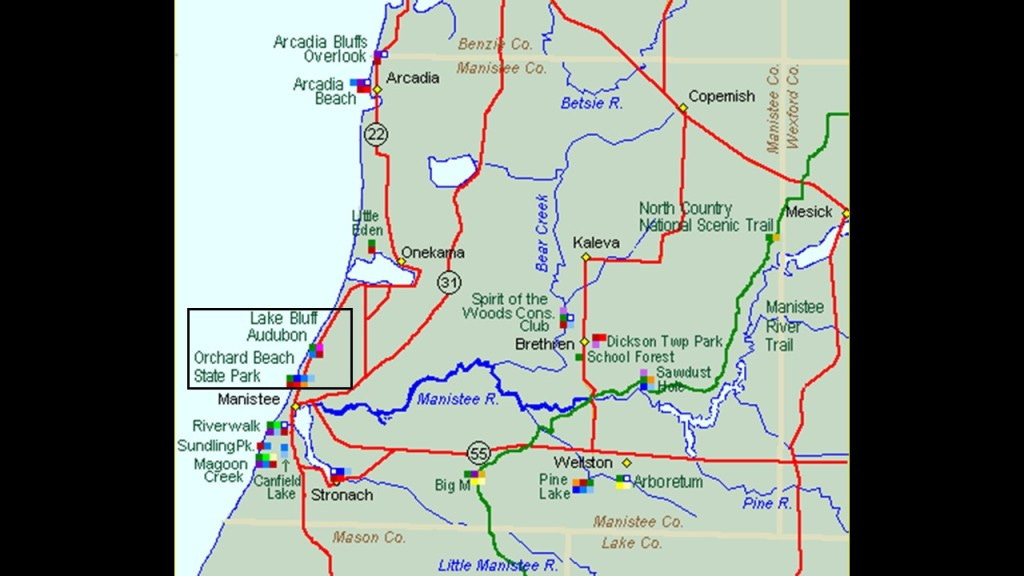

The next place I am to take a look at moving down the coast of the eastern shore of Lake Michigan is Manistee.

Like Charlevoix, the city of Manistee is located on an isthmus, in this case between Manistee Lake and Lake Michigan, with the Manistee River going through the city.

It is located on US-31.

We are told that a Jesuit mission was first established in Manistee in 1751, and that Jesuit missionaries came to the area in the early 19th-century, with a Jesuit Mission house located on the northwest shore of Manistee Lake in 1826.

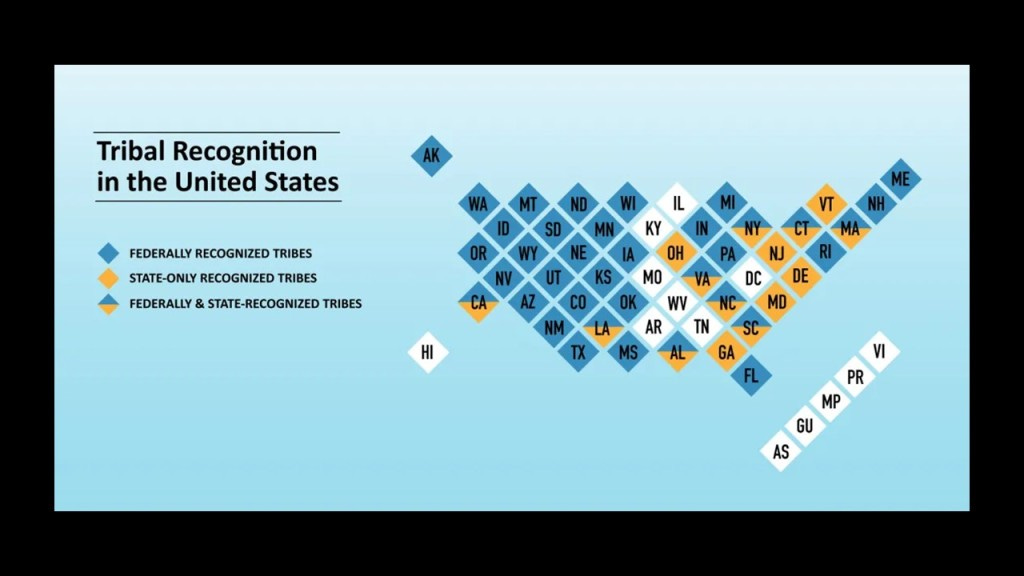

According to available information, Manistee was one of fifteen Ottawa villages on Lake Michigan’s shore in 1830, and it is the location of the federally-recognized Little River Band of Ottawa, who historically lived in this region.

Federal recognition signifies the United States Government’s acknowledgment of a tribe’s status as a sovereign entity with a government-to-government relationship.

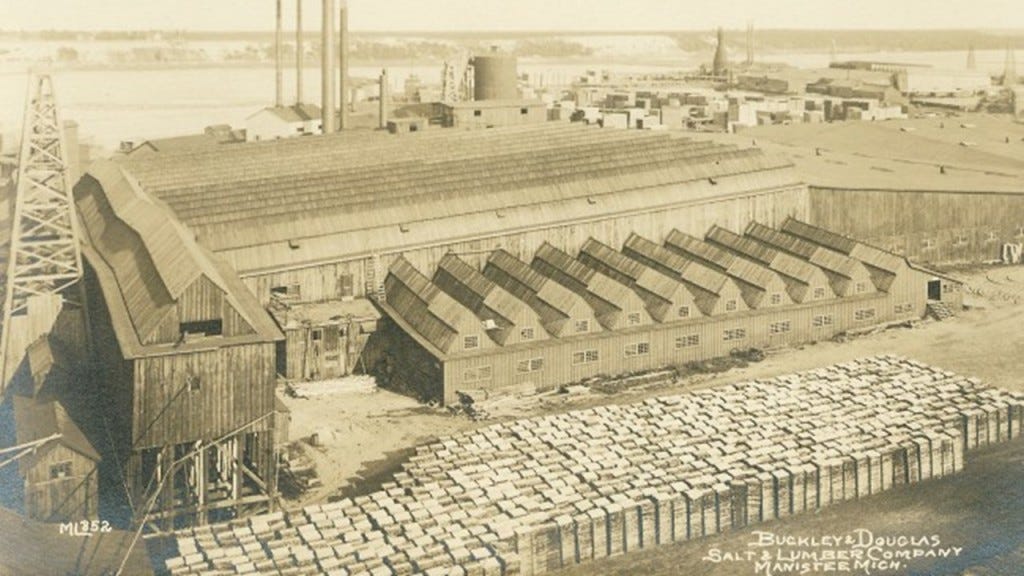

The first European settlement here happened in Manistee in April of 1841, when settlers John and Adam Stronach arrived with men and equipment and established a sawmill, and Manistee became a significant location for lumber mills, with large numbers of white pine logs being floated down the river to the port at Manistee.

I will be talking about the Great Fires of October 8th and 9th of 1871 in this series.

The Manistee Fire was one of the fires that constitute what is known as the “Great Michigan Fire” of October 8th of 1871, along with the Holland Fire and the Port Huron Fire.

I will be looking at the city of Holland in this post, and Port Huron in the next post on Lake Huron.

These fires took place on the exact same day as the Great Chicago Fire and Peshtigo Fire, and Urbana in Illinois burned on the following day, all of which I will be talking about here.

We are told the Manistee Fire destroyed much of the city of Manistee.

The city of Manistee wasn’t incorporated until 1882, 11-years after the Great Fire, and then this is the Manistee Fire Department, said to be the oldest continuously manned fire station in the world.

Interesting to note that this fire station was said to have been built in 1888, seventeen years after the Manistee fire of 1871.

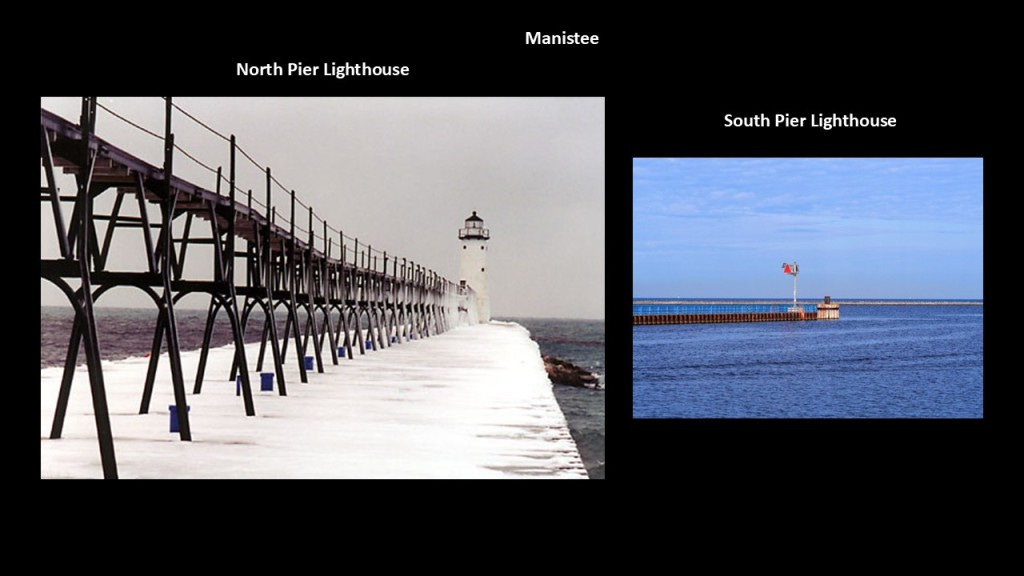

Manistee Harbor still has two active lighthouses, one on its North Pier and one on its South Pier, which are also called “breakwaters.”

We are told that the first lighthouse was on the South Pier in 1870, but it burned in the Great Fire in 1871.

Then we are told two lighthouses were built here in 1875, but over the years they have been moved, and even torn down and rebuilt.

Here is a photo of the North Pier Lighthouse in Manistee in alignment with the setting sun.

There are two other places I would like to look at in the Manistee area before I move south from here on the coast to Ludington.

Those places are the Orchard Beach State Park and the Lake Bluff Bird Sanctuary.

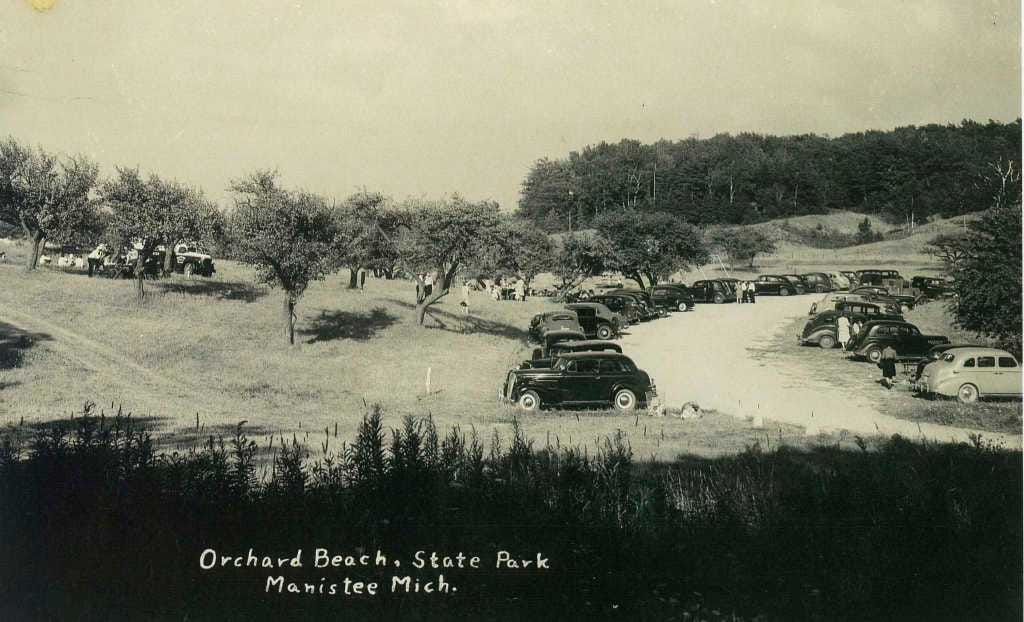

Firstly, Orchard Beach State Park.

Today, it is a public recreation area situated on a bluff just a short-distance north of Manistee.

Apparently there was an apple orchard here that was planted by George Hart some time around 1887, and that by 1892, Hart had built a boardwalk and theater here to attract more tourists.

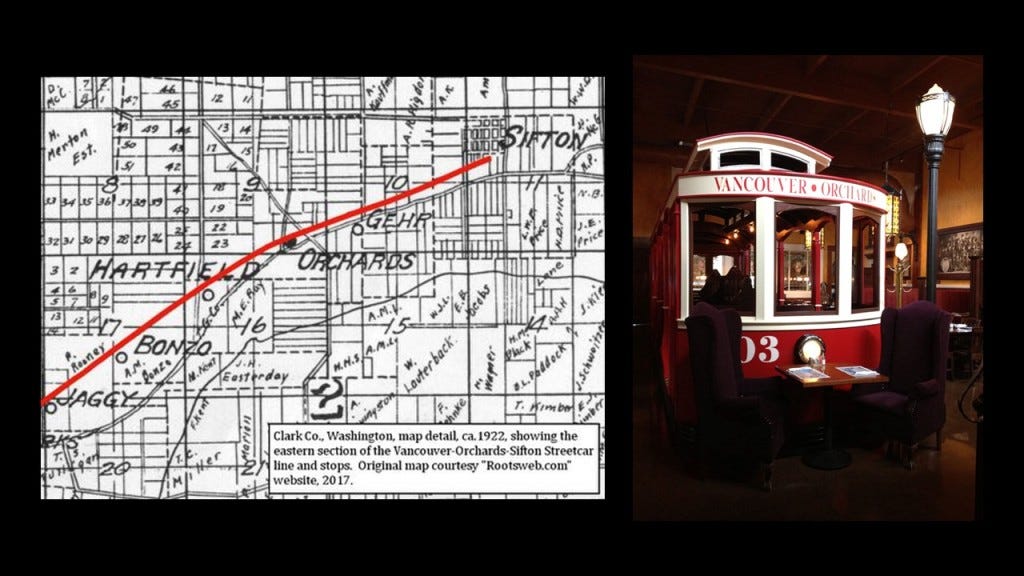

The same year of 1892, trolley service began with the Manistee, Filer, and Eastlake Railway Company and Orchard Beach became a popular beach destination, and that when trolley service was stopped here, the site was purchased by the Manistee Board of Commerce and deeded to the state to become a park in 1921.

Interestingly, in past research I encountered an historical orchard and trolley located together in Vancouver, Washington.

I definitely think there was a connection between the original energy grid and every kind of agriculture.

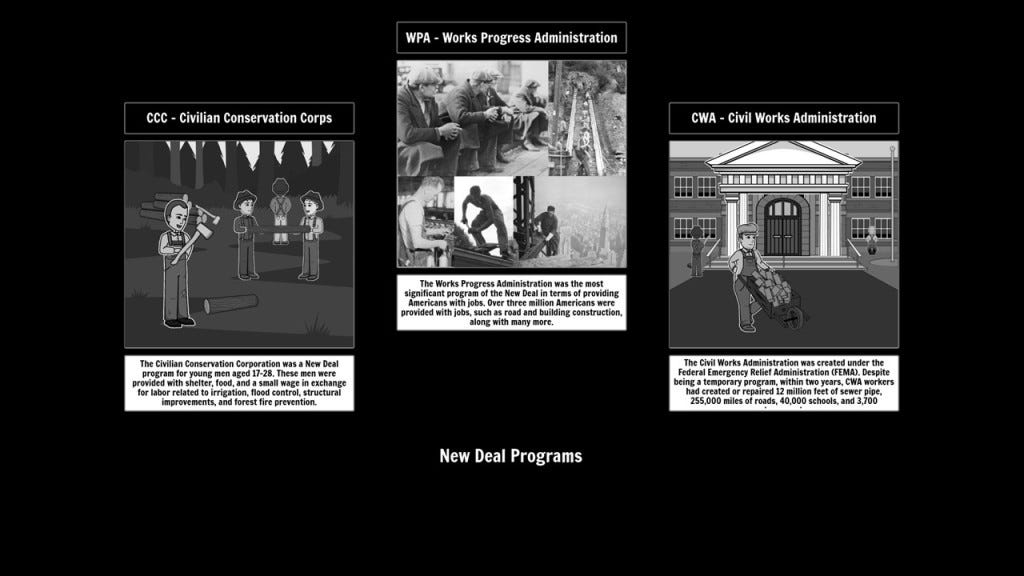

Then, we are told the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was here in the 1930s, and built several limestone structures, including a shelter building.

The 850-ton shelter building pictured here…

…was moved 1,200-feet, or 366-meters, in December of 2020 because the bluff it sat on top of was eroding and unstable.

As I mentioned in this last post about Lake Superior, this is a common finding with lighthouses as well– sitting next to sheared-off, unstable land, and often have to be moved in order to not fall over the side.

An example that comes to mind of this is the Gay Head Lighthouse on Martha’s Vineyard, a small island that is an elite enclave of the very wealthy just off the southern coast of Massachusetts’ Cape Cod.

In 2015, the Gay Head Lighthouse was moved because it was perilously close to the eroding cliff edge.

I consistently find the infrastructure of railroads, lighthouses, star forts, and all manner of the original infrastructure, all being in locations with the same characteristics all over the Earth.

Another example is the “Pacific Surfliner,” an active Amtrak passenger railroad line, that runs along the Pacific Coast of Southern California for 351-miles, or 565-kilometers, from San Diego to San Luis Obispo…

…that is also endangered by crumbling cliffs from coastal erosion, and we are told is under consideration for being moved in-land.

This exact same manifestation of cliffs or bluffs next to bodies of water is found worldwide, looking like land just violently broke off from the landmass.

Here are a few more of countless examples.

The sheer cliffs along the coastline of Hengam Island in the Persian Gulf’s Strait of Hormuz on the top left, compared for similarity of appearance with the sheer white cliffs of Dover on the coast of southern England on the top right, and the cliffs along the southern coast of Australia in Victoria State where the Great Ocean Road runs for a long distance next to a sheer cliff, and showing the location of the 12 Apostles, the name given to what are called “limestone stacks” in the water off Port Campbell.

When the word “sheer” is used to refer to a cliff, it means a high area of land with a very steep side.

One of the meanings of the word “shear” spelled with an “a” is to break off, or be cut off, sharply.

A synonym of the word for “sheer cliff” is “bluff.”

Another meaning of the word “bluff” is a deception, or an attempt to deceive.

Secondly before I leave the Manistee area, I want to look into the Lake Bluff Bird Sanctuary, Located on top of a 100-foot, or 30-meter, -high bluff.

The Michigan Audubon Society received the M. E. and Gertrude Gray home and property as a gift in 1988, which later became the Lake Bluff Bird Sanctuary.

In addition to its status as a bird sanctuary…

…it is notable for the trees preserved on its grounds, which include a Michigan Giant Sequoia…

…and a Michigan Sycamore Maple.

Now I am going to head on down the eastern coast of Lake Michigan to the Ludington area and see what’s there.

The City of Ludington is situated at the mouth of the Pere Marquette River, which quickly turns into the Pere Marquette Lake in Ludington.

We are told that the Jesuit explorer Father Jacques Marquette died near Ludington in 1675, and that in 1955, a memorial and 40-foot, or 12-meter, cross were built to mark the location.

The settlement here was originally named “Pere Marquette,” but was later renamed “Ludington” after the industrialist James Ludington, who established logging operations here.

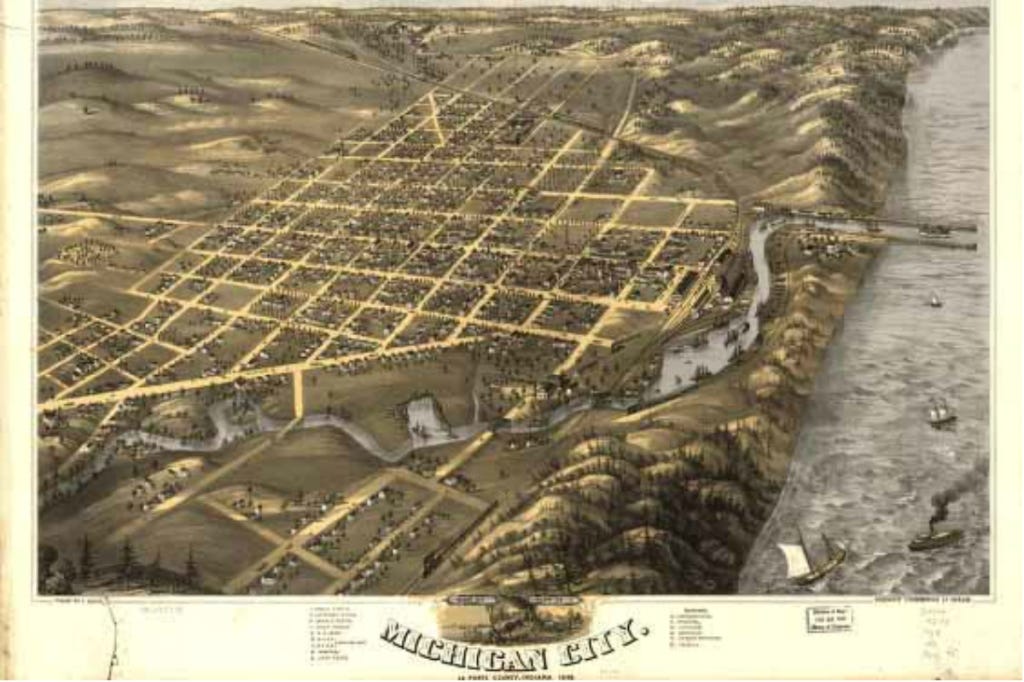

By 1892, Ludington sawmills had produced 162-million board feet of lumber and 52-million wood shingles and Ludington became a major Great Lakes shipping port.

Ludington was incorporated as a city in 1873, and the county seat of Mason County was moved here.

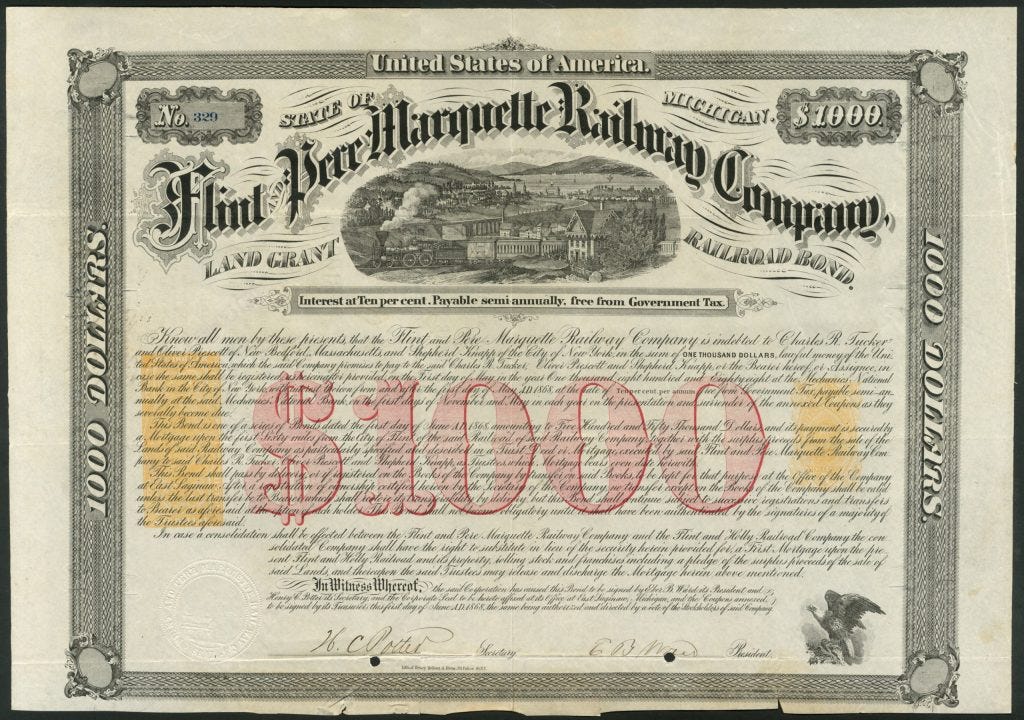

We are told the Flint and Pere Marquette Railroad was chartered in January of 1857 to construct an east-west railway line from Flint in Michigan to Ludington, formerly Pere Marquette, with the railroad completed to that location in 1874.

The Flint and Pere Marquette Railroad began cross-lake shipping operations in 1875 with the sidewheel steamer SS John Sherman to handle freight and then expanded to the larger Goodrich line of steamers.

Then in 1896, this railroad constructed the world’s first steel train ferry, the Pere Marquette, to transport rail cargo across Lake Michigan to Manitowoc in Wisconsin.

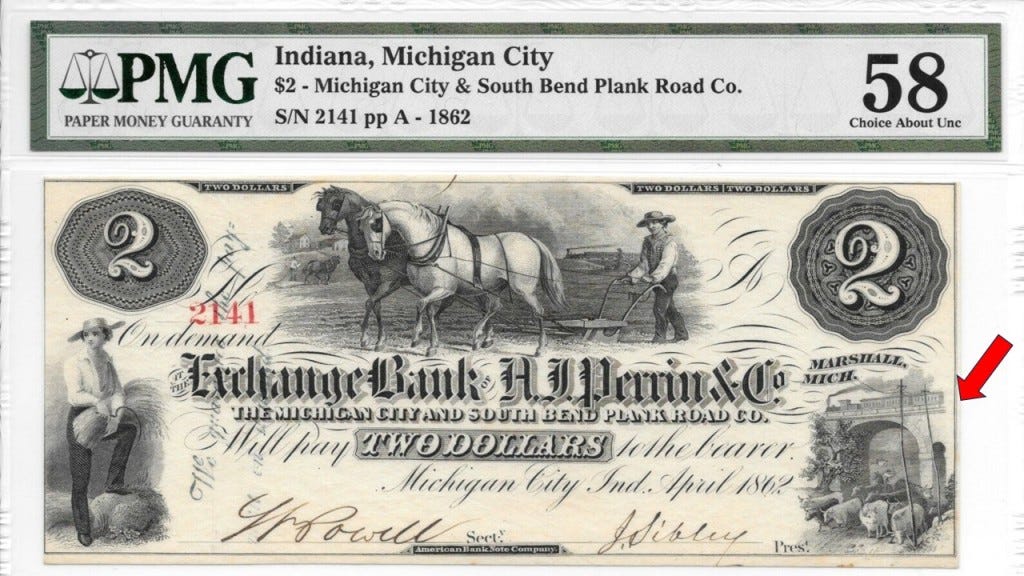

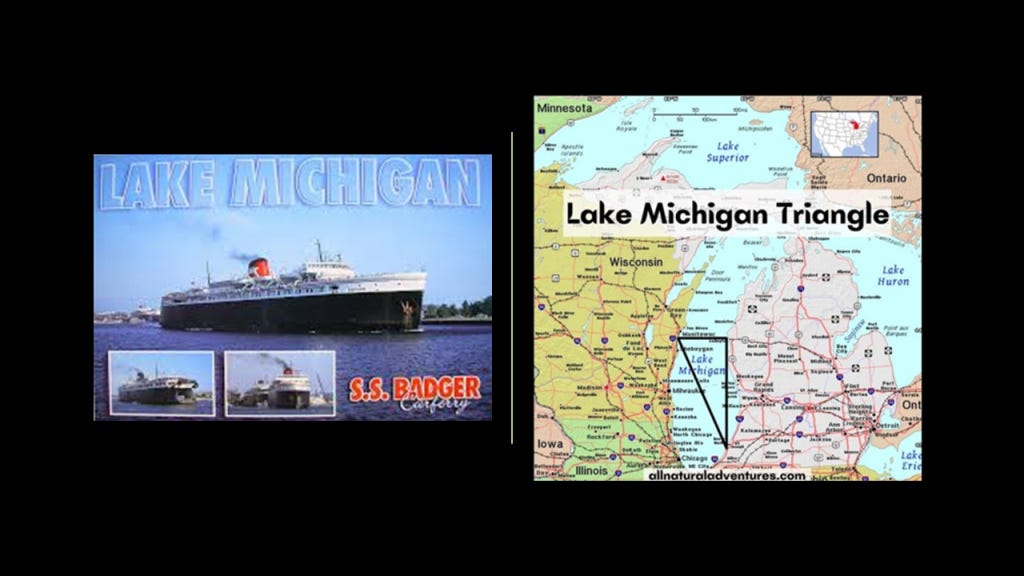

Today, Ludington is the home port of the SS Badger, a vehicle and passenger ferry with daily service in the summer months across Lake Michigan to Manitowoc in Wisconsin, a distance is 62-miles, or 100-kilometers, and the ferry connects US Highway Route 10 as well between these two cities.

The coal-fired SS Badger started out life as a steel train ferry, with a construction date given of 1952, and was retired from that service in November of 1990 as the last railway car ferry service out of not only Ludington, but ending the service on Lake Michigan.

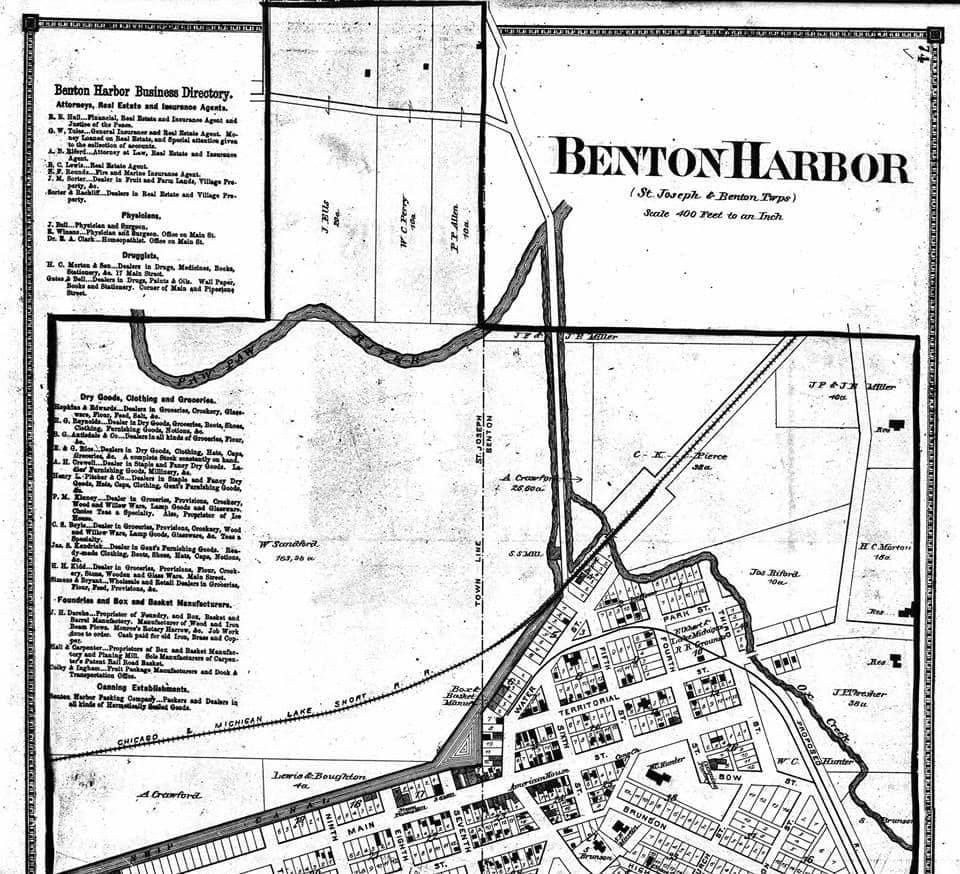

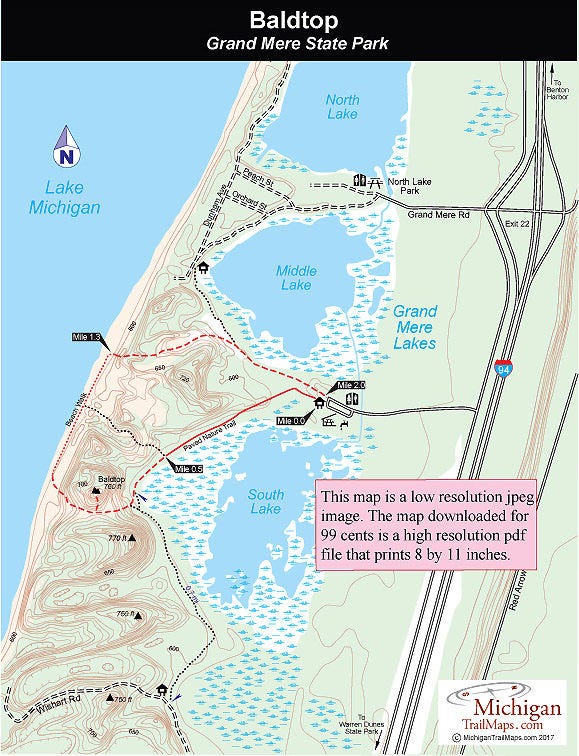

Also interesting to note that the location of the mysterious Lake Michigan Triangle stretches from the three port cities of both Ludington and Manitowoc, and Michigan’s Benton Harbor.

As suggested by the name as a comparison to the Bermuda Triangle, the Michigan Triangle is also a place with a reputation for ships, planes and people disappearing under mysterious circumstances.

The Ludington Lighthouse is located at the end of the North Breakwater where the Pere Marquette River meets Lake Michigan in the Pere Marquette Harbor.

It was said to have been established in 1871 originally, and the structure there today was said to have been built in 1924.

Here is the Ludington Lighthouse in alignment with the setting sun.

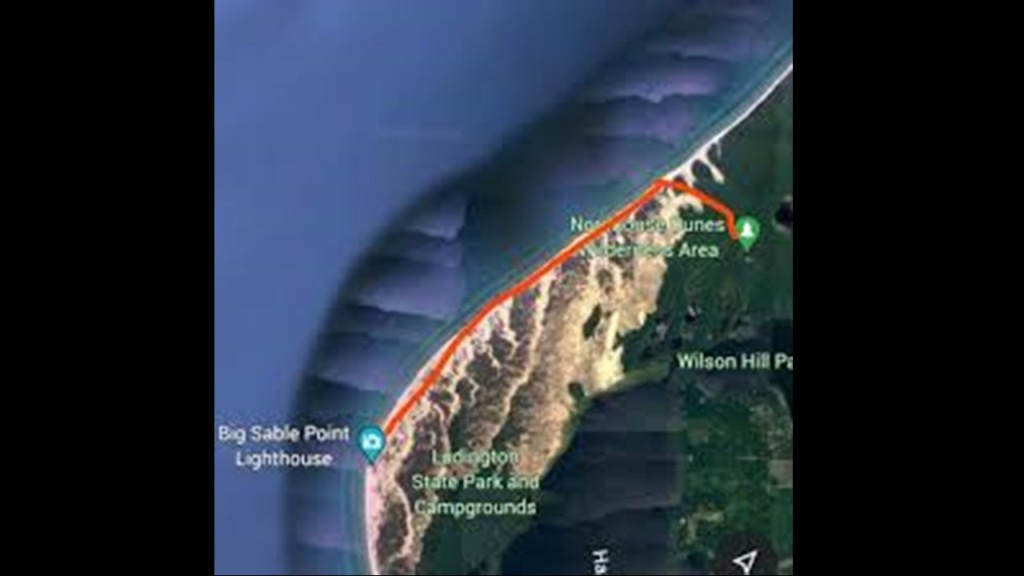

The Big Sable Point Lighthouse is located on the other side of Ludington State Park from the Ludington Lighthouse, in the vicinity of the Nordhouse Dunes Wilderness Area.

The Big Sable Point Lighthouse was said to have been built in 1867, and is just a short-distance north of the Ludington State Park entrance.

We are told that construction materials were brought in by ship since there wasn’t a road to it until 1933, and even today the road to get there is sandy and you have to walk because motor vehicles are prohibited.

Also, this was the last Great Lakes lighthouse to get electricity and plumbing, which came in the late 1940s.

Here it is at sunset as well.

I’ve seen enough lighthouses over the years in perfect alignment with the heavens to more than convince me that in no way are these astronomical alignments occurring randomly but were very much intentional by the original builders and were not built by the people in the historical reset narrative that claimed credit for building them.

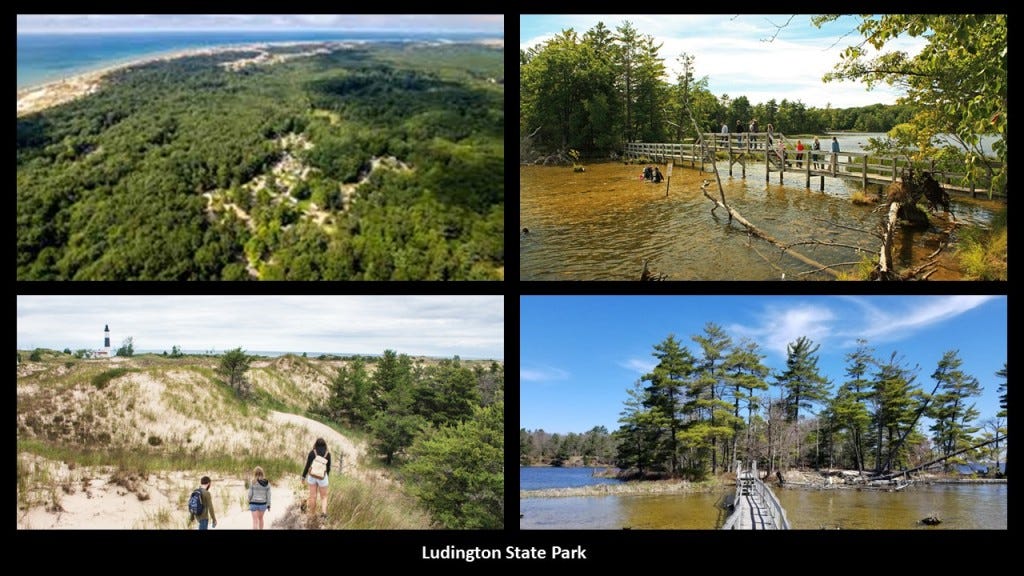

The Ludington State Park, of which the Big Sable Point Lighthouse is a part, is altogether 4,800-acres, or 1,900-hectares in size, with many different kinds of ecosystems, which include sand dunes, wetlands, marshlands and forests.

The Nordhouse Dunes Wilderness Area which is directly adjacent to the Ludington State Park is part of the Manistee National Forest lands, and managed by the U. S. Forest Service.

The federal government declared the Nordhouse Dunes area of the Manistee National Forest a wilderness in the Michigan Wilderness Act of 1987.

On 3,450-acres, or 1,396-hectares of land, it is the world’s most extensive set of freshwater dunes.

Continuing on down the coast a little ways, the next area I am going to look at includes the Silver Lake State Park and the Little Sable Point Lighthouse.

First, Silver Lake State Park.

The Silver Lake State Park is 4-miles, or 6.4-kilometers, west of Mears in Oceana County, and on its almost 3,000-acres, or 1,200-hectares, of land, has along with mature forest land, has over 2,000-acres, or 810-hectares of sand dunes.

We are told that the park originated in 1920, when 25-acres, or 10-hectares, of land for park purposes were donated by Carrie Mears, the daughter of Lumber Baron Charles Mears.

Then in 1926, 900-acres, or 364-hectares, were transferred to the state from the federal government, which became Sand Dunes State Park in 1949.

In 1951, the two parcels of land were merged together to become Silver Lake State Park.

From the limited information available to find on this man, Charles Mears owned huge forests in Michigan, and owned fifteen sawmills.

He was also said to have built cargo boats to move the lumber from the sawmills as well as building several important harbors in western Michigan.

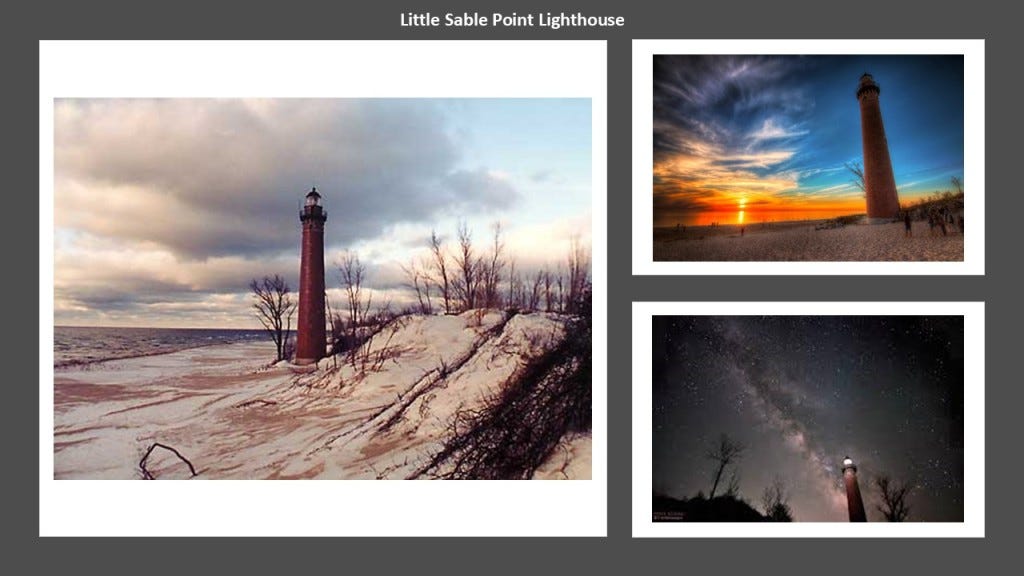

The Little Sable Point Lighthouse is located just south of Silver Lake State Park.

It was said to have been designed by Col. Orlando Poe, and finally constructed in 1874, after funding was approved by Congress in 1871.

Apparently construction was delayed because there weren’t any roads here either according to the official narrative.

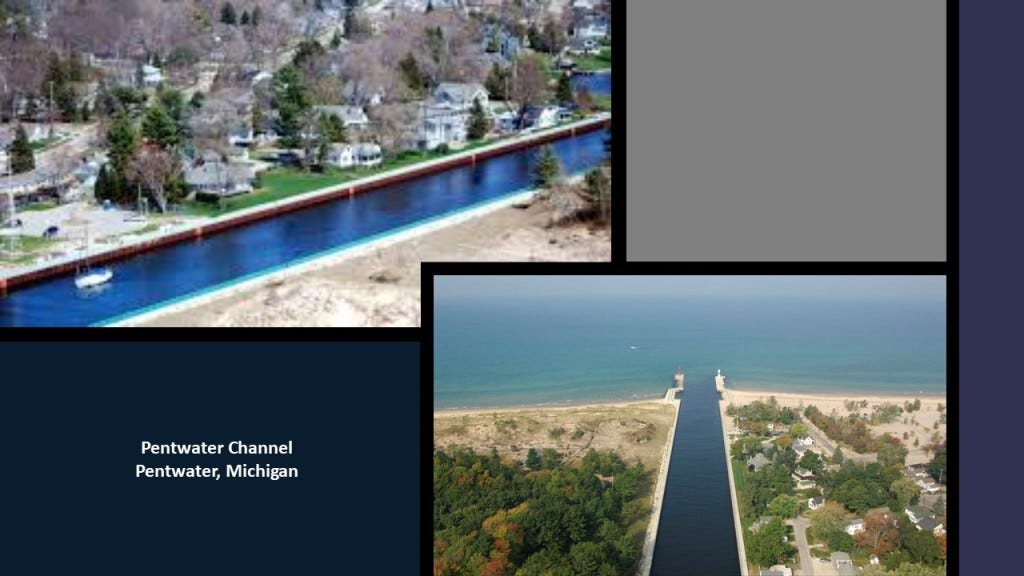

Mears State Park is located north of Silver Lake at Pentwater, which is roughly half-way between the Ludington area and the Silver Lake area.

Mears State Park is comprised of 50-acres, or 20-hectares, of land on the north side of the Channel that connects Pentwater Lake to Lake Michigan, not far from the previously-mentioned Highway 31.

Like Silver Lake State Park, Mears State Park was also said to have come about on land donated to the State in 1920 that was owned by Carrie Mears, and the 16-acres she donated was described as “strictly lake sand,” which was quickly eroded when the vegetation that held it in place was disturbed when the land was graded.

We are told this problem was solved with five-tons of marsh hay that were laid on top of it.

Mears State Park is a swimming, camping, hiking and fishing destination.

Mears State Park is known for its stunning sunsets, like this one behind the Pentwater North Pierhead Light.

Charles Mears was said to have constructed the Pentwater Channel in 1855 to accommodate his lumber interests, and he was said to have constructed a pier here as well, though we are told the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers built the concrete piers we see today in 1937, which would have been during the Great Depression, which lasted from 1929 to 1939.

Interesting to note the presence of megalithic stone blocks in the waters off of Pentwater.

Next, I am going to head down the coast to the Muskegon area, where we also find Hoffmaster State Park and the Gillette Sand Dune Visitor Center and sand dune ecosystem.

First, a little bit about Muskegon, the largest city on Lake Michigan’s eastern shore.

The city of Muskegon is located on the south-side of Muskegon Lake, which is a harbor of Lake Michigan, which like we just saw in Pentwater, is connected to it by a navigational channel.

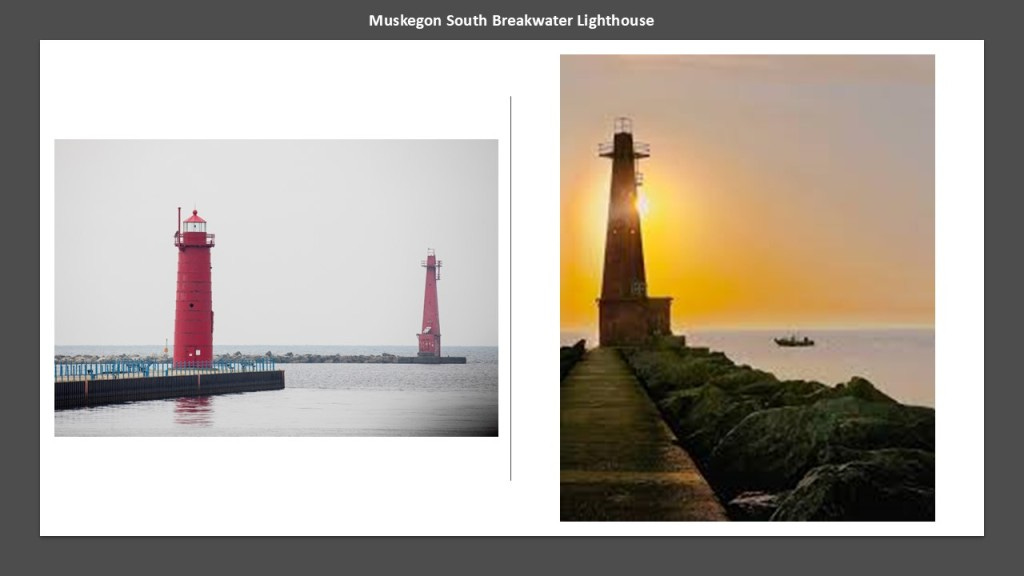

There are two lighthouses at this location – the Muskegon South Pierhead Lighthouse and the Muskegon South Breakwater Lighthouse.

The South Pierhead Lighthouse is located on the Harbor Channel, where there has been said to have been one since 1851, though we are told the current lighthouse was constructed in 1903.

We are told the Muskegon South Breakwater Lighthouse was constructed in 1929 and first lit in 1930.

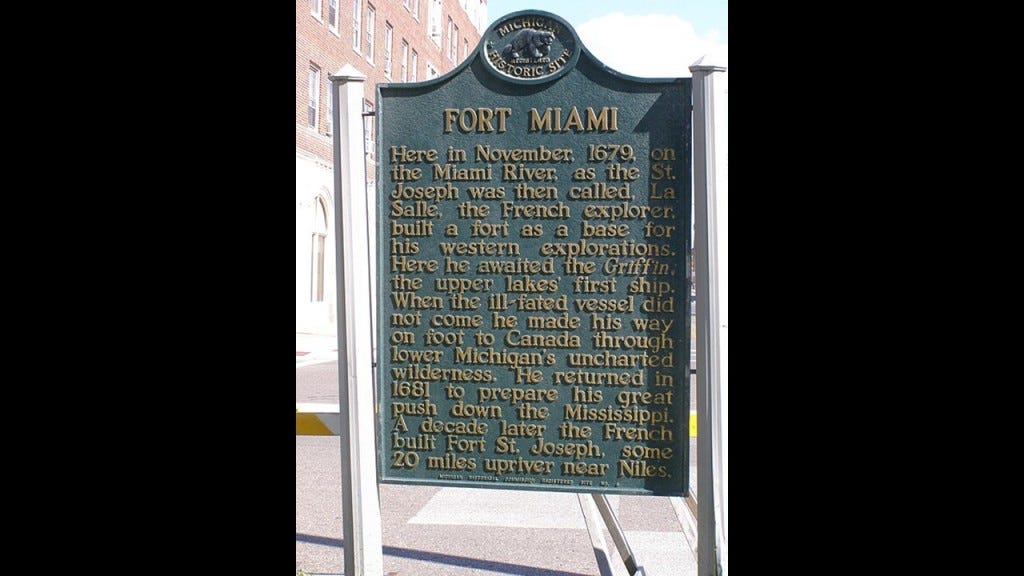

We are told that the earliest Europeans who visited the area were French explorers like the Jesuit Father Marquette and French soldiers under the explorer LaSalle in the late 1670s.

As a matter of fact, Pere Marquette Park is a beach-area that is located just to the south of the south breakwater and pier.

The Pere Marquette quartz-sand beach is bordered by large sand-dunes.

When I was looking for information about Pere Marquette Park, I came across the information that Lake Michigan Park occupied the north end of today’s Pere Marquette Park.

Lake Michigan Park was a trolley park that had a large roller coaster, dance hall, and pavilions where rail service said to have been developed in the late 18th- and early-19th-centuries to encourage local and regional demand.

We are told the trolley park’s closure was linked to the decline of the trolley service, and the amusement park was torn down in 1930, and at some point became Pere Marquette Park.

While the earliest European settlers to the area that became Muskegon were in the fur trade, ultimately the population and economic growth of Muskegon was due to the lumber industry, which began there in 1837, and the city became known as the “Lumber Queen of the World.”

Muskegon also became a manufacturing hub, including but not limited to bowling pins, Raggedy Ann dolls, boats, beer, engines, pianos, and paper to name a few.

This is an historic photograph of Muskegon, circa 1900.

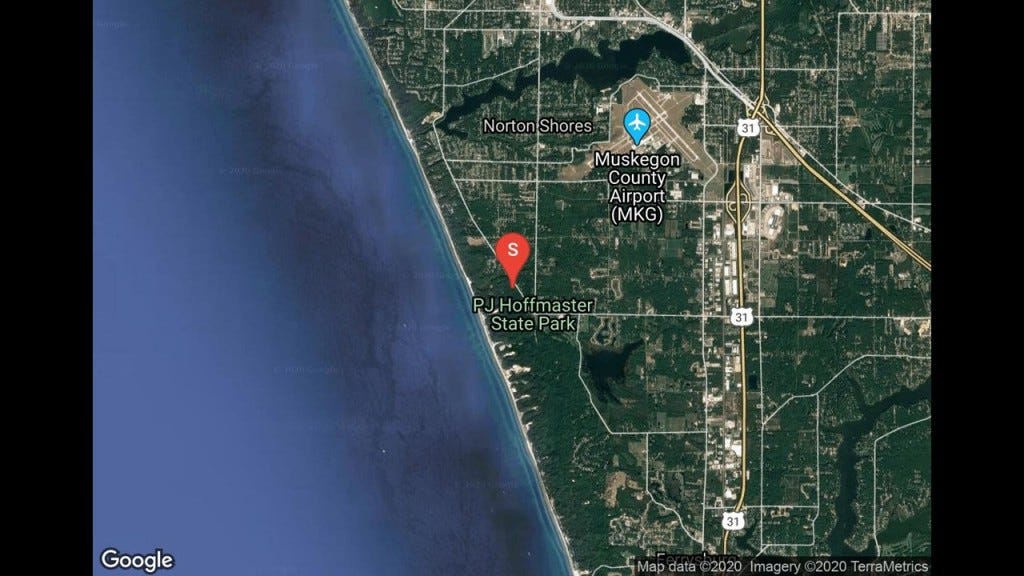

The P. J. Hoffmaster State Park is located south of Norton Shores and the Muskegon County Airport, and just to the west of Highway 31.

It was established in 1963, and named after Percy James Hoffmaster, who was considered the founder of the Michigan State Parks system, and is a public recreation area with hiking trails, camping areas, and a beach.

The Gillette Sand Dune Visitor Center was named after Genevieve Gillette, a conservationist who scouted for new state park locations for P. J. Hoffmaster.

The Gillette Sand Dune Visitor Center is described as being nestled among one of the nation’s most impressive dune systems, and is itself perched on top of a large wooded dune.

Now I am going to head down the eastern coast of Lake Michigan to the Holland area.

Holland is located near the eastern shore of Lake Macatawa, known historically as Black Lake, which is fed by the Macatawa River, known as the Black River.

Historically the landof the Ottawa people, we are told that in 1839, the Reverend George Smith established the Old Wing Mission here as a Christian mission to the Ottawa people, and the building described as a Greek Revival structure is said to be the oldest house in Holland.

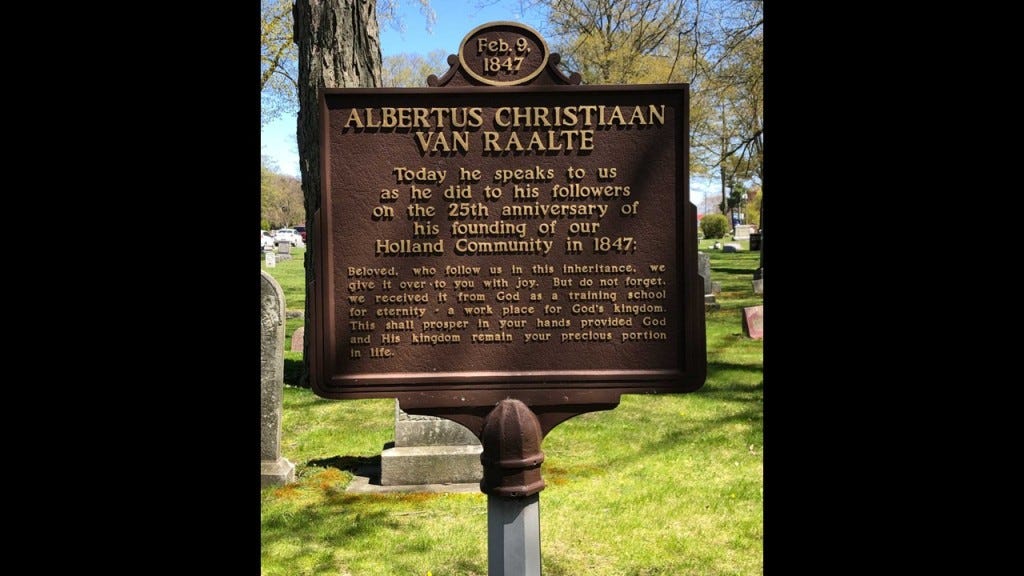

Then we are told in 1847, Holland was settled by Dutch Calvinist Separatists who emigrated from the Netherlands under the leadership of Dr. Albertus van Raalte because of drastic economic conditions there settled in the Old Wing Mission area along with the Ottawa, and there was conflict between the two, resulting in the Ottawa moving north from their land.

Dr. van Raalte then established a congregation of the Reformed Church in America, later called the First Reformed Church of Holland.

Then in 1867, Holland was incorporated as a city.

As I mentioned previously in this post, Holland was one of the locations of the Great Michigan Fire on October 8th of 1871, the same day as the Great Chicago Fire.

The vast majority of downtown Holland burned in the fire, and the cause of the fire remains unknown, though suggested causes have included burning embers from the Chicago fire crossing Lake Michigan, to burning methane gas from a passing comet.

The Holland Harbor Lighthouse is nicknamed “Big Red.”

It is located at the entrance of the channel that connects Lake Macatawa to Lake Michigan, and the current structure was said to have been built in 1907, though we are told a lighthousewas first constructed here in 1872.

The light was automated in 1932 and is maintained by the Coast Guard.

Public access to “Big Red” is limited, so the best viewing location is from across the Harbor at Holland State Park, one of Michigan’s popular beach locations, receiving 1.5-million to 2-million visitors each year.

Another notable place in Holland is Windmill Island Gardens.

This is what we are told about this location.

This is a city park that is home to the 251-year-old De Zwaan Windmill, the only authentic and working Dutch windmill in the United States.

We are told the windmill was purchased from a retired miller in The Netherlands in 1964, and that it was brought over by ship and reconstructed in the park location on artificial island formed by a canal and the Macatawa River and the park opened in 1965.

The park includes 35-acres, or 15-hectares, of land along the Macatawa River and the swamp leading into Lake Macatawa.

Every year, 100,000 tulips bloom in gardens on the island and enjoyed in the summer months, and the Tulip Time Festival every May draws the most crowds.

Here’s the thing.

We’re not being told the truth about traditional wind mills already being here either.

Traditional wind mills were prevalent at one time, and found all over the world.

While some still are in existence, like the lighthouses, their true purpose has been deliberately obscured.

Next, the Saugatuck Dunes state park is located between Holland and Saugatuck.

The Saugatuck Dunes State Park is a largely undeveloped, 1,000-acre, or 400-hectare, public recreation area with a beach, and 14-miles of hiking trails and 200-foot, or 61-meter, -high sand dunes covered with trees and grass.

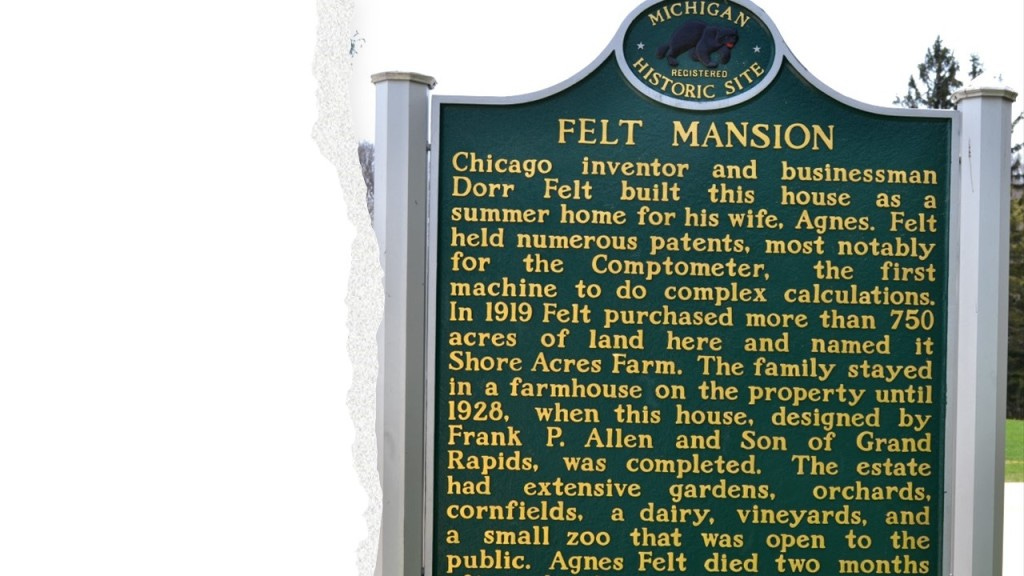

It is interesting to note that the estate of Dorr E. Felt is just to the north of the Saugatuck Dunes State Park.

Dorr E. Felt was known to history as the inventor of the Comptometer, an adding machine and calculator used by businesses.

Apparently, his invention made him a very wealthy man.

So much so, he could afford to build between 1925 and 1928, a 12,000-square-foot, or 1,115-square-meter, mansion, carriage house, farm house, and petting zoo, to be a summer home called “Shore Acres Farm” for he and his wife and children,

Sadly his wife Agnes passed away a couple of months after the family moved into the home, and he only outlived her by a couple of years, and the Felt family finally sold the property in 1949.

The property has also been used as a Catholic Seminary, and also as a prison by the State of Michigan.